D-Day landings: The living history buried in the Normandy American Cemetery

Long ReadThe 9,388 white marble headstones tell the great story of D-Day in their own way, as well as the more personal stories of the men and women who lost their lives.

There's one place that most Americans visiting France for the first time wouldn't miss for the world. A place they put at the top of their bucket list, ahead of the Eiffel Tower or Mont Saint-Michel. A singular location with no admission fees or shops; a place whose beauty vies with its solemnity, its emotion with its serenity, as well as a touch of sadness. One might have imagined that its appeal would fade with the years since the Second World War, that family visits would have grown sparse until they slowly died out. In fact, the opposite has happened: The American cemetery in the Normandy commune of Colleville-sur-Mer has never been so popular since it was solemnly opened in 1956. Nearly 2 million visitors are expected this year. Major commemorations, such as the 80th anniversary of the Normandy landings, only add to its aura.

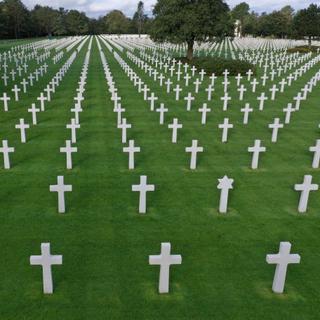

Facing the sea, overlooking Omaha beach, 9,388 white Lasa marble headstones stand in perfect alignment on a manicured lawn tended by some 20 gardeners. There is no hierarchy between the tombs; generals and conscripts lie side by side. On the Latin crosses or Stars of David are simply etched their name, rank, fighting unit, state of enlistment, official date of death and military identity plate number. Their age is not mentioned so that the death of a very young man cannot be pitied more than that of a great elder. All that is known is that the average age of those buried here was 22. Most perished during the D-Day landings.

The question of how to bury fallen soldiers arose on the evening of June 6, 1944, when over 10,000 Allied casualties were recorded. On the morning of June 7, the American army created a makeshift cemetery on Omaha Beach, at the foot of the cliffs between Vierville-sur-Mer and Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer. They had to act quickly, given the growing number of casualties. The process was entrusted to the American Graves Registration Service, including planning ahead, identifying sites and renting land on which to set up temporary cemeteries in a hurry. A dozen such cemeteries were created in Normandy as the army advanced, depending on the intensity of the fighting and the location of field hospitals. After the war, however, the Americans sought to create a great cemetery for the Battle of Normandy. In 1947, France offered its liberators a 70-hectare site overlooking Omaha Beach.

The use of this plot of land was granted to the US in perpetuity, as is customary for all military cemeteries connected to the two world wars and where French law applies. It is managed by the American Battle Monuments Commission, a government agency responsible for its design, hiring engineers, architects, sculptors and landscapers. This agency gradually transferred the bodies from the various makeshift cemeteries. "It took years," said Scott Desjardins, the cemetery's superintendent, "so punctilious was the administration in identifying the bodies and reporting the circumstances of death and burial. Some soldiers had already been buried up to five times."

You have 85.28% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.