“If something cannot go on forever, it will stop” - Charles P Kindleberger, “Manias, Panics, and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises”, 1978

Every six months it happens like clockwork.

The first time the AI sector was rocked over fears of low/zero ROI, and gargantuan cash burn with nothing to show for it, was June 2024, when Goldman asked point blank if Gen AI was nothing more than "too much spend, too little benefit." i.e., a giant capital drain that will never lead to positive long-term returns for investors.

As Goldman's concern gained prominence, the tech/AI/ hyperscaler, etc sector saw its first major selloff in years, but since the market was already so flooded with liquidity, dip buyers quickly emerged and the brief tremor was quickly forgotten even as Goldman's question was never answered; instead it was assumed that sophisticated, super smart corporate CFOs could not possibly be so dumb as to allocate trillions in capex for what is ultimately a $20/month chatbot used primarily by college-age kids to cheat on their essay writing skills. Fear not, they said, a huge and much more expensive use case will eventually emerge, they said.

Unfortunately, 6 months later - when another $100 billion in capex had already been burned "perfecting" the world's most expensive chatbots/essay cheating platforms, no such use case had emerged. What did emerge however, was a major scare out of China which developed its notorious DeepSeek LLM, which was not only opensourced and massively cheaper than similar US offerings, but required far cheaper equipment than the latest NVDA superdupercard to run efficiently. Around this time we also got a handful of reports that companies like MSFT, GOOGL and META were quietly pulling back on their Capex spending (they were), and it all combined to result in the next big AI selloff, one which started in late January and continued until April, when everything collapse on Trump's Liberation Day meltdown... and which also promptly sparked the biggest rally in stock market history after Trump realized he likes his stocks higher than his tariff revenues. Nonetheless, it was the first time we reminded readers that what is happening in the sector AI is not that different at all from what we saw during the build out phase of the first dot com bubble, when companies like Global Crossing were all the rage for 15 minutes... and then they went bankrupt.

Which brought us to September when, with the AI bubble was now fully raging and singlehandedly pushing stocks to their highest valuation since the dot com bubble...

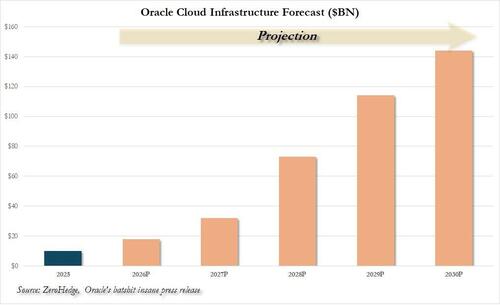

... Oracle crashed the AI bubble party on Sept 10 with all the grace of a bull in a China shop, when it unveiled one of the biggest circle jerk vendor financing deals of all time (more below), announcing a massive $300 billion, five-year cloud computing deal with OpenAI.

In retrospect, Oracle - which has since erased all of its gains from its deal announcement and almost all gains from its "batshit insane" hockeystick revenue projections which revealed the company added a mindblowing $317 billion in future contract revenue with just three different customers...

... could have been less painful had Oracle also not reminded everyone that it, drumroll, doesn't actually have the money to pay for this spending orgy which is now projected to last well into the 2030s (without any recession on the horizon, of course, because nobody ever forecasts a recession).

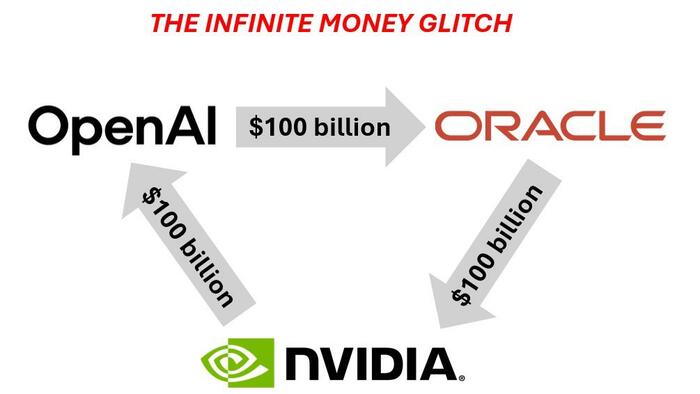

Ah yes: vendor financing with cash from operations is one thing. Vendor financing with cash from debt is something totally different, and as luck would have it, one of the most erudite voices on Wall Street, JPMorgan's Michael Cembalest did a very fine job of describing in simple terms what many of his peers have come to call the infinite money glitch "circular economy" of AI, and which looks something like this.

