Where can we find the trillions of dollars needed for ecological transition, particularly in developing countries? And how can we ensure that polluters pay for their damage? It was to answer these questions that a working group on solidarity taxes was launched in 2023, led by France, Kenya and Barbados. It delivered its first guidelines, on Thursday, November 14, drawing up a list of possible taxes – and expected revenues – on fossil fuels, air and sea transport, financial transactions and even plastic, cryptocurrencies and the super-rich, a financing and equity issue at the heart of the 29th Conference of the Parties on Climate Change (COP29), taking place in Baku.

"Current public financial commitments aren't enough, so we need to consider taxes," Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley said from the COP29 podium on Tuesday, taking aim at high-emissions sectors that are getting rich without doing their fair share of the global climate effort. "Between shipping, aviation and fossil fuels, we're easily around $350 billion a year," she said.

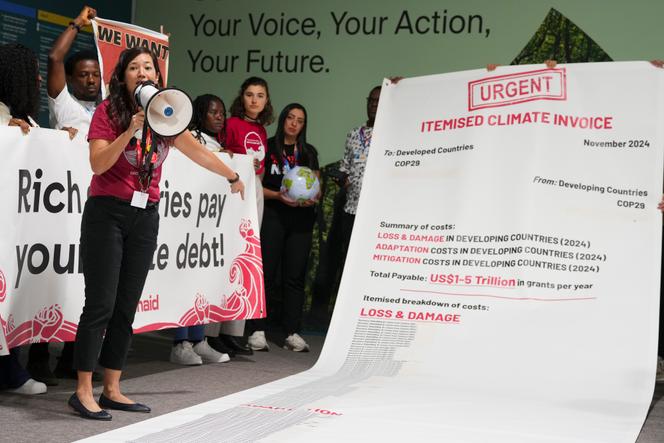

In Baku, countries are due to adopt a new global climate finance target. This is to replace the one set in 2009, which called for rich countries to mobilize $100 billion in annual aid to developing countries, a sum reached in 2022, two years late. Even when revised upwards, the future financial target will still fall far short of what is needed, which is now in the trillions of dollars, hence the idea of developing so-called innovative financing, which is feasible, scalable and equitable.

The working group's experts have first proposed a tax on international shipping, which they regard as the most mature proposal. This sector accounts for 3% of global greenhouse gas emissions. A tax of $150 to $300 per tonne of CO2 equivalent could raise up to $127 billion a year between 2027 and 2030, an envelope that would then shrink until 2050. The idea of such a levy is one of the options in the action plan to be presented by the International Maritime Organization in 2025 to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050.

Taxes could also be introduced in the aviation sector, responsible for 2% of global emissions. The experts have proposed taxing kerosene on commercial aircraft and private jets, which could generate, in the former case, 18 billion euros a year at 0.33 euros per liter. They have also suggested introducing a ticket levy for luxury classes (business, first) and for frequent flyers. A graduated tax, starting at $9 for the second flight of the year and rising to $177 for the 20th, would generate $121 billion a year.

You have 62.74% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.