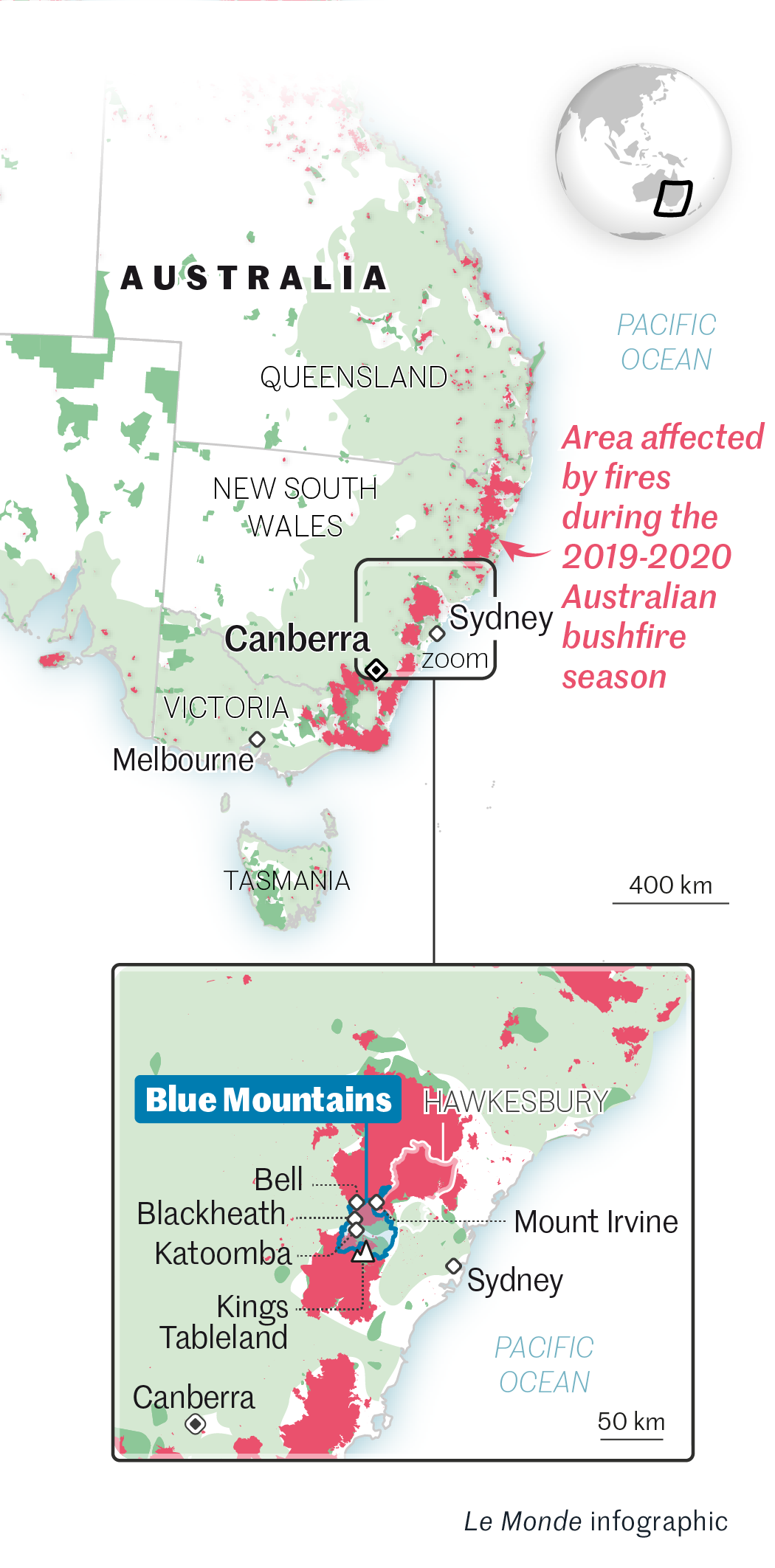

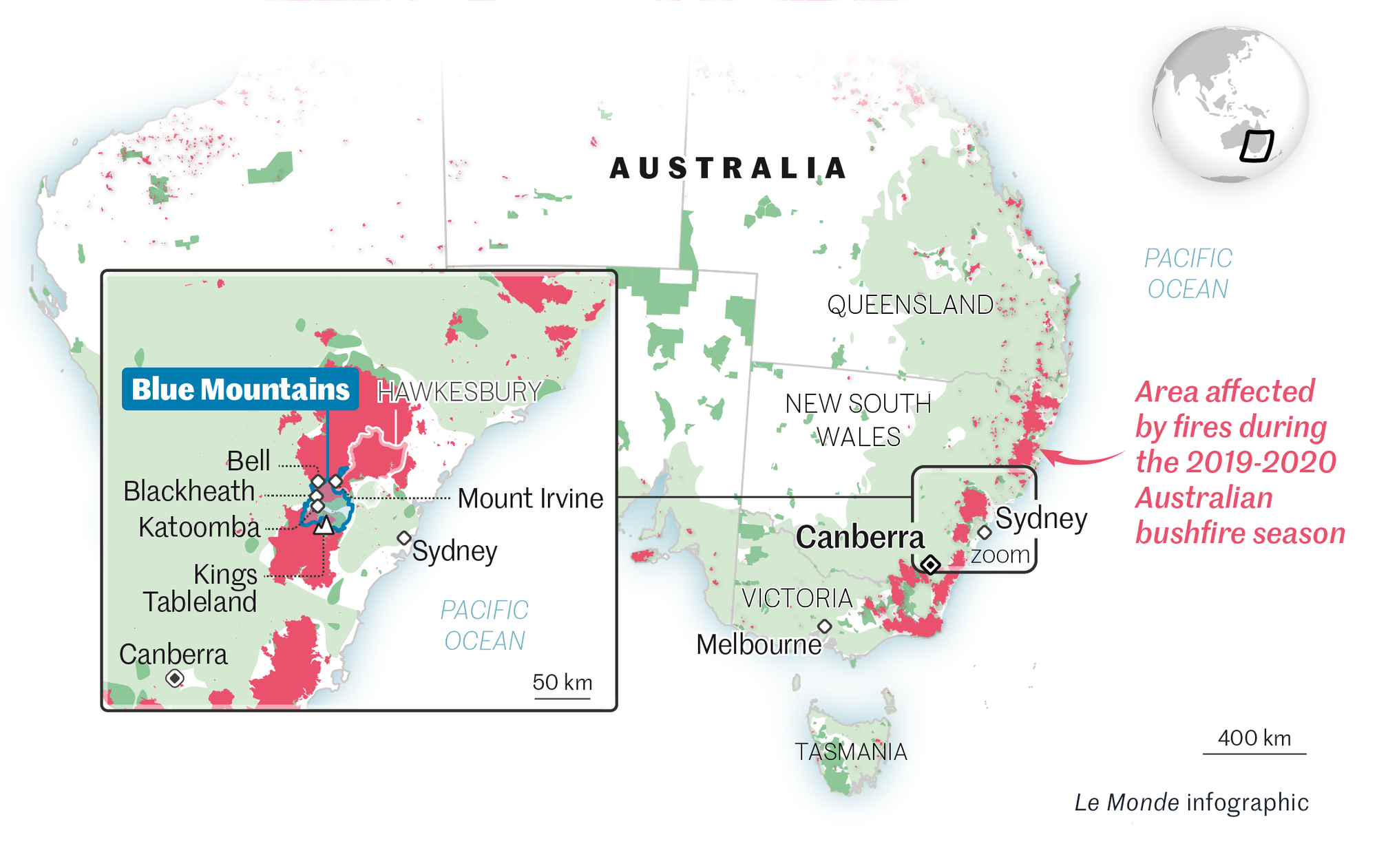

Australia after 'Black Summer': A slow recovery from the 2019-2020 megafires

Feature'Living after a disaster' (2/6). The Blue Mountains saw 80% of their forest cover destroyed during the 2019-2020 Australian bushfire season. Since then, nature has somewhat regenerated, but locals dread the aftermath. To better fight future blazes, they're turning to traditional Aboriginal techniques.

On one night in January 2020, darkness had engulfed the Blue Mountains, to Sydney's west, for several hours when volunteer firefighter Sarah Hyde awoke with a start. Through the window, she saw her brigade's red trucks. They were waiting for her, all sirens blaring. Immediately, she put on her uniform: heavy yellow jacket, pants and helmet, and rushed out into the street. "And then, nothing. There was nothing. No vehicle. No fire. I was alone: a madwoman, in the middle of the road," she recalled, three and a half years later, her eyes brimming with tears at the mere mention of this hallucination.

The megafires that ravaged the continent-sized island country between October 2019 and February 2020 have continued to haunt its inhabitants: Hyde, a speech therapist, is still struggling with post-traumatic stress disorder since December 15, 2019, when she found herself trapped by flames, one of which climbed up her back and set her long hair ablaze.

That summer, "Black Summer," as Australians have dubbed it – hundreds of fires swept across 24.3 million hectares of land – an area larger than Tunisia – claiming the lives of 33 people, destroying a fifth of the country's forests, killing several hundred million animals