This is what Cembalest said in his latest Eye on the Market note (available here):

The Blob: the AI and data center takeover

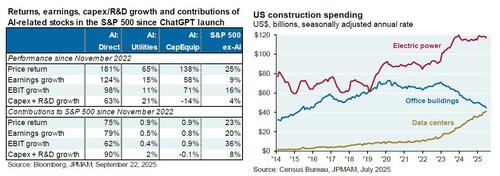

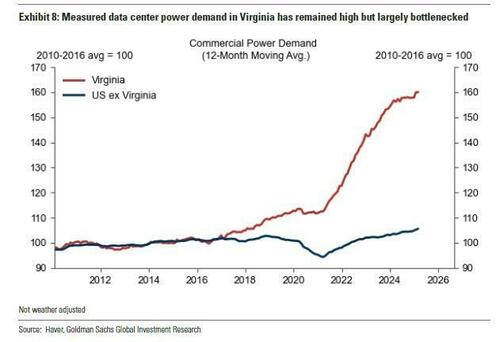

I think this is well understood, but just to reinforce the point: AI related stocks (1) have accounted for 75% of S&P 500 returns, 80% of earnings growth and 90% of capital spending growth since ChatGPT launched in November 2022. AI is showing up other places as well. Data centers are eclipsing office construction spending and are coming under increased scrutiny for their impact on power grids and rising electricity prices.

Specialized power rates for most data centers aren’t enough to cover costs of a new natural gas plant (leaving other customers to foot part of the bill), and in the PJM region, 70% of last year’s increased electricity cost was the result of data center demand. The biggest medium-term risk I can think of for top-heavy US equity markets: China’s Huawei and SMIC pierce the $6.3 trillion NVIDIA-TSMC-ASML moat by creating their own supernode computing clusters and deep-ultraviolet lithography machines of comparable quality.

Which brings us to the stunning punchline:

Other recent AI news: Oracle’s stock jumped by 25% after being promised $60 billion a year from OpenAI, an amount of money OpenAI doesn’t earn yet, to provide cloud computing facilities that Oracle hasn’t built yet, and which will require 4.5 GW of power (the equivalent of 2.25 Hoover Dams or four nuclear plants), as well as increased borrowing by Oracle whose debt to equity ratio is already 500% compared to 50% for Amazon, 30% for Microsoft and even less at Meta and Google.

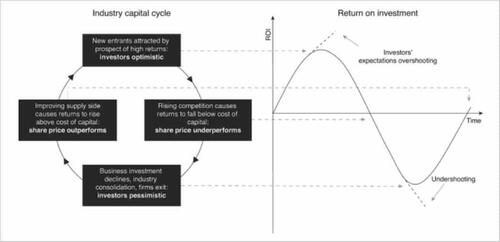

In other words, the tech capital cycle may be about to change.

Cembalest closes with the following quote from Doug O’Laughlin's Fabricated Knowledge substack:

Capital Cycles and Debt: There is no way for Oracle to pay for this with cash flow. They must raise equity or debt to fund their ambitions. Until now, the AI infrastructure boom has been almost entirely self-funded by the cash flows of a select few hyperscalers. Oracle has broken the pattern. It is willing to leverage up to hundreds of billions to seize a share. The stable oligopoly is cracking…The implications are profound. Amazon, Microsoft and Google can no longer treat AI infrastructure as a discretionary investment. They must defend their turf. What had been a disciplined, cash-flow-funded race may now turn into a debt-fueled arms race.

