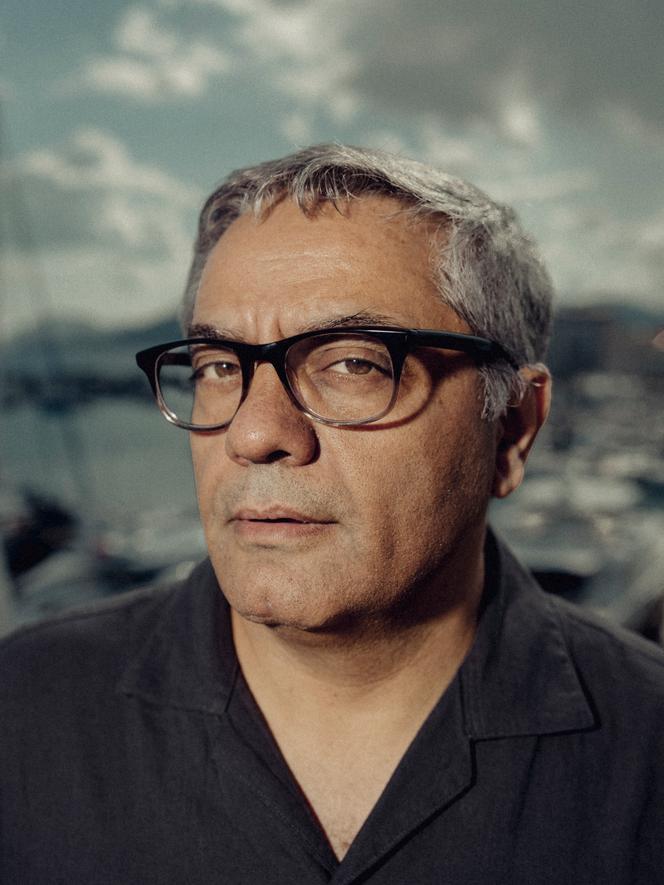

He has lost none of his energy. Built rough, with a dull complexion and graying hair, Mohammad Rasoulof came to our meeting place on Thursday, May 23, in the middle of the Palais des Festivals in Cannes, alone, anonymous, smiling beneath his drawn, intact features. "I didn't want to go back to prison," he summed up. "I have been before. I was in solitary confinement for 40 days in a room as big as this sofa. Then in cells not much bigger. No physical torture – they avoid it with people who have access to the media – but other things like not letting you go to the toilet for hours, which means you don't dare eat or drink... And then I've been in prisons where you're practically free to move around. I've seen some amazing things. Thieves who had had their fingers cut off because that's the penalty under Islamic law. They have a kind of little guillotine for that. Except that immediately afterwards they send the convicts to hospital to have them transplanted again. Because, while Islam says you have to cut them off, it doesn't say you can't glue them back on. They send them back to prison with their grafts. Some take, others don't. They're all there with their bandages..."

Rasoulof has just crossed Iran's borders on foot, through the mountains, to escape an eight-year prison sentence, including five years for "colluding against national security." You can't help but admire the resilience of the director, who loves nothing more than to unravel the ambivalence of his fellow human beings. On Friday, May 24, the Festival's clandestine exile is presenting The Seed of the Sacred Fig in competition. It is the story of a judge faced with the weight of his decisions at a time of popular revolt. The mullahs in Tehran have already banned the film.

As with his previous films, which pointed to social misery (Iron Island, presented at the Directors' Fortnight in 2005), repression, exile, corruption (Goodbye, 2011; Manuscripts Don't Burn, 2013; A Man of Integrity, 2017; all presented in the Un certain regard section), or the banality of evil (There Is No Evil, Golden Bear winner in Berlin in 2020), the director has this time again bypassed the bans. He did everything "to be able to work without anything getting out. We really took every precaution. Once it was in post-production, I had no worries. The film was no longer in Iran. It was being worked on abroad, but during the whole shoot, I was really worried."

When the disfavorable result of his appeal trial came out a month ago, he had a few hours to decide: exile or jail. Eventually, he threw away the electronic devices, the phones that could trace him, and left. It took him three weeks in hiding to reach his daughter, who is studying medicine in Germany, where he was granted political asylum. And although he no longer had a passport, Berlin and Paris agreed to allow him to attend the Cannes Film Festival. Of his journey, he said little more. "There are still a lot of people who are likely to need to leave Iran. In general, this kind of route is passed on in secret inside the prison. It's best not to talk about it outside..."

You have 57.12% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.