The French flag gently swayed under a gray, threatening sky, like the silence before a storm. Then the Choir of the French Army launched into the song "Les commandos d'Afrique" ("The Commandos of Africa"). On either side of the central path that runs down the middle of the marine cemetery are tombs as far as the eye can see, amid pine and white laurel trees. At the entrance to the Estérel forest, 5 kilometers from the center of Saint-Raphaël (Var), the Boulouris-sur-Mer international cemetery is home to the graves of 464 French soldiers of all origins and denominations, who died on the sidelines of the Provence landings on August 15, 1944. Each grave bears the name of a "hero," his unit, rank and religion, the date of death and the words "Died for France."

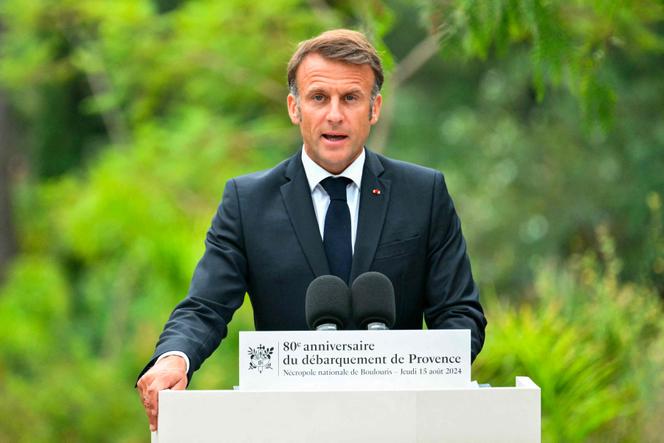

This place of remembrance, striking for its natural beauty, was inaugurated by General de Gaulle in 1964. Sixty years later, it was French President Emmanuel Macron who stood here, on Thursday, August 15, in front of a handful of veterans, for the 80th anniversary of the Provence landings. The landing of 100,000 American, Canadian and British troops on August 15, 1944, was largely overshadowed by the D-Day invasion of Normandy, but it was a little-known − and sometimes, even forgotten − event that hastened the victory over Nazi Germany, cornering the occupying forces and precipitating their collapse.

Initially named "Anvil," the carefully prepared operation was eventually dubbed "Anvil-Dragoon" by Churchill, who was not in favor of it. The Allied landing paved the way for more than 250,000 French members of the "B Army": Under the command of General de Lattre de Tassigny, they were able to retake Toulon and Marseille in less than two weeks, and at least partially wipe away the humiliation of 1940.

Mainly made up of troops from the French colonies in Africa, this future "First Army" included 84,000 French nationals from North Africa, 12,000 soldiers from the Free French Forces (FFL) loyal to de Gaulle and 12,000 Corsicans, as well as 130,000 so-called "Muslim" soldiers from Algeria and Morocco and 12,000 soldiers from the colonial army, such as Senegalese tirailleurs (indigenous French army colonial-era troops) and marsouins (indigenous naval forces) from the Pacific and the West Indies.

"These men were called François, Boudjema, Harry, Pierre, Niakara," said Macron, recalling that "many of them − spahis [native light-cavalry regiments], goumiers [native soldiers], African tirailleurs, West Indians, Pacific marsouins − had never set foot on French soil" before being sent to help liberate France. "Officers of the empire or children of the Sahara, natives of Casamance or Madagascar, (...) they were not of the same generation, they were not of the same faith, (...) yet they were the army of the nation, the most fervent and most colorful army," he said emphatically.

You have 59.15% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.