and endangering one-of-a-kind ecosystems. The Blue Mountains area, a 1 million-hectare forest area of exceptional biodiversity – which is listed as a Unesco World Heritage Site – was hit particularly hard: Eighty percent of its surface area was affected by fires. Since then, everyone has been slowly recovering and preparing for the future. According to the findings of the Royal Commission on National Natural Disaster Arrangements, published on October 28, 2020: "What was unprecedented is now our future."

"On the day of my accident, everything was just chaos. It felt like rivers of lava were flowing down from the treetops. Trunks were falling onto the roads. Embers the size of dinner plates swirled in the air. And there I was, in the middle of this inferno, in charge of the fire hose's supply system, pathetic, powerless," said Hyde, who threw herself to the ground to extinguish the flames on her and got up, unhurt but "wrecked."

She soon left the village founded by her great-grandfather – Mount Irvine, a hamlet of nine souls where life is punctuated by the songs of lyrebirds – and has since settled close to her workplace, to get away from those memories which the drive through the blackened eucalyptus forest brought back to her every day. But they have stayed deep inside her, like a pain she can't get rid of. This is what her father, Allen Hyde, realized one day in June, shocked to discover her still so wounded. The findings of a preliminary study published by the Australian National University in 2022, "shows that people affected by disasters are at increased risk of ongoing mental health challenges."

You have 83.5% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.