If the Rassemblement National (RN) came out on top on Sunday, June 9, and hopes to further strengthen its electoral success in the early legislative elections, women had something to do with it, and that raises questions. Between the 2019 and 2024 European elections, Marine Le Pen's party gained 10 points among the female electorate, rising from 20% to 30% (Ipsos). Another poll (IFOP) even puts the figure as high as 32%, putting them ahead of men.

The gender gap, that long-observed difference between male and female electoral behavior, is well and truly over. In France, political scientists have identified four periods. The first three were: the learning period, from 1944 to the 1970s, when women voted less than men and tended to opt for the right – for example, 61% of women voted for President Charles de Gaulle in 1965; the stabilization period, from the 1970s to the mid-1980s, when women's and men's political participation and orientation became more similar; the inversion period, since the late 1980s, when women participated more than men and made more progressive political choices – for example, it was women who ensured President François Mitterrand's re-election in 1988, giving him 51% of their votes against 47% for men.

A common thread running through all these decades is the rejection of the far right: the radical right gender gap, theorized by African-American researcher Terri E. Givens in 2005. Taking all elections into account, the average gap between French women's and men's voting levels for the RN's predecessor, the Front National (FN), was four points between 1984 and 2002. On April 21, 2002, Jean-Marie Le Pen won 26% of the male vote against just 11% of the female vote. If only women had voted that day, the far-right leader would not have been present in the second round of the presidential election. Anti-Lepenism is therefore at its highest among young, educated women, on the one hand, and older, Catholic women voters, on the other.

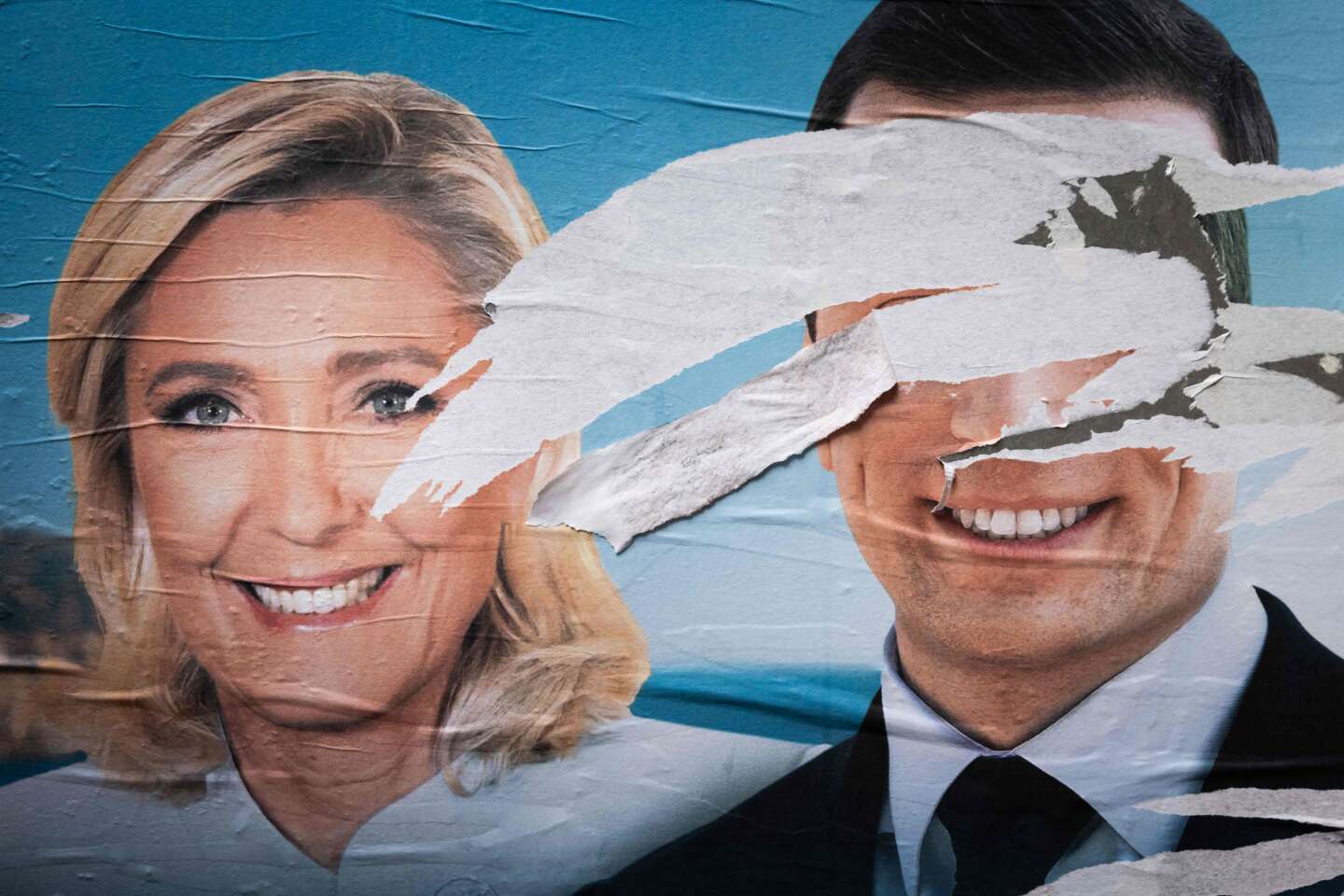

'Marine effect'

As political scientist and sociologist Mariette Sineau has shown, women's reluctance to vote for the FN has sometimes been explained by a psychological (and essentializing) argument: The socialization of girls, educated to obedience and concern for others, would explain why they are more reluctant, as adults, to vote for extremes. More often, the socio-economic argument has been put forward: Women are more precarious, are the main beneficiaries of social benefits and, consequently, are more favorable to the parties that support them. Added to this is the idea that these same parties are also those most open to feminist themes and struggles.

You have 53.45% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.