The few researchers who went through the grievances written during the winter of 2018-2019, at the height of the Yellow Vest crisis, are unanimous. "This is valuable material that deserves to be better utilized to inform public debate," said Manon Pengam, a lecturer in language sciences at CY Cergy-Paris University. Samuel Noguera, a doctoral student at the Centre Emile-Durkheim at Sciences Po Bordeaux, who is preparing a thesis on the list of grievances in Gironde in southern France, agreed. "This is an unprecedented space for expression." The documents reflect a quest for dignity and territorial and fiscal justice, difficulties accessing healthcare and public services, and feelings of isolation.

Five years on, the demands and proposals put forward by the French people – many living in rural areas – have lost none of their relevance. Meanwhile, crisis after crisis has followed.

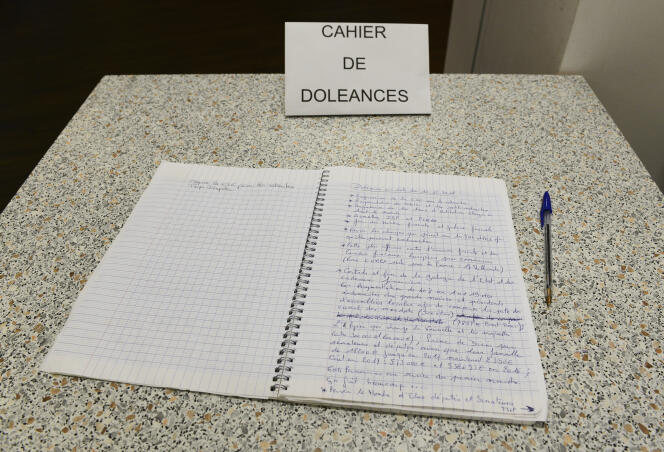

In January 2019, seeking a way out of the Yellow Vest crisis that was blocking the nation's roundabouts, President Emmanuel Macron launched a Great National Debate. This meant him sounding out the French via roadshows, an online platform, and with the cahiers de doléances, or notebooks in which to list grievances, that were placed in French town halls. The latter mode of consultation was particularly popular. There were 19,899 such notebooks, containing over 200,000 handwritten grievances across some 16,500 town halls. Above all, "the cahiers engaged a more rural, older and less politicized population, to whom we don't usually have access," said Noguera.

The president was due to present these grievances on April 15, 2019, but the fire at Notre Dame de Paris decided otherwise. The conclusion of the Great Debate never took place.

As for the notebooks, almost all of them have been digitized, transcribed and preserved in France's National Archives in digital format. They were consolidated by private operators in June 2019, before returning to rest on the shelves of departmental archives. The cahiers de doléances, which bear the name of the lists of grievances drawn up by the Three Estates at the start of the French Revolution, were classified according to two categories: those that can be consulted and those that will not be consulted for 50 years, as they contain sensitive information relating to the private lives of the authors (postal, telephone, bank details), unless a request for a prefectural dispensation is made.

Make no mistake, however, "the notebooks were not confiscated," stressed Magali Della Sudda, a political science researcher at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) and member of a citizen research collective in Gironde. "They were simply ignored, hence the fact that they are under-utilized, including by researchers." And yet, they contain a wealth of information that showcases the expectations of the French people.

You have 70% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.