Perhaps the most striking feature of the annual session of the Chinese parliament, which opened on Monday, March 4, was the absence of the press conference that, for the past 30 years, every prime minister has held at the end of this essentially formal assembly. Xi Jinping, who has never deigned to answer journalists' questions since coming to power in 2012, probably didn't appreciate that in 2021, then premier Li Keqiang took advantage of the only opportunity he was given each year to speak to the press to point out that 600 million Chinese citizens were living on less than 1,000 yuan (around €120) a month. This assertion seriously undermined Xi's claim of success in the fight against poverty. With Li due to leave office in 2023, Xi took the opportunity to put an end to this ritual.

It would be wrong to see this decision as nothing more than a battle of egos. It goes hand in hand with another reform: Since 2020, the length of this parliamentary session has been reduced from around two weeks to just one.

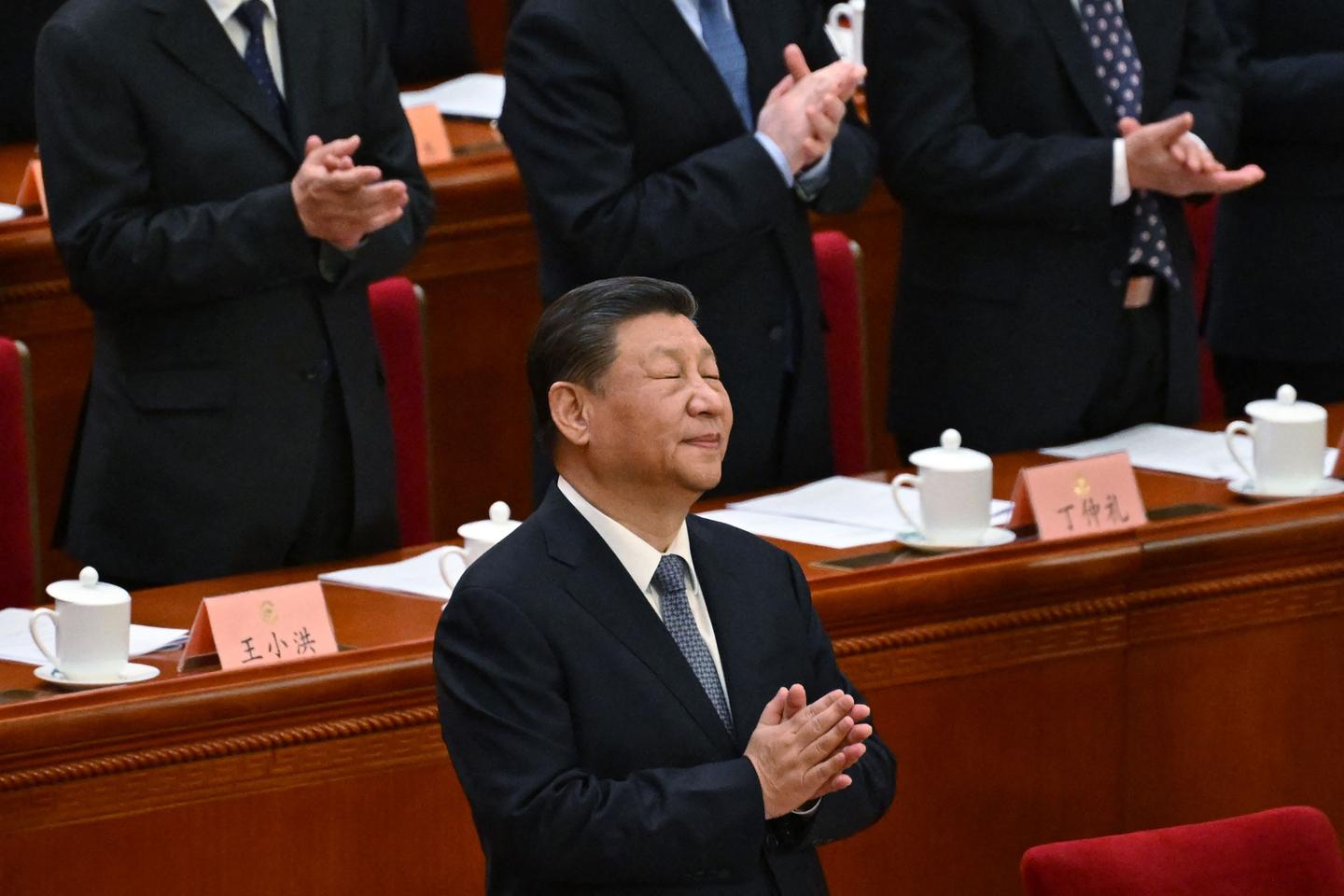

The meaning of these two changes is all too obvious. In Xi's China, the state is first and foremost at the service and command of the Communist Party. Xi likes to use his title of president of the Republic on the international stage, but in reality his two other functions – general secretary of the Communist Party and chairman of the Central Military Commission – are the most important in the exercise of power.

Disturbing return to origins

In the 2000s, Xi's predecessors had increased the prerogatives of the state to the detriment of the party. This was a way of proving to the rest of the world – and to the Chinese themselves – that the last page of Maoism had been turned. But Xi has always seen this separation of powers – however relative – as a threat. As a true Leninist, he is convinced of the primacy of the party over the country. It is the Communist Party's flag, not that of the People's Republic of China, that covers Mao Zedong's body in the mausoleum in Tiananmen Square.

This return to Xi's roots is worrying but not surprising. It is in line with the change in the Constitution which, since 2018, put an end to term limits, allowing Xi to stay in power as long as he likes, again breaking with the policy launched when Mao died in 1976.

Unsurprisingly, this primacy of ideology is accompanied by a strengthening of measures designed to protect "national security," which in practice gives the party more power to attack its supposed "enemies" at home and abroad. While China's leaders regularly claim, notably to the international business community, that they want to deepen the policy of reform and opening up to the world, the facts show the opposite. More than ever, Xi is driven by one motive: the interests of the Chinese Communist Party.

The main victims of this all-powerful party are the Chinese themselves. Not only because any semblance of civil society is nipped in the bud, but also because the primacy of ideology threatens to disrupt the smooth running of the economy. Will this hardening of attitudes last? For a long time, the country's prosperity in recent years made it acceptable. If prosperity were to falter over the long term, its justification in the eyes of the Chinese could also end up being blunted.