Forty years ago, the West discovered the images of the great Ethiopian famine

Long ReadEthiopia is once again on the brink of famine, forty years after the disaster that claimed the lives of over 300,000 people in 1984.

"There are no longer any natural famines in the world; there are only political famines. If people in Syria, Sudan or Somalia starve to death, it's because some politician wants them to," writes academic and historian Yuval Noah Harari in his book Homo Deus. His assertion finds particular resonance today in the humanitarian situations in Gaza, where famine is "imminent" according to the United Nations; in Sudan, where civil war has plunged 18 million people into an unprecedented hunger crisis and northern Ethiopia, where the specter of famine is resurfacing after the devastation left by the Tigray conflict (2020-2022).

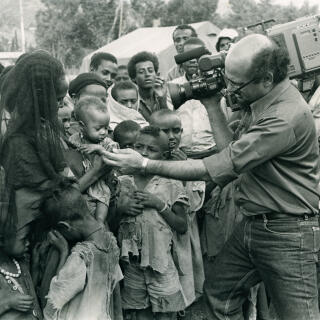

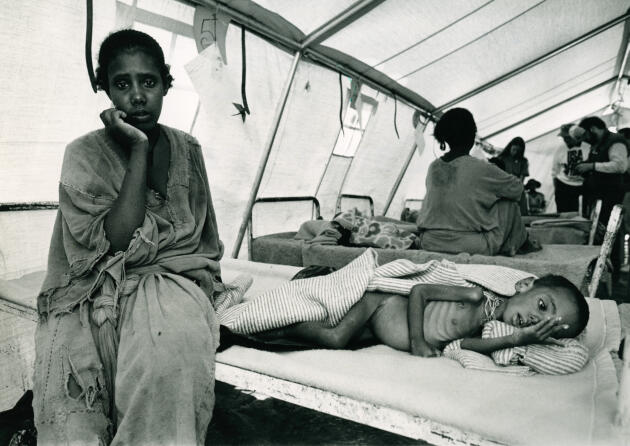

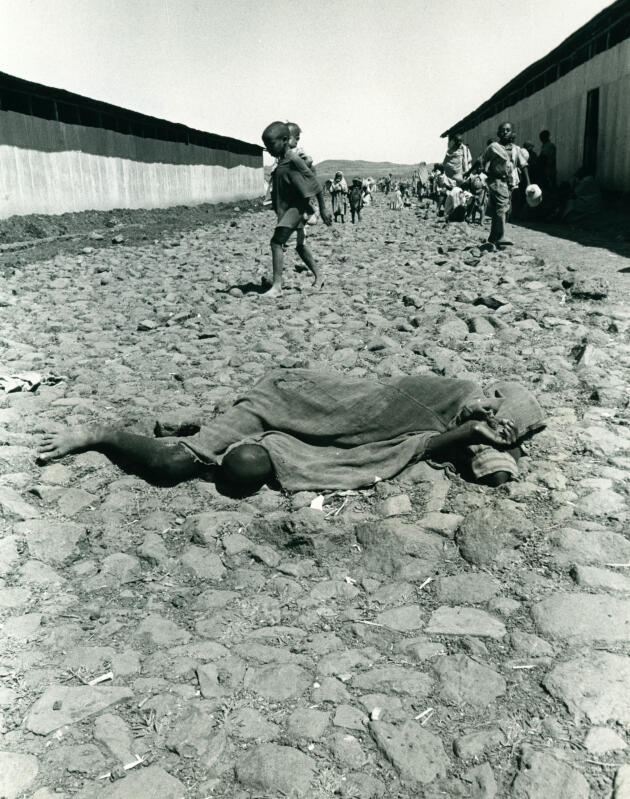

Forty years earlier, it was from these same Ethiopian provinces of Tigray and Wollo that apocalyptic images emerged of a devastating famine that claimed more than 300,000 lives. Photographs of men and women on the verge of starving to death in front of the lens of journalists were seen around the world, shocking the West and giving rise to an unprecedented wave of solidarity, the most visible manifestations of which were recorded by the musical elite in the US, UK and France.

The famine of 1984 reached "biblical proportions," in the words of BBC reporter Michael Buerk, as he commented on his report from an arid, cold Wollo valley, transformed into an immense open-air camp where hundreds of displaced people, fleeing civil war and hunger, died every night and whose bodies were picked up by truckloads in the early hours of the morning. He was accompanied by Kenyan photographer Mohamed Amin, whose photo archives are published here.

A formidable weapon

These images are still very much a part of Ethiopia today. The country's northern highlands experience droughts of varying severity roughly every decade. Ten years earlier, in 1973, the lack of rain killed some 50,000 farmers in the area, under the indifferent gaze of Emperor Haile Selassie I, who had even been quick to cover it up, at the risk of tarnishing his reputation. Public anger, fueled by a Marxist student revolution that used the Wollo famine to illustrate the monarch's selfishness and cruelty, precipitated his downfall the following year, 1974.

As Harari suggests, hunger can be a formidable weapon in war, and Ethiopia is no exception. While the land in the north of the country is vulnerable to drought, food crises there have always been aggravated by revolts and their repression. Current events are a painful reminder of this. During the Tigray War (2020-2022), a blockade put in place by the government of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed – winner of the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize – prevented humanitarian aid from arriving and pushed 90% of Tigray to the brink of famine. Today, a year and a half after the peace agreement that ended the conflict, hunger is still killing. In the last six months, 1,390 Tigrayans died from it, according to regional authorities.

You have 61.02% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.