When it comes to immigration, European governments are juggling paradoxes. While illegal crossings of the European Union's external borders (380,000 in 2023, +17%) and asylum applications (806,000 from January to September 2023, +22%) are at their highest since 2015–2016, the 27 member states have adopted a raft of restrictive measures. Meanwhile in the UK, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak is trying to deter arrivals across the Channel by transferring asylum seekers to Rwanda.

Yet, at the same time, Europe's aging population is short of manpower. By the end of 2023, three-quarters of the continent's SMEs reported unsuccessful searches for personnel. Moreover, the trend is set to continue. According to Ylva Johansson, EU Home Affairs Commissioner, over the next six years, some 7 million workers will leave the job market. Business organizations in many countries are calling for solutions.

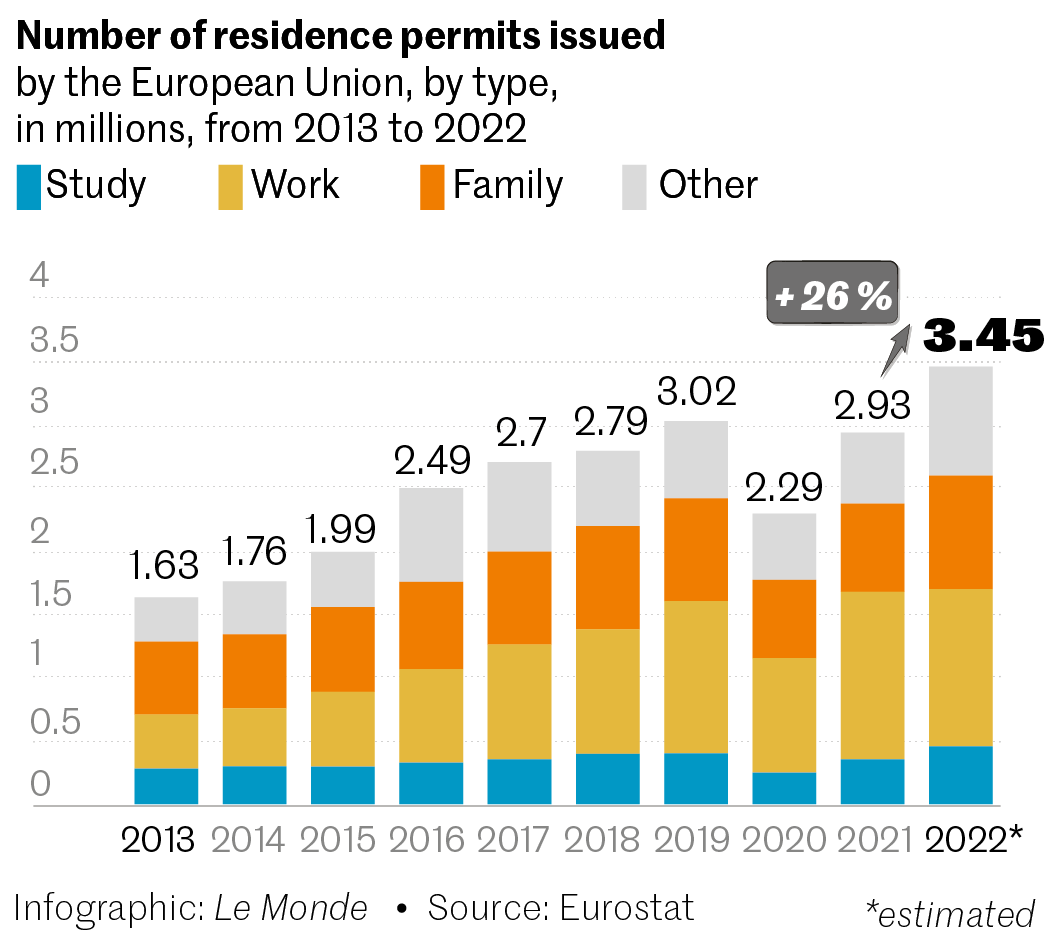

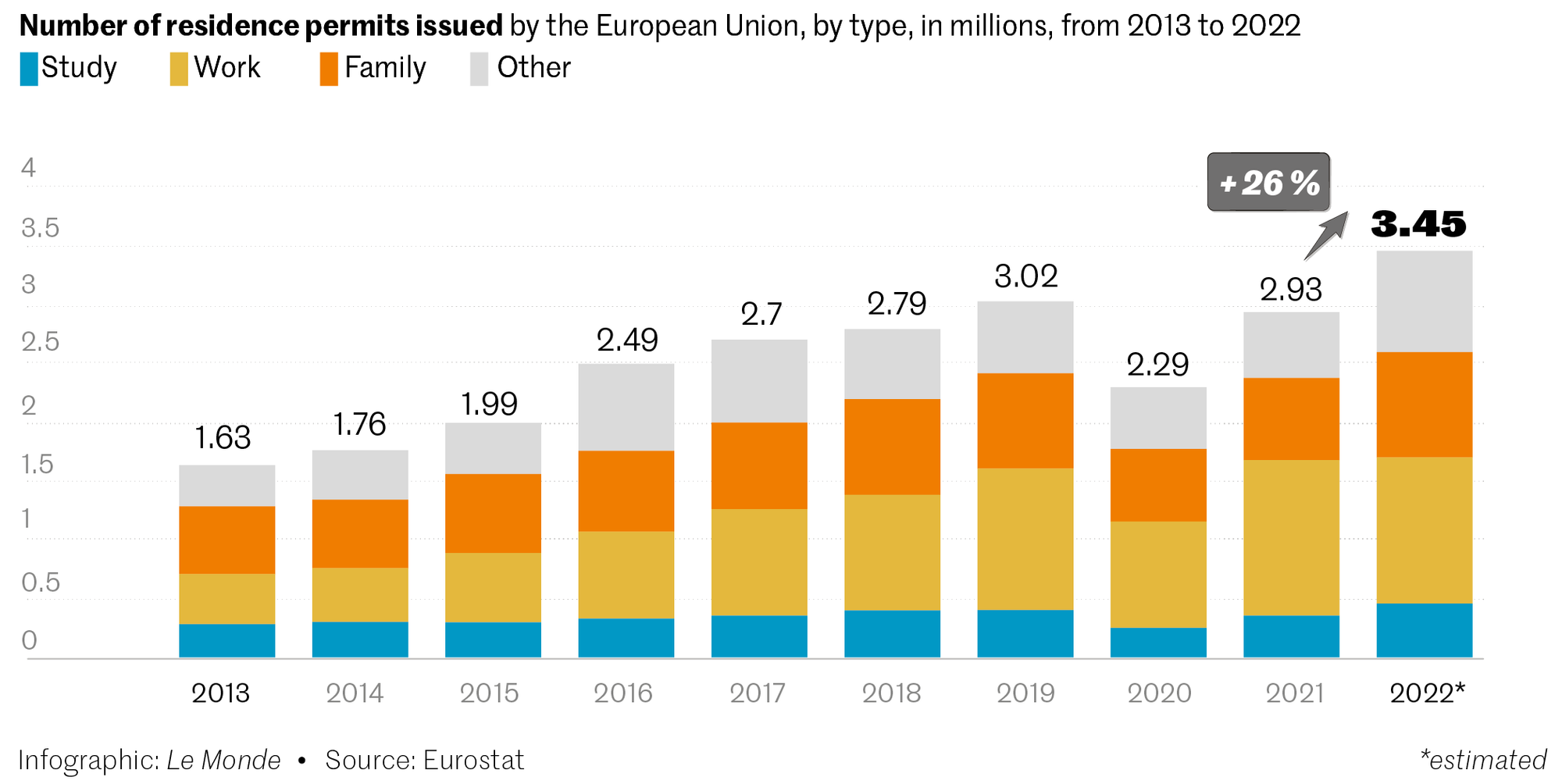

Given the needs, legal immigration at current levels remains insufficient. According to the Commission's vice president for "Promoting our European Way of Life," Margaritis Schinas, in 2023, of the 3.5 million people who entered Europe legally, only 1.2 million had a work visa. In order to prevent many people from taking to the sea and risking their lives by coming to Europe, they need a much safer path by developing ways of entering legally, such as by getting a work visa, argues Johansson.

Pressured by various industries, governments of all political leanings – including those most hostile to immigration – have recently modified their legislation to offset labor shortages. Some have set up "selective" immigration channels, signing agreements where necessary with countries that are often not the main sources of migrants knocking on the EU's door.

In 2015, Viktor Orban plastered Hungary with posters proclaiming that he would never let foreigners "take Hungarians' jobs." Nine years later, in early 2024, Hungarians were shocked to learn that a Korean automotive equipment factory in the north of the country had decided to lay off around 40 Hungarian workers and replace them with "guest workers," in particular from Vietnam.

"It is only possible to employ a non-Hungarian worker if no Hungarian is available to fill the position," government spokesperson Gergely Gulyas responded on January 18, promising an investigation into the company. However, the incident is a result of the abrupt political shift made by Orban's nationalist government from 2022 onward. After years of fierce opposition to all forms of immigration, it suddenly opened the country's doors to tens of thousands of foreign workers to meet employers' needs in a country experiencing full employment.

You have 80% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.