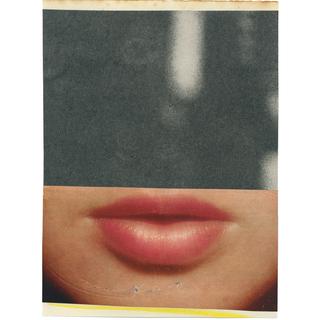

Cinema's devastating obsession with girls and young women

Long ReadEver since Stanley Kubrick's 'Lolita,' the persistent fantasy of the young girl being molded by her Pygmalion has served as a pretext for powerful directors to abuse young women.

On screen, they were beautiful and young and seemed happy, liberated and free-spirited. They were 13, 14, 15, 17 and 22, embodying youth, desire and independence. And today, some of them, now adults, have begun to tell the story of the trap they fell into. Flavie Flament, Vanessa Springora, Adèle Haenel, Charlotte Arnould, Judith Godrèche, and Isild Le Besco don't belong to the same worlds, they weren't the same age, and they didn't know or barely knew each other. But they have all begun sharing the same story: that of a lie and of a youth torn to shreds.

Each in her own way, these women have re-examined what happened to them. In her book Le Consentement (Consent, 2020), Springora describes the trap laid by the pedophile (in this instance, the writer Gabriel Matzneff), who turned his victim into an accomplice − "You loved me," he claimed. Journalist Hélène Devynck's Impunité ("Impunity," 2022), about the star news anchor Patrick Poivre d'Arvor, describes a system of which she herself was a victim, one that portrays young women as dolls and silences them. Godrèche, in her 2023 series Icon of French Cinema, looks back on her journey from child-object in the hands of filmmaker Benoît Jacquot to a woman assuming the storytelling reins.

They have all drawn attention to the tightknit nature of these "families" – film, media, and art – who rally around their great men. "It's not what we're forced to do that destroys us, but what we consent to that chips away at us; these tiny shames, of consenting daily to reinforce that which we condemn," writes Lola Lafon in Chavirer ("Capsizing," 2020), another story about a young girl who was abused.

The ingénue in search of freedom

Since the start of #MeToo in France, the story told by many of the women who have spoken out has followed the same narrative arc as those from novels of apprenticeships turned tragic: that of a woman, ranging in age from prepubescent girl to young adult, crossing paths with a much older man who, on the pretext of introducing her to a trade or profession, takes control of her against her will. This fantasy has played out throughout literature and cinema and has led to the caricature of the nubile girl in a velvet jacket, bangs falling over her eyes and a Sade novel tucked into her pocket. These girls have now become women and have decried this fantasy of possession: They didn't consent and were not given a choice.

This is what 41-year-old American actress and director Brit Marling, one of many actresses to accuse producer Harvey Weinstein of sexual assault, wrote in The Atlantic in 2017: "Part of what keeps you sitting in that chair in that room enduring harassment or abuse from a man in power is that, as a woman, you have rarely seen another end for yourself. In the novels you've read, in the films you've seen, in the stories you've been told since birth, the women so frequently meet disastrous ends." For the image of the young girl is a fundament of our culture, feeding our imaginations.

You have 88.7% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.