Did our extinct ancestors and cousins show compassion, helping others weakened by injury, illness or old age? Several cases have already been documented among Neanderthals but some anthropologists continued to wonder whether these examples related to circumstances where the attention paid to others was truly selfless, or whether it was motivated by a more selfish sense of reciprocity, in anticipation of possible hard times.

The Cova Negra cave, near Valencia in Spain, proposes an answer to these questions. It has been excavated since the 1930s, revealing bones attributed to Neanderthals who occupied it between 273,000 and 146,000 years ago. Looking back at faunal remains found on the site in 1989, Mercedes Conde-Valverde (University of Alcala, Madrid) and her colleagues discovered several human bones, including an immature temporal bone, dubbed CN-46700, attributed to a Neanderthal child who would have been just over 6 years old at the time of his death.

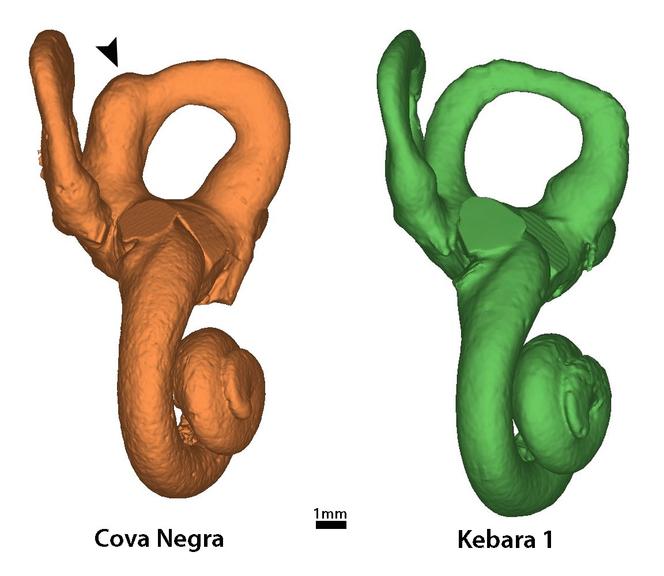

Tomographic imaging revealed the structure of the semicircular canals that make up the inner ear. One of these canals was abnormally shaped. This pathology was most likely associated with trisomy 21, according to the Spanish researchers who believe that the symptoms linked to this malformation would include, "at a minimum, severe hearing loss and markedly reduced sense of balance and equilibrium."

"Thus, the care necessary for their survival over a period of several years likely exceeded the capabilities of the mother and would have required the help of other members of the social group," they wrote in Science Advances on June 26. Until the 1930s, life expectancy for people with Down syndrome was just 9 years, they pointed out, and 12 in the 1940s, compared with over 60 years today in developed countries.

They added that "the case of the CN-46700 individual is particularly interesting because social care was destined to an immature individual who had no possibility to reciprocate the assistance received." In conclusion, they argued that "the presence of this complex social adaptation in both Neanderthals and our own species suggests a very ancient origin within the genus Homo."

This has been hailed by independent Australian anthropologist Lorna Tilley, who works on the "bioarchaeology of care": "I have no doubt about the provision of social care – and health-related care in particular – in this particular case and in Neanderthal society more generally, as there is plenty of compelling evidence for it."

You have 53.73% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.