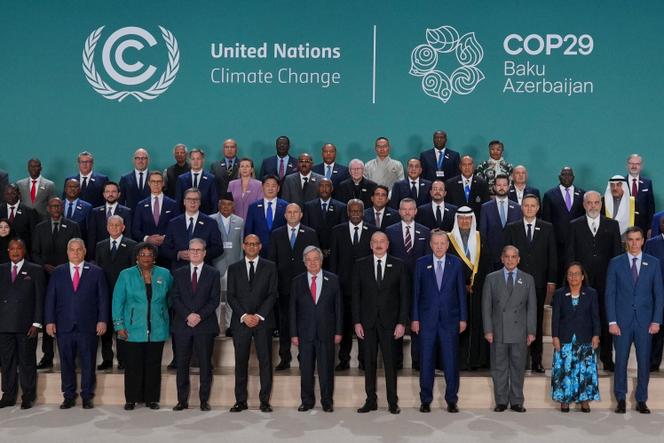

It was a stark tableau: testimonials about climate change's consequences delivered to chairs left empty by major nations' leaders. On Tuesday, November 12, the second day of the 29th Conference of the Parties on Climate Change (COP29) in Baku, Azerbaijan, nearly 80 world leaders took to the podium.

The United States, China, India, Canada, and Japan sent no representatives. The same was true for climate diplomacy heavyweights like France and Germany. These absences created space for some 30 African leaders, representatives from "small islands" and Central Asian countries – all struck by intensifying climate "hazards" and concerned about multilateralism's crisis amid wars in Ukraine, Gaza, Lebanon, Yemen... "As we look around the globe, we see funds flowing freely to wage war, but scrutinized when it's for climate adaptation," declared Mohamed Muizzu, president of the Maldives.

Everyone had carefully crafted their words to describe the avalanche of disasters. Emmerson Dambudzo Mnangagwa, president of Zimbabwe, spoke of the "devastating" drought that "has negatively impacted nearly every aspect of life" in the country. Philip Isdor Mpango, vice president of Tanzania, estimated that his country was losing "2% to 3% of its gross domestic product [GDP]" due to climate disruption. Tiemoko Meyliet Koné, vice president of Côte d'Ivoire, warned that "2 million" of his compatriots "could fall into extreme poverty." Sadyr Japarov, president of Kyrgyzstan, was moved by the melting of glaciers, while "the daily lives of many people living downstream depend on these ecosystems." Each came to show their goodwill, discussing national adaptation plans, and greener mobility policies.

But they all also went to Baku to question the developed countries. "We have to relocate our houses," Ahmed Abdullah Afif Didi, vice president of the Seychelles, said, asking where the country was supposed to get the money to pay for it. "There were many commitments at COP28, COP27, COP26... Let's do everything we can to turn our words into action."

Each time a representative of the Global South took to the floor, the crucial subject of COP29 emerged a little more: For the next 10 days, negotiators will be working hard to untangle the threads of the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG). The text is intended to replace the $100 billion target for aid from developed to developing countries, which was not reached until 2022, two years late – or $116 billion, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

You have 61.43% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.