Calling an exhibition "Pop Forever" may seem excessive. Is pop, then, a timeless concept? Or, at the very least, does it have a long-lasting relevance? Beyond the unnuanced flashy title, should it take its place among the categories that art history and aesthetics have long reveled in, such as classical or baroque? To assess this, we need to start by defining pop art, its principles, its ends and its means.

This is no easy task since many of the characteristics of the various manifestations of pop art over the last 60 years or so have been apparent in so many different places. We'll define "pop art" as any artistic representation of contemporary life, revolutionized by countless scientific, technical and industrial advances, with digital technology being the most recent. In other words, pop art is the realism of the second half of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century.

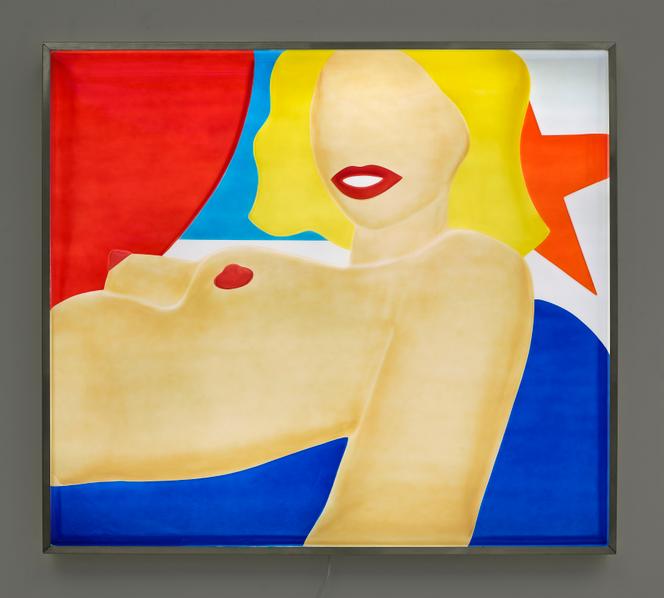

Just as there was a pictorial realism of everyday life in Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, Flanders and France in the 17th century (Caravaggio, Velazquez, Vermeer and the Le Nain brothers), and as there was a second one in the 19th throughout Europe (Courbet, Manet and Menzel), a new realism appeared and became widespread after the Second World War. This movement is the one that we've come to refer to as pop art. It was first used in the field of visual art before being taken up by the music industry, creating a great deal of confusion. "Pop Forever" at the Fondation Vuitton Foundation in Paris is not about the Rolling Stones or David Bowie, but about Andy Warhol and his contemporaries, with Tom Wesselmann (1931-2004) as the central figure.

There's an obvious difference between the three forms of realism mentioned above. The first two are essentially pictorial, while the third is not uniformly so and, more often, proceeds differently, through collage, assemblage and ready-made. It uses electricity and photographic reproduction processes. It includes the sound of the radio and the screen of the television.

The comparison between a still life in oil on canvas or wood by the Dutch artists Willem Kalf and Pieter Claesz, executed with a mastery of light passing through glass or gliding over earthenware, and a still life by Wesselmann – who explored this genre extensively – may seem surprising at first. However, both Kalf and Claesz used their compositions to bring together objects, shells and fruit that, in their time, symbolized luxury, exoticism and the circulation of goods. Similarly, Wesselmann brought together real or figurative objects such as bath towels, tin cans and transistors, which, in his time, signified comfort, consumption and the flow of news and advertising. Essentially, they both performed the same task: arranging on a flat surface or in bas-relief representative samples of the societies they inhabited, whether in Paris and Amsterdam for Kalf or in New York for Wesselmann three centuries later.

You have 61.41% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.