Others, such as Goldman's head of Delta One trading Rich Privorotsky, have been less polite when he describing what is essentially the same circular scheme:

As to the question where the funding for this AI revenue circle jerk will come from, regular ZH readers are aware that there is no such thing as a free lunch, and certainly no free data center. To be sure, there was a time when the growth in CapEx could be funded from Free Cash Flow, but now that CapEx has to grow at an ever exponential-er pace just to impress markets, the wheels are starting to fall off the bus.

Enter private credit.

While much of Wall Street is only now doing the analysis of comparing future free cash flow with projected capex, it was back in July that we wrote "The Shocking Math: Paying For AI Capex Will Require Over $1 Trillion In New Debt By 2028" (note available to pro subs) in which we quoted some stunning numbers from Morgan Stanley:

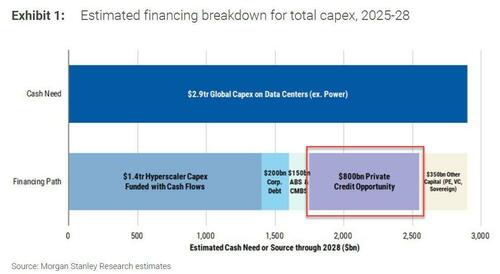

We forecast roughly $2.9 trillion of global data center spend through 2028, comprising $1.6 trillion on hardware (chips/servers) and $1.3 trillion on building data center infrastructure, including real estate, build costs, and maintenance.

This translates into investment needs of over $900 billion in 2028. For context, the total capex spending by all companies in the S&P 500 index combined was about $950 billion in 2024.

Such large potential spending has significant macro consequences as well. Our economists expect that investment spending related to data center construction and power generation will add up to 40bp to US real GDP growth between 2025-26.

That's the good news... which many will say is already largely priced in. The bad news, again, is who pays for all of this. And Morgan Stanley admitted as much:

By any measure, the capital requirements to support this level of investment are staggering, and mobilizing efficient and scalable capital becomes increasingly critical. We did a deep dive into this topic, exploring alternative avenues of capital to finance this expenditure, in a collaborative report published a few days ago. The key takeaway from the report is that credit markets – secured, unsecured, and securitized in both public and private markets – will play a growing role in financing data centers.

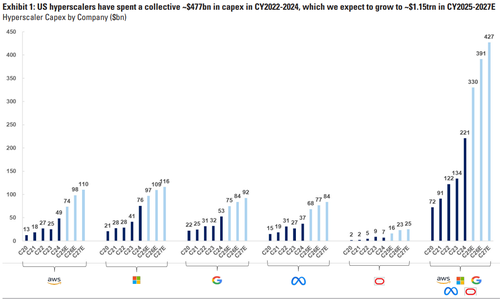

To be clear, capex related to AI and data centers has been in motion for the last few years. Spending from the hyperscalers alone has gone from ~$125 billion two years ago to ~$200 billion in 2024 and the consensus expectation is that it exceeds $300 billion in 2025.

Internal operating cash flows from the hyperscalers have been the source of this spending. However, our equity analysts expect the investment needs for data centers to rise sharply over the next few years. While cash flows from hyperscalers will remain a key source of capital to finance data center-related spending, these alone will no longer be adequate, after accounting for cash build and shareholder capital returns. Leveraging our equity analysts’ projections, we estimate that $1.4 trillion of hyperscaler capex may be self-funded with cash flows, leaving a sizable $1.5 trillion financing gap.

We think that credit markets, broadly defined to encompass both public and private markets of different flavors, will gain traction as more efficient providers of capital to bridge this gap. There is a favorable alignment of significant and growing dry powder across credit markets with attractive real yields on offer with appeal to a sticky end-investor base (e.g., insurance, sovereign wealth funds, pension funds, endowments and high net worth retail) looking for scalable, high-quality asset exposures that can provide diversification benefits. We think that this alignment of needs of capital and investment will pave the way for bridging the $1.5 trillion financing gap.

We size the different financing channels as follows: unsecured corporate debt issuance from issuers in the technology sector (~$200 billion); securitized markets in the form of data center ABS and CMBS (~$150 billion), private credit markets in the form of asset-based financing (~$800 billion), and other capital sources across sovereign, private equity, venture capital, and bank lending (~$350 billion). Of these, we think that private capital – in particular credit – will play a key role in meeting a majority of the remaining financing gap as it sits optimally at the intersection of significant expansion in AUM in a higher rate environment and the complex, global, and customized financing needs that are associated with AI build-out.

