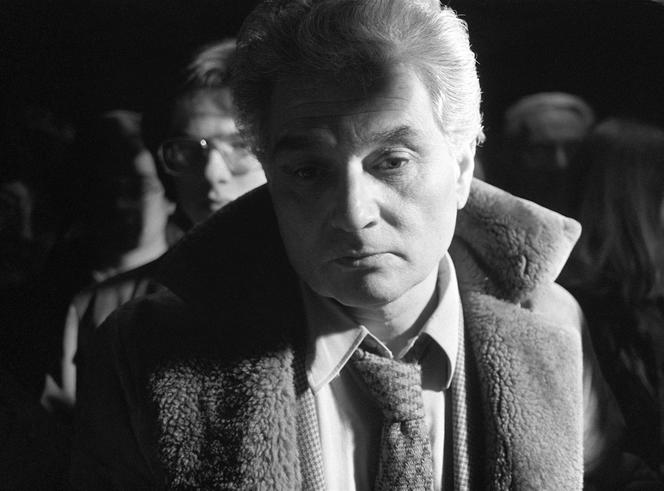

In 2010, writer and essayist Benoît Peeters published Derrida: A Biography, the philosopher's first biography. In an interview with Le Monde's book section, he discussed the influence and place of Derrida's thought in today's philosophically evolving context. He also reflected on the posterity of a work that is often hard to find in bookshops, owing to a publishing environment that has long been alarming.

First, let's avoid confining it to his French and North American readings. In Latin America, Spain and even Asia, he is very present. His reception today is global. In the United States, one is well aware that fashions come and go, and that, after a somewhat staggering vogue of French Theory and Derridism in universities, other thinkers have taken their places. Interest in and curiosity about Derrida's work certainly remain high, but the immense and strange Derridean wave has subsided somewhat. In France, this reception suffers from a simplistic use of the term "deconstruction," which already infuriated Derrida. Deconstruction is transformed into a form of nihilism, a questioning of all and nothing. It is forgotten that, for Derrida, deconstruction meant first and foremost a genealogy, a patient and fine reading, and not this crude concept used indiscriminately, or even evoked polemically as the cause of all our ills, of everything that goes wrong.

The Heideggerian question is indeed a factor that could "weigh down" this reception. His book of support, Heidegger: The Question of Being and History [1987], and his defense of Heidegger had a contrived character for which he can be criticized. The finesse of Derrida's reading prevented him, in this instance, from clearly stating what had been Heidegger's allegiance to Nazism. I believe, however, that Derrida's debt to the German philosopher diminished as his work progressed. From the late 1980s onwards, political, ethical and religious questions took on an increasingly important role. This seems to be a direct response to his critics. Derrida did not like it to be referred to as a "turning point," but in reality, when we look at the seminar on the question of responsibility [Répondre - du secret ("Respond – On Secrecy") Seminar 1991-1992, 2024], we see that his thinking detached itself from a very ancient Heideggerian trace, specific to his own generation. The meetings that many had wanted to organize between the old Heidegger and Derrida never took place, and Derrida felt that this was no accident.

You have 47.13% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.