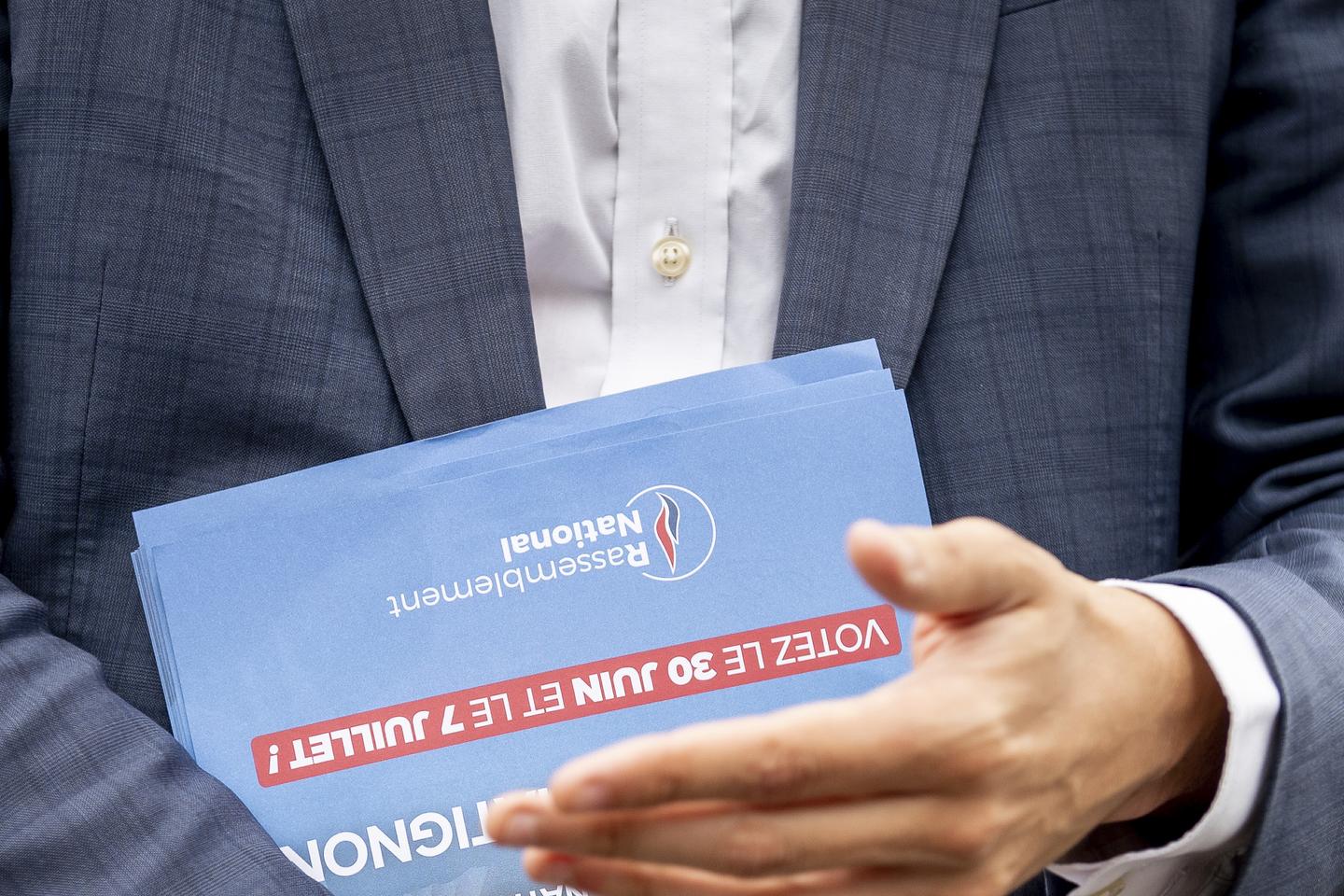

When President Emmanuel Macron declared the dissolution of the Assemblée Nationale on June 9, all the Rassemblement National (RN) had to do was "press the button" to trigger its "Matignon plan," named after the residence of France's prime minister. Or so the far-right party's leaders claimed. For two years, the RN had been preparing for a return to the polls, fielding its future candidates and fine-tuning their policy platform. For two years, this strategy occupied time and minds.

How do they explain the January shutdown of Campus Héméra, the party's leadership school? "We need to give priority to training members for the dissolution," justified RN president Jordan Bardella. The fact that Saidali Boina Hamissi was maintained as departmental delegate in the overseas territory of Mayotte, despite racist and conspiratorial remarks? "We'll deal with the reorganization of the party later, now is the time for nominations for future legislative elections," he said, brushing the issue aside.

Macron announced the dissolution and the "Matignon plan" was unleashed, with, in its wake, the nomination of dozens of racist, anti-Semitic, xenophobic candidates; former members of violent nationalist organizations; and people who had been convicted by the courts. They are mere "black sheep," in the words of Bardella, who maintained against the evidence that "in 99.9% of cases, there are absolutely no difficulties." The MEP refuses to admit that, while he was sometimes alone in betting on a dissolution, his alleged foresight failed to enable his party to "stand ready," as he had promised in November 2022 after becoming president of the former National Front (FN).

With just a few days to go before the second round of snap parliamentary elections on Sunday, July 7, the leaders of the party are now hoping that many of the radical candidates pinpointed by the press will not get elected. "The success of our 'Matigon plan' will be measured by the quality of the group that emerges from the ballot box," Philippe Olivier, RN leader Marine Le Pen's main adviser and front-line operative, told Le Monde.

Imprecise decision-making

In his desire to "build a new popular elite, like the Parti Communiste in its day, people who were not predestined for politics," Olivier called for tolerance for "these things that are part of life, made up of cracks and rough edges." As a member of the National Nomination Commission (CNI), which he said was responsible for approving five candidacies a week for early legislative elections that were only hypothetical at the time, Olivier maintained that the RN just "let a few individuals slip through the net." But he remained sympathetic to those who have since been excluded.

You have 53.67% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.