As MS concludes, "the point we want to drive home is that credit markets will play a major role in enabling AI-driven technology diffusion" and of all the available sources of credit, the chart below shows just how big the debt hole is that private credit will have to plug.

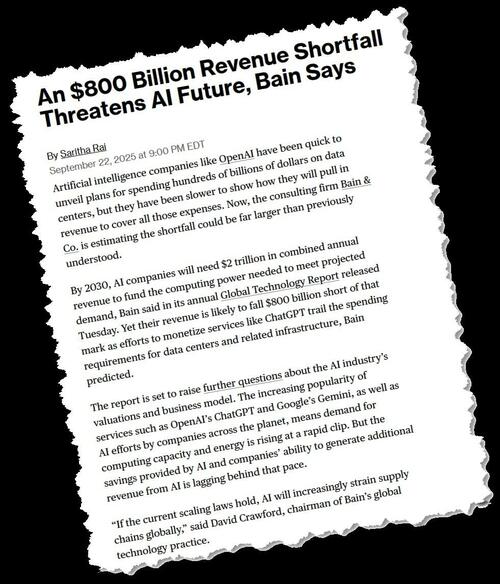

Incidentally it was about two months after we first highlighted the staggering $800 billion funding gap (which private credit will need to fill) when consulting giant Bain reached the same conclusion.

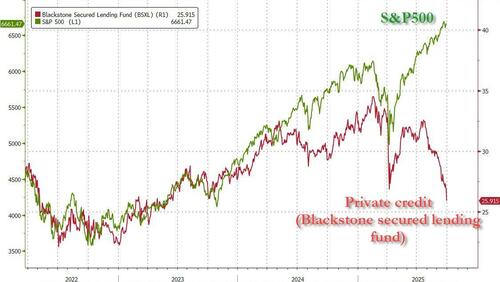

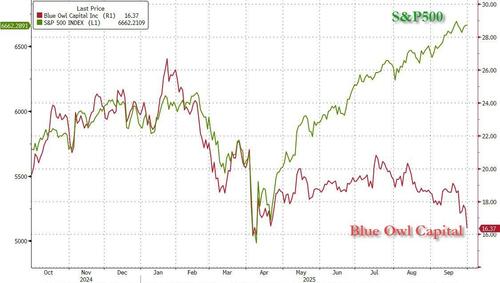

It is here that we encounter the first not so small problem: while one can pretend that equity growth is infinite, at least for the AI equity universe which as Cembalest above noted has contributed 75% of all S&P500 market cap gains since Nov 2022, when it comes to the fundamental analysis that at least some have done on the private credit backing these castles in the sky, things are turning very, very ugly: presenting exhibit A: the stock price of Blackstone's Private Credit BDC, i.e. the Blackstone Secured Lending Fund: today, BXSL just hit a 2025 low taking out the April Liberation Day bottom and is at the lowest level in over two years, having massively diverged with the S&P.

It's not just Blackstone: the big kahoona of private credit, Blue Owl, looks like it is about to fall off a cliff, having just traded at 2025 lows as well!

Blue Owl... Blue Owl...why does that name sound familiar? Oh that's right: the AI circle jerk is already aggressively using it to fund its multiple exploits:

The problem for Blue Owl, Blackstone and all the other key players that will soon be expected to provide no less than $800 billion to keep the AI circle jerk alive, is that - as their stock prices makes clear - they have much bigger problems than just funding some data centers. Perhaps the biggest problem, as we noted last week, is that these private credit giants are already massively exposed to the weakest link in the US economy, the US consumer, and especially the low-income US consumer, that BNPL expert whose NPLs (ironic that you can't spell BNPL without NPL) are about to skyrocket (especially now that student loans have to be repaid). No wonder why the Financial Review recently wrote that "Private equity is sitting on $5 trillion of existential dread" adding that "a staggering 18,000 private capital funds are trying to raise trillions of dollars. Something’s got to give, according to the industry’s biggest players."

