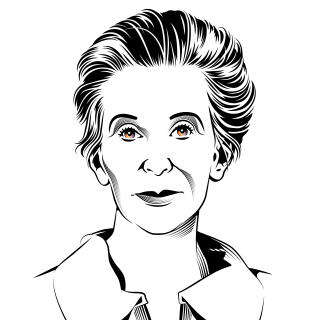

Catharine MacKinnon: 'Consent is the main legal and social excuse for doing nothing about sexual coercion'

InterviewIn French rape trials, the focus is more on the plaintiff's state of mind than on the accused's behavior, explains the American feminist legal scholar, who explains how she has affected the national debate by publishing 'Le Viol redéfini' ('Rape redefined')

A legal scholar and philosopher, born in 1946 in Minneapolis, Minnesota, Catharine MacKinnon is a major figure of "second-wave feminism" in the United States and worldwide. In the 1970s, she honed her philosophy through activism with the women's emancipation movement. As a student at Yale Law School in Connecticut, she defined the concept of sexual harassment in the workplace and, through her advocacy, helped to enshrine it in American law.

In the following decade, she tackled pornography as sexual discrimination, and in particular, with radical feminist activist Andrea Dworkin, drafted an ordinance regulating the filing of complaints by people directly or indirectly victimized by the pornographic industry. In 1990, she suggested a legal framework for prostitution, which came into force in Sweden in 1999, removing all penalties for sex workers, while criminalizing their exploiters – both "buyers" and "sellers" – in a model that inspires French law today. She also developed the concept of rape as an act of genocide and fought to incorporate it into international criminal law. She holds a chair at the University of Michigan Law School, has been a visiting professor at Harvard Law School in Massachusetts since 2009, and continues to work as a lawyer for victims of patriarchal domination.

You've worked mainly in American and international law for fifty years, so why publish a book on consent and the law in France today?

French law on rape already does not include nonconsent as an element in the Civil Code definition, although it comes up persistently in cases to contraindicate the explicit legal terms, especially contrainte [acts through which someone is forced to do something]. Now, public discussion in France, you may have heard, is considering adding consent more explicitly. Experience and analysis, with data on outcomes where it has long been used – principally the U.K. and its former colonies – shows that this would be a disastrous step backward. Instead, the opportunity is open for France, after revelations of #MeToo and recent brilliant books by French women, exposing sex imposed in contexts of inequality, to add explicit recognition of active exploitation of all inequalities, as admirably defined in other areas of French law, to the legal definitions of sexual violation in the Civil Code.

You are in contradiction with the law expert Catherine Le Magueresse, in particular, who argues in favor of introducing the notion of effective consent into French law...

You have 75% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.