A fairground atmosphere reigned in the sun-drenched courtyard of the special labor court in Port-au-Prince, the Haitian capital. Sellers of law books had set up their second-hand wares on a low wall in a shady corner of the courtyard. Unknown people approached visitors and offered their legal expertise. At the far end, in a small, plain, unattractive building, civil servants in suits and ties crammed into tiny, sparsely furnished rooms. "Our public prosecutor's office is in shambles," said Lionel Constant Bourgoin, Port-au-Prince's government commissioner – a position equivalent to that of prosecutor. "The gangs have driven the magistrates out of their courts."

This situation has persisted since the courthouse in the Bicentenaire district was ransacked by armed bandits from the nearby Village-de-Dieu shantytown in June 2022. Like these downtown areas, 80% of Port-au-Prince is controlled by gangs who terrorize the population with impunity. "Many case files remain at the Bicentenaire," lamented the magistrate from the Prosecutor's Office.

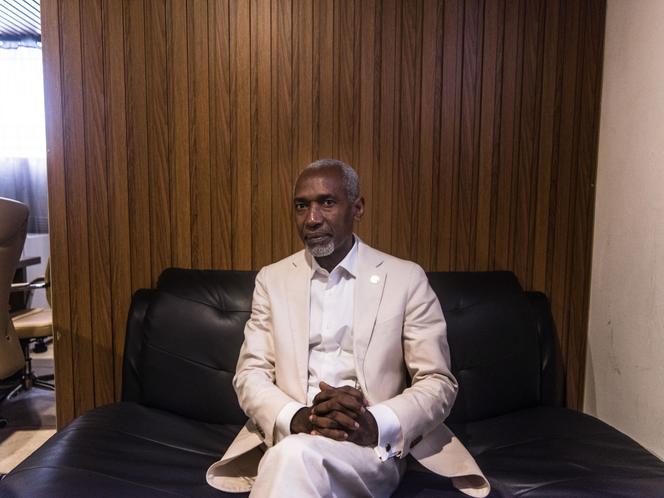

Since the attack, the Port-au-Prince trial court, the largest of the country's 18 courts, has been housed in these premises, which it shares with the special labor court. The two operate on an alternate schedule: two days a week for the labor court, on Tuesdays and Thursdays, and the other three days for the trial court and the prosecutor’s office. "Twenty-two people take turns sharing these offices," explained Bourgoin as he left a room with no windows or air-conditioning. "This has an impact on their judicial output, and on the safety of the magistrates."

Lacking sufficient funding, working conditions in Haiti's courts are unlikely to improve any time soon. "Justice represents around 1% of the government budget," said Marthel Jean-Claude, the president of the Professional Association of Magistrates (APM). This budget is "used solely for the payment of civil servants," continued the trial court judge, who is calling for investments to renovate "inadequate" premises and for resources to conduct investigations. To make matters worse, repeated strikes by court clerks, lawyers and magistrates, angry at their "appalling" working conditions, are further paralyzing the institution. "Investigations can't be brought to a conclusion," said Jean-Claude. "In the metropolitan region [of Port-au-Prince], justice is virtually dysfunctional."

As a result, gang crimes go unpunished and the re-establishment of the rule of law is a distant hope in this Caribbean country beset by a political and security crisis that has been steadily worsening for several years. "The La Saline massacre was never punished by the justice system," said Rosy Auguste Ducéna, program manager at the National Human Rights Defense Network NGO, referring to a massacre that left 71 people dead in a shantytown in the capital in November 2018, after a demonstration against the government. Since that first bloodbath, "we are now at 30 massacres [with more than ten victims] and armed attacks in Haiti," said this lawyer at the Port-au-Prince bar. To date, no gang leader has been arrested in this country, which has almost 200 armed groups. The paralysis of justice is such that the last trial before the Assize Court in Port-au-Prince was held in July 2018.

You have 37.39% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.