Judging by the accelerating plunge in the stock prices across private credit lenders, we won't have long to wait. However, it begs the question: what happens to all the massive projected debt that private credit is supposed to provide if and when the entire industry is forced to shut down.

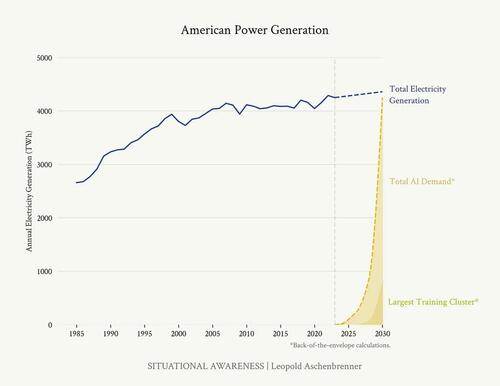

Keep in mind nowhere in the above analysis did we touch on the absolutely staggering funding needs to reboot America's ancient power grid which is woefully insufficient and inadequate to fire up the dozens of data centers which will be needed across the country in as little as 3-4 years if any of the stratospheric AI revenue projections are to come true...

... and if the rest of the US has any hope of catching up to the state better known as "data center alley."

But don't worry, we will cover all of this in a subsequent post and make it clear how absent trillions in government spending starting yesterday, there is zero chance of any of these pie in the sky forecasts ever coming true.

One thing we did want to cover in this post before we go, is whether we are living in a bubble (arguably the biggest bubble in history) and whether the AI bubble will burst any time soon. The honest answer: we don't know - with Nvidia stock just hitting a new record high, and its market cap rising to a staggering $4.5 trillion, clearly the AI thesis is still being bought.

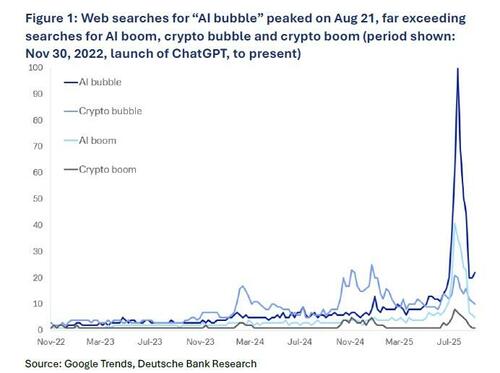

Yet one bubble that has certainly burst is the the bubble in saying there’s a bubble.

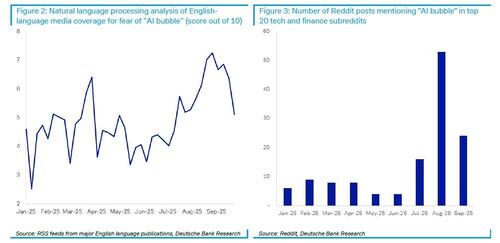

As DB's Adrian Cox writes today, the number of web searches for “AI bubble” has plummeted in the past month according to Google Trends.

Peak “AI bubble” was on Aug 21, shortly after a little-understood report from MIT appeared to suggest that hardly any organizations were getting a return from their investment in AI, and OpenAI CEO Sam Altman said investors might be getting “over excited”, prompting a 3.8% pullback in the Magnificent Seven tech stocks over five days (of course, that pullback is now long forgotten).

Since then, the number of web searches worldwide for “AI bubble” has fallen to 15% of that level. “AI boom” reached its own high a week earlier, at 40% of the “AI bubble” peak. Meanwhile, the bubble in “crypto bubble” references topped out in late January at a mere quarter of the AI version.

For some perspective, DB examined how the bursting of the “AI bubble” bubble reflects the pattern of past bubbles, why it might be happening now, how hard it is to time the market, what might be a better alternative, and how long this bubble may last unless, of course, “this time it’s different”.

The AI boom will stop but it may not pop. And while there may be a bubble, the moment everyone spots it may be the moment it is least likely to burst.

