10 years after 'Charlie Hebdo' attack, intellectual rifts have grown

InvestigationDebates in France on Islam, immigration, the Republic, secularism, anti-Semitism and freedom of expression have become more tense and divisive.

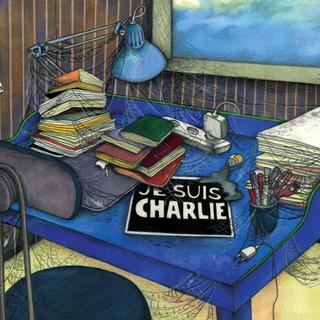

It was a human tide, like a republican communion. It was 2015, and yet it feels like an eternity ago. On January 11 of that year, the largest French demonstration since the post-WWII liberation took off across the country. Four days after the deadly January 7 Islamist attack, which decimated part of the editorial staff of the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, followed by the murder of a policewoman in the Paris suburb of Montrouge the next day and the anti-Semitic attack on the Hyper Cacher supermarket in Paris the day after that, over 4 million people marched behind banners that read "Je suis Charlie" – "I am Charlie."

Like an animated Eugène Delacroix painting, the people seemed to converge toward symbols of their freedom. Freedom of expression, represented by images of pencils. Freedom to believe or not to believe, under the defense of laïcité, or secularism. "It was as if citizens from all walks of life instinctively knew what brought them together," said sociologist Dominique Schnapper. Old anarchists, astonished, found themselves, just like in the singer Renaud's lyrics, stunned to have "kissed a cop" amid the Paris demonstration. The bells of Notre-Dame rang out for the Voltairean free spirits of Charlie Hebdo, while the Republic paid tribute to people who regularly railed against priests, imams and cops.

The impression of unanimity was, perhaps, misleading. Observers of democracy, such as historian Pierre Rosanvallon, were quick to point out that only "involved France" had mobilized for the demonstrations, while "marginalized France" – notably people from impoverished neighborhoods – had more often remained in the background. Some intellectuals, like Rony Brauman, had mixed feelings about demonstrating: "I had no disapproval of the demonstration, but I couldn't march next to Sergei Lavrov and Benjamin Netanyahu," recalled the former president of Doctors Without Borders. Others did not feel they were "Charlie": Undoubtedly, demographer Emmanuel Todd summed up the dispute in the most scathing way, writing, in Qui est Charlie? Sociologie d'une crise religieuse ("Who is Charlie? Sociology of a Religious Crisis"), that "millions of French people rushed into the streets to define the right to spit on the religion of the weak as a priority need of their society."

You have 89.34% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.