Fired for being Jewish, executed for being a resistant: Marc Bloch's WWII years

From the ArchiveFrench President Emmanuel Macron announced on November 23, 2024, that Marc Bloch would be inducted into the Panthéon, alongside other great national figures. This article, originally published in February 2024, recounts the historian's journey through the Second World War, which he didn't survive.

In his notebooks, he jotted down this line from Corneille: "I never hated life, or wooed a grave / To life I am a servant – not a slave" (Polyeucte, V, II). In October 1940, Marc Bloch was reflecting on life, war and history at his home, a beautiful house with burgundy shutters and a large garden in Fougères, a hamlet of Bourg-d'Hem in central France. The great historian was 54, had six children and was suffering from painful polyarthritis. He had just put the finishing touches to his book L'Etrange Défaite (Strange Defeat), a major historical work that would not be published until 1946, after the Liberation and after Bloch's execution by the Gestapo.

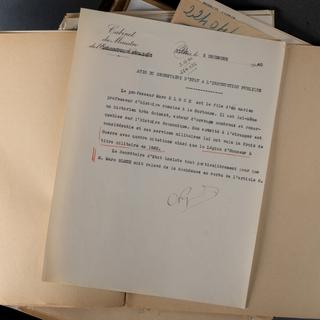

Bloch was well known by then. He had been a professor of history at the Sorbonne since 1936 and had held the chair of economic history since two years after that. He founded the Annales school of history with Lucien Febvre. But the first law on the status of Jews, passed by the Vichy collaborationist regime on October 3, 1940, cut his career short: Bloch was fired, as were almost 3,000 Jews, around a third of whom were teachers and professors like him.

"By birth I am a Jew," wrote Bloch in Strange Defeat, "though not by religion, for I have never professed any creed, whether Hebrew or Christian. I feel neither pride nor shame in my origins. I am, I hope, a sufficiently good historian to know that racial qualities are a myth, and that the whole notion of Race is an absurdity (...) I am at pains never to stress my heredity save when I find myself in the presence of an anti-Semite."

He added a beautiful page: "France, from which many would like to expel me to-day (and may, for all I know, succeed in doing so), will remain, whatever happens, the one country with which my deepest emotions are inextricably bound up. I was born in France. I have drunk of the waters of her culture. I have made her past my own. I breathe freely only in her climate, and I have done my best, with others, to defend her interests."

Teaching and research were his life. His father, Gustave, was already a respected professor of Roman history at the Sorbonne and young Marc followed in his footsteps: at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand in Paris, where he excelled – the principal noted on his booklet: "A first-rate student, with a firmness of judgment, a distinction and a curiosity of mind that are truly remarkable" – he collected prizes, every year and in every subject. The young man entered the Ecole Normale Supérieure (ENS) in 1904, where his strict father taught.

You have 89.02% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.