It was an extraordinary time. More than 300 million years ago, dragonflies were the size of our eagles, and scorpions the size of our dogs. Paleontologists called this phenomenon "Paleozoic gigantism" and debated its causes. Some attributed it to an excess of oxygen in the atmosphere during the Carboniferous period (between 358 and 298 million years ago). Others noted that arthropods, the first animals to emerge from the waters, had little competition for plant resources. Alone at the "bar," they probably took full advantage of it.

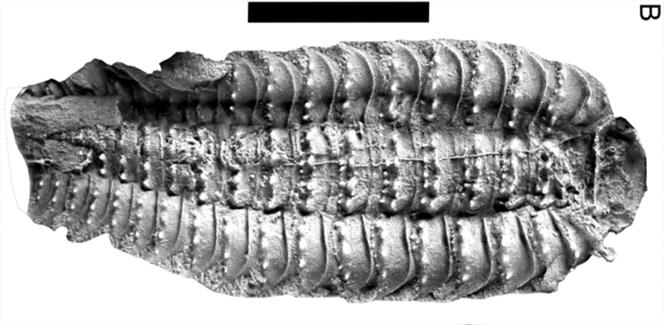

Arthropleura is an iconic example. Since 1854, when the first fossilized segments of the creature were discovered in Great Britain, this giant millipede has fascinated scientists. How did it live? What did it eat? And above all, what is this segmented creature, nearly 3 meters long? The term "millipede" itself is not scientific.

Myriapods – as they're aptly named – have sub-branches that comprise over 5,000 species divided into four classes. For the two main groups, English speakers have adopted centipedes and millipedes – simple and clear, even if the latter doesn't necessarily have 10 times as many segments as the former.

As is often the case, in the absence of a common name, the French language relies on scientific terms: Chilopoda and Diplopoda. The difference between the two? At the body level, the essential distinction is that the latter have two pairs of legs per segment, whereas the former have only one. This is why, based on the fossils unearthed, Arthropleura was clearly classified as a diplopod.

An article published on Wednesday, October 9, in the journal Science Advances by an international team coordinated by the Laboratoire de Géologie de Lyon has changed all that. Not only is the giant caterpillar not a simple diplopod, but the entire millipede phylogenetic tree will have to be revised.

In the early 1980s, French paleontologists have successfully analyzed two nodules discovered in coal mines in Montceau-les-Mines (Saône-et-Loire). At the time, the amateur paleontologists, supported by academics, understood that the four-centimeter-long fossils they had split in two contained a juvenile Arthropleura. However, they couldn't risk splitting any further, as this would probably have destroyed the specimen. Nor could they penetrate the rock to examine its interior – there was no technology to do so at the time. The stones therefore remained in the reserves of the Muséum d'Autun (Saône-et-Loire).

Mickaël Lhéritier, a PhD student in paleontology at the Université de Lyon, retrieved these fossils and subjected them to a technique now widely used in the study of ancient materials: X-ray tomography. As in a scanner, the sample undergoes successive cuts, but it also rotates. The result is a complete 3D image of the nodule's interior. "We saw a complete skeleton, with all 24 segments, right down to the head," said the young student. "Until now, we had never found more than 10 segments. And the head had remained a complete mystery."

You have 29.36% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.