Hervé Di Rosa, born in 1959 in Sète on France's Mediterranean coast, has been recognized for over forty years as one of the most active and inventive artists of our time. But, until now, the curators at the Musée National d'Art Moderne were perhaps too busy to take notice. His current retrospective exhibition is the first to be held at the institution – no rush! Furthermore, the space devoted to the show is not particularly generous: a small corner of the fourth floor, nothing more. In 2016, Antoine de Galbert's Maison Rouge gave him a warm welcome in Paris, and numerous museums and galleries, in France and elsewhere, have long displayed him, maintaining his renown. This makes the slimness of the exhibition granted by the Centre Pompidou all the more noticeable and unfortunate.

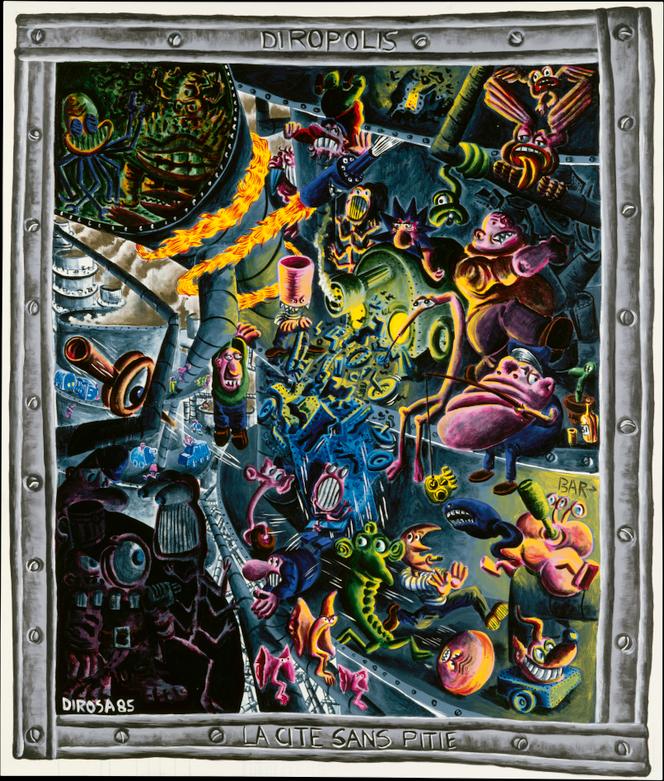

It's true that Hervé Di Rosa has had a fraught relationship with the museum establishment, on three occasions challenging its doctrines and certainties. The first of these was when he initially appeared on the scene in the early 1980s. At a time when it seemed to be common knowledge in specialized French art circles (which is to say, at the Centre Pompidou) that contemporary art had to be at least minimal, if not conceptual, and that painting was irredeemably old-fashioned – an opinion not shared in Germany, the US or Italy – Di Rosa began showing paintings. They were large, agitated, figurative, brightly colored and sharply drawn, and depicted themes from science fiction. Robots, monsters, interstellar battles: think Star Wars, but in comic-book style, and in large format, with a very sure sense of composition.

They caught the eye of Suzanne Pagé, then director of the contemporary art department of the experimental Animation Recherche Confrontation (ARC) section at the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, who exhibited them in 1982, and of critic Bernard Lamarche-Vadel. Along with Rémi Blanchard, François Boisrond and Robert Combas, Di Rosa then formed the "figuration libre" quartet, whose New York contemporaries and counterparts were artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring. So, in 1984, American and French artists put up an exhibit together at the ARC. It wasn't minimal, elliptical or ascetic, but brutal, satirical and politically engaged, going against the grain of official thinking. In retrospect, this invasion appears as one of the first signs of the crisis of the abstract modernist system, which has since collapsed. Di Rosa's recent paintings, which conclude the visit, still have this critical energy: He disrupts codes, daring to combine, for example, gold monochrome with grotesque cyclops heads, playing on the various uses of gold, from religious iconography to stock market investments.

You have 45.92% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.