The internet is awash with reports and articles from experts, media organizations and – even – sell-side research houses offering variations on the theme “Is AI a bubble?”. For a sharp analysis, take a look at DB's interview with leading AI expert Azeem Azhar at our recent technology conference – AI is not a bubble (yet) amid surging demand – and his original report here. The bank also wrote recently in “The Summer AI Turned Ugly: Part 2” about whether valuations were excessive by various metrics.

However, web search data seems to indicate that the broader public has already moved on.

DB confirmed this with an AI-assisted natural language analysis of English language publications since the start of the year. AI-related investment concerns in technology articles reached a high point of 7.3 on a 10-point scale in the last week of August and have since subsided to 5.1. (The previous high of 6.4 was around the US Liberation Day tariffs in March.) DB's analysis of technology and finance Reddit posts mentioning an “AI bubble” showed the same trend.

Here, an old cliche: "identifying a bubble is almost impossible", not least because no one agrees exactly what it is – typically it’s something like “when asset prices rise significantly above intrinsic values” – nor what the correct intrinsic values are, even after it bursts. Concern may act as a pressure valve, lowering valuations and encouraging a whole new round of bargain hunting.

It’s a twist on the Hawthorne effect, where workers in an Illinois factory almost exactly 100 years ago appeared to be more productive under different lighting but turned out to be instead picking up the pace when they were aware they were being observed.

“This is a serious bubble. It makes biotech in 1991 look like a picnic”: Michael Murphy, Murphy Investment Management, Nov 19, 1998

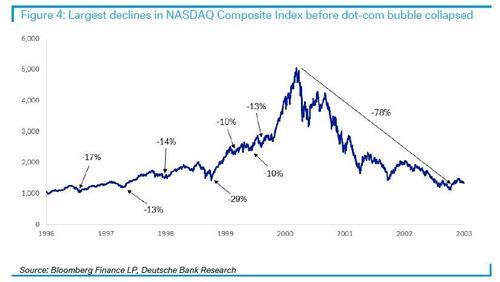

Bubbles are not neat linear processes. They typically inflate in several waves interspersed by dramatic falls. Looking at the dot-com bubble, the Nasdaq technology index surged and fell back by 10% or more seven times in the five years before it peaked on March 10, 2000. It also carried on shooting into the stratosphere well after talk of a bubble became

commonplace, doubling in the year to October 1999, then almost doubling again over the following five months until it turned.

Indeed, Bloomberg published a story on Amazon and Yahoo’s holiday earnings on Nov 19, 1998, quoting Michael Murphy, chief investment officer at Murphy Investment Management: “This is a serious bubble. It makes biotech in 1991 look like a picnic.”

That was when the Nasdaq was at less than 2,000, sixteen months before the bubble finally popped at over 5,000.

The decline of the Nasdaq from its peak was also far from linear or immediate. The index fell by more than a third in 10 weeks, then recovered two thirds of its losses before finally declining in a saw-tooth pattern to a 78 percent peak-to- trough loss in October 2002.

“The only thing we have to fear is fear itself”: Franklin D. Roosevelt, US President, 1933

There are four forces in the recent bursting of the “AI bubble” bubble:

1. New realism about what AI can and can’t do

OpenAI’s much-anticipated launch of GPT-5 in August turned out to be a dud, giving a slightly better user experience rather than the glimpse of artificial general intelligence that had been implied. Expectations got ahead of reality and the goalposts shifted. Capabilities that would have been greeted with astonishment 18 months ago were greeted with a shrug.

2. Infrastructure bottlenecks ahead

The rollout of AI has been faster than any previous technology, with ChatGPT getting 100 million users in two months and now on course for one billion weekly users by the end of the year. The basic foundations are in place and it is easy for consumers to use. Yet it will only pay off when enterprises can use it at scale, which depends on building – and financing – the most complex infrastructure ever created, comprising chips, data centres and energy.

3. Implementation depends on systems

A new technology itself is not enough. The hard yards are ahead in implementing it. That involves integrating it into well-governed enterprise systems that employees actually use. Evidence is still emerging of where the dollar and cents of value will come.

