Imagine the poet Petrarch (1304-1374) trekking hundreds of kilometers through the medieval night from one monastery to another. The year was 1333. After studying in Carpentras (southeastern France), Montpellier and then Bologna (Italy), this son of an Italian pontifical notary, who had taken refuge at the court of Avignon, had already fallen in love with Laure, whose love he would sing all his life. He read Cicero and Virgil and collected the scattered fragments of Titus Livius' Roman History. It was then that he left Avignon, "the hell of the living, the cesspit of the earth, the most stinking of cities," for Paris, then Liège (Belgium), and eventually as far as Aix-la-Chapelle (Germany), via the Ardennes.

There, in the secrecy of monastic libraries, he discovered the manuscripts of forgotten Latin authors such as Propertius and Quintilian. He recopied them, exegeting them. While surveying ancient letters, he built the first of the humanist libraries. In his house at Arqua, near Padua (Italy), he shaped what Cicero called the "culture of the soul" and paved the way for other manuscript hunters, such as Poggio Bracciolini, who rediscovered texts by Tacitus and Vitruvius. As such, he became one of the founding heroes of a new cultural era: the Renaissance.

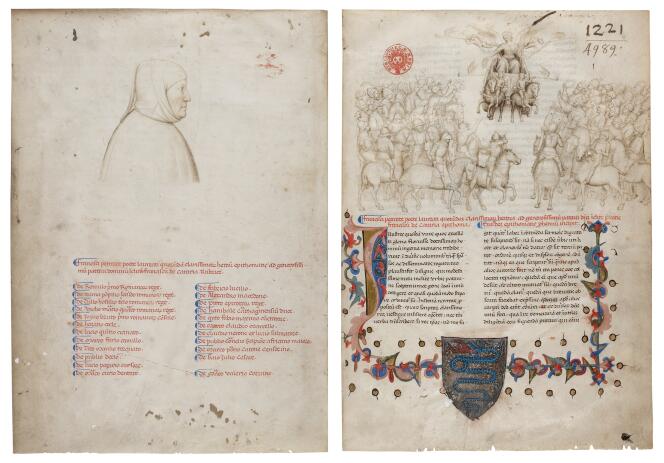

On its Richelieu site in Paris, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BNF) retraces his saga, and that of some of his peers, in a marvelous exhibition: "L’Invention de la Renaissance" ("The Invention of the Renaissance").

It's hard to tell the story of a turning point in history, to evoke the birth of a thought through images. The BNF takes up the challenge with pedagogy and poetry, punctuating the display with a few paintings, such as Perugino's Apollo and Daphnis, and above all with some of the most precious manuscripts, such as the Grand Ptolémée d'Henri II. From illuminations to writings, they tell the story of how this ideal, international community of scholars came together in the "Republic of Letters" over the years.

Long before the invention of the printing press, their members were free from any academic or ecclesiastical tutelage, enabling them to disseminate the ancient knowledge that would form the basis of the Renaissance. They hand-copied the treasures they unearthed and translated the original Greek or Latin into what were then known as "vulgar" languages. The production of luxury copies, fabulously illuminated, soon brought this knowledge into princely libraries.

The studiolo was born: There wasn't a prince in his palazzo in Mantua, Ferrara or Urbino who didn't have his own study devoted to reading and learning. The Montefeltros, the Sforzas, the D'Este – all literate princes surrounded themselves with books, globes, scientific tools and rare or precious objects. From wood marquetry to portraits of illustrious men, the BNF traces the evolution of this private room, the ancestor of the cabinet of curiosities. A monastic legacy from the Middle Ages, the term first appeared in the 14th century at the court of Avignon, in the Latin form of studium.

You have 45.7% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.