Anne Krueger: 'Inflation in the US may have peaked, but interventions still have plenty of momentum'

It is said that if you put a frog in boiling water, it immediately jumps out; but if you put it in cold water and gradually turn up the heat, it does not react – and is eventually boiled to death. Something similar can happen to economies.

Both inflation and the ad hoc interventions – sometimes referred to as industrial policy – distort the economy and result in lower economic growth. But inflation triggers a quick response. An economy-wide phenomenon, it gains momentum as one group after another seeks to restore or increase its real returns.

At a certain point, people begin to object. From then on, as the rate of inflation rises, pressure on policymakers to reduce it intensifies. Once inflation is subdued, growth can resume.

By contrast, the impact of targeted tariffs and industry-specific measures at any point in time, or in any one sector of the economy, is usually relatively small. Though they contribute inflationary pressure, reduce the economy’s flexibility, and weaken growth, they tend to be less noticed than a surge in inflation, so the public is unlikely to reject them.

Moreover, the prospect of lowering a tariff or removing a subsidy is typically met with strong resistance by the affected industry. So, whereas curbing inflation is a political imperative, reversing distortionary ad hoc measures is politically difficult.

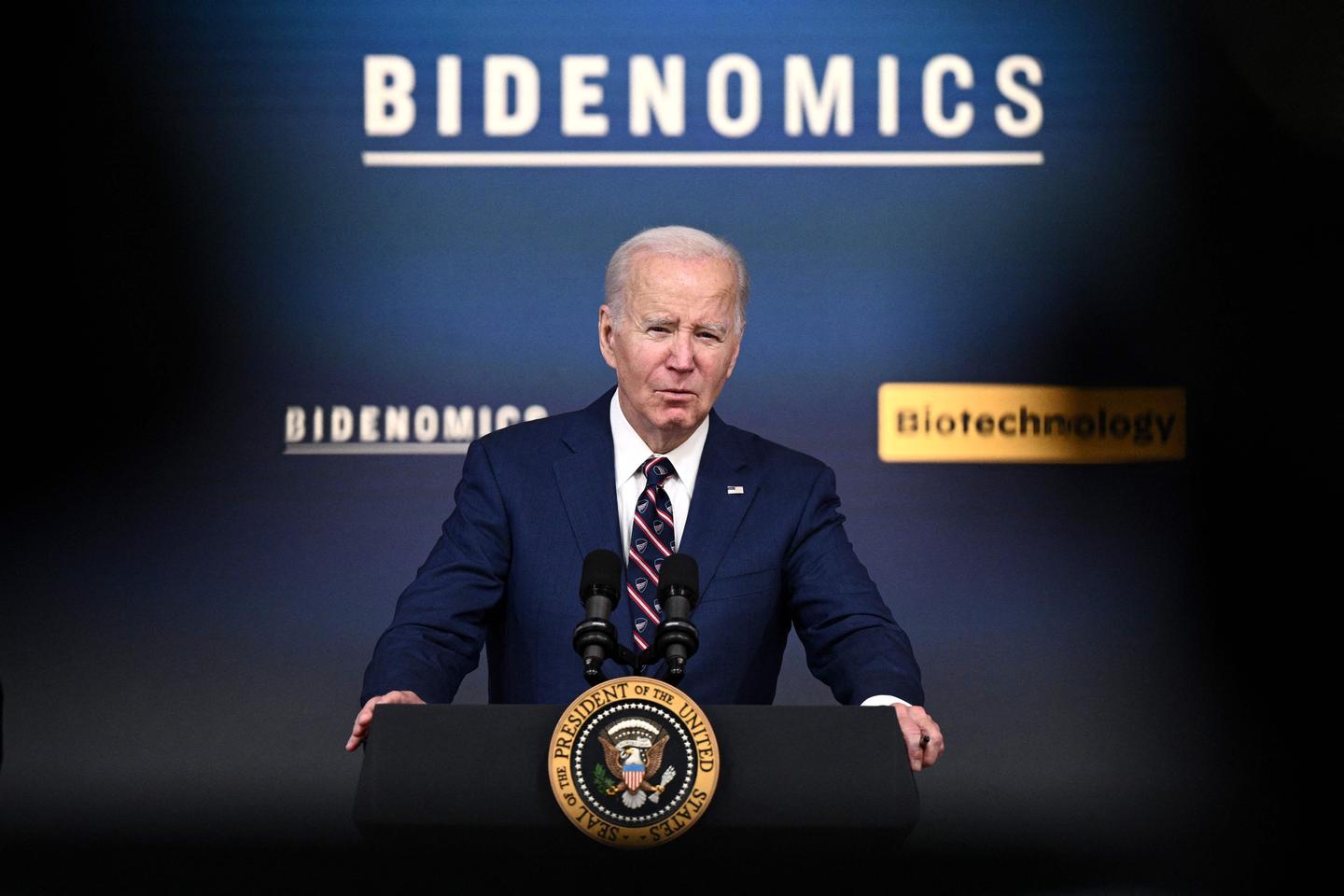

The United States today illustrates this dynamic. US President Joe Biden’s administration has bemoaned inflationary pressures and supported the US Federal Reserve in its efforts to rein in price increases. But it has also sharply increased government expenditure through the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), and introduced or upheld widespread industry-specific regulations, most of which are inflationary.

Risk of reprisals

Inflation may have peaked in the US, but ad hoc interventions still have plenty of momentum. Donald Trump’s tariffs on steel and aluminum imports – which Biden did not remove – have resulted in the world’s highest steel costs. This means that production costs are rising in any industry that relies on large amounts of steel – say, automobile manufacturers. Meanwhile, American producers of electric vehicles are receiving subsidies and tax breaks. Some interventions, such as subsidies, can be dangerous, not least because they can suggest favoritism and even outright corruption.

The Biden administration is also imposing tariffs on solar-panel imports, despite its concern for the environment. It has created large subsidies and other incentives for investment in semiconductors and batteries. It has capped the price of some prescription drugs, such as insulin, for elderly Medicare patients, with price ceilings set to be imposed on additional drugs each year, and has introduced a requirement for the government to negotiate prices of some drugs – measures that could lead to shortages and impede the development of cheaper generic drugs.

You have 40% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.