4. Human psychology: “that don’t impress me much”

There is an inevitable reaction to new technology reflected in the much-quoted Gartner hype cycle: innovation, inflated expectations, disillusionment, enlightenment and, finally, new productivity. In reality, these stages overlap and churn, with periods of overshoot followed by reality checks, after which the cycle resumes. Early humans probably had the same reaction to the wheel.

"The stock market has predicted nine of the last five recessions”: Paul Samuelson, economist, 1966

Vigilance is both prudent and a reminder of how hard it is to time the market.

Leading AI sceptic Gary Marcus predicted in 2022 that AI was “hitting a wall”. The WSJ, which published a report at the end of last week asking when the surge in AI spending will pay off, already ran a story called “Is the AI Boom Heading for a Bust?” in March and “Can AI Startups Outrun Dot-Com Bubble Comparisons?” last June.

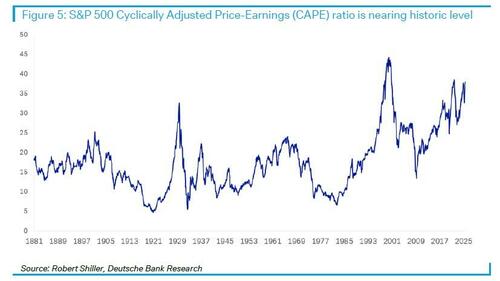

Others are asking similar questions as various indicators flash warning signals, like the Cyclically Adjusted Price-Earnings (CAPE) ratio for the S&P 500, which is approaching a near-historic 38, albeit below the 44 it hit in January 2000.

Bridgewater Associates founder Ray Dalio told the Financial Times in January that there was already a “bubble” similar to 1998 or 1999 while Greenlight Capital founder David Einhorn said on Friday that expenditure on AI infrastructure is “so

extreme” that there is a “reasonable chance that a tremendous amount of value destruction is going to come through this cycle”.

“Markets can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent”: John Maynard Keynes, economist

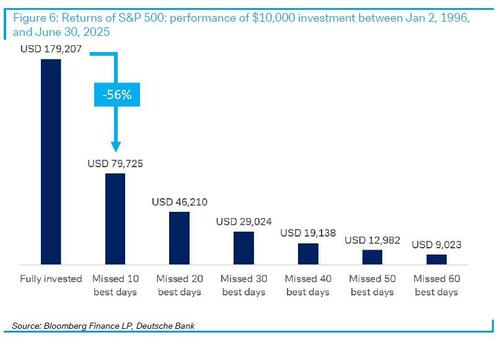

Timing the markets is notoriously hard. Evidence suggests that staying invested over a long time horizon seems to be the best way to capture the risk premium required to compensate equity investors for their risk.

Falls are rarely consistent as heightened emotions lead to volatility in both directions. If you had invested $10,000 at the start of 1996 it would have been worth more than $170,000 by the end of this June, but less than half as much if you’d missed the 10 best days and a quarter as much if you’d missed the 20 best days.

Indeed, five of the 10 best days from the start of 1996 to the end of June occurred within just one week of seven of the worst 10 days.

Stock prices have reached “what looks like a permanently high plateau”: Irving Fisher, economist, Oct 15, 1929, nine days before the Wall Street Crash

Earlier booms and busts followed similar patterns. The “railway mania” of the UK in the 1830s was derailed temporarily by the “Panic of 1837” emanating from the US, but then gathered steam once more en route to the bigger “collective hallucination” and crash of the 1840s. Likewise, the collapse of the “tronics” boom in 1962 was just a warmup for the meltdown in computing stocks at the end of the decade.

Radio was a 1920s analogue to the internet, spurring a race to invest in RCA and other technology companies more broadly, with companies such as General Electric, Dupont, Maytag, Chrysler and GM more than tripling between 1926 and 1929. The enthusiasm for the new technology was justified but premature, given that the network required a significant installed base of radios as well as broadcast networks and advertising to become commercially viable.

Bubbles have a variable lifespan, with the South Sea bubble blowing itself out in seven months while the dot-com bubble took five years to pop.

The question on everyone's lips: how long until the AI bubble, arguably the biggest bubble of all, does the same?

-

- *

Much more in the full JPM, Morgan Stanley, DB and Goldman notes referenced above, available to pro subs.