"You take the blue pill - the story ends, you wake up in your bed and believe whatever you want to believe. You take the red pill - you stay in Wonderland and I show you how deep the rabbit hole goes.”

- Morpheus, The Matrix

Some things in life are so deeply ingrained in our daily existence that we rarely stop to question them.

They are simply there, operating in the background, so fundamental to our existence that they feel as natural as the air we breathe.

We use them, rely on them, and move through the world assuming they are exactly as they should be.

For example, everyone is familiar with the phrase “Money makes the world go ‘round.”

This is rarely questioned and is rather accepted as self-evident.

Every day, you wake up, pay your bills, go to work, and check your bank account,—believing that you understand the system you operate within.

But have you ever stopped to ask yourself: What is money, really?

Not the textbook definition.

Not the economic theory you learned in school.

But the truth.

Money is everywhere. It dictates who eats and who starves, who rises and who falls. It builds empires and crushes civilizations.

It has fueled revolutions, financed wars, and controlled the fate of entire nations.

It is arguably the most powerful force on Earth, yet most people never stop to question its origins, its purpose, or its true nature.

You use money every single day. You earn it, you spend it, you save it. You trade your time and energy for it. It determines where you live, what you own, and the opportunities available to you.

It is so deeply embedded in your life that questioning it feels absurd—like questioning gravity or the air you breathe.

But have you ever wondered who decided what money is? Who, or what, gave it value? Or who controls it?

And more importantly—what if you have been playing a game where the rules were rigged before you were even born?

For those who are willing to look beyond the surface, the answers may be surprising.

But be warned: once you start asking the right questions, there is no turning back.

Money is one of the most universally recognized yet least examined aspects of human civilization.

It influences every facet of our lives, dictating our economic opportunities, shaping global trade, and acting as a central force in ways few ever consider.

Yet, despite its ubiquity, money remains a concept that is deeply misunderstood.

While we all use money, few of us ever stop to truly evaluate what it is, how it functions, and whether it works the way we assume it does.

The goal here is not to convince anyone of a specific perspective but to think critically about money—what it really represents and whether the reality matches what we have been taught.

If you were to stop someone on the street and ask them whether they knew what money was, they would almost certainly respond with a confident yes.

However, if you pressed them further and asked them to give a proper definition, the response might not come quite as quickly. The initial certainty would likely give way to hesitation as they search for an answer.

Were you to push a little harder or direct the question toward someone well-versed in finance or economic theory, the answers would likely become more structured.

At this level, people might begin describing the attributes associated with a strong form of money—qualities that make it function effectively as a medium of exchange, store of value, and unit of account.

If the conversation were to then go even further, those thinking critically about the question might move past the attributes of money and instead focus on what money actually does.

They might start discussing its role in facilitating trade, its function in settling debts, or its importance in economic transactions.

Yet, even if all of these points are accepted as true, the core of the question still remains: What “IS” it?

At its most fundamental level, a medium of exchange must be some “thing.” And what are tangible things made of?

Commodities.

By this reasoning, money—when stripped to its most basic form—is a commodity.

And commodities are made up of elements found on the Periodic Table. However, not just any commodity (or any element) can serve as money.

If a particular commodity is widely demanded and possesses some (or all) of the attributes that define strong money, then it ceases to be just a commodity and instead also transcends to become money itself.

At this point, it often becomes clear that money is the most marketable commodity, a good that serves as the final extinguisher of debt and that has been selected by free market forces over time.

This definition resonates with many who have studied the history of money and how different forms have evolved over time.

Taking this concept a step further, and recognizing that money is a commodity, and commodities are made up of elements from the Periodic Table, one might even evaluate the various elements to see which of them has the most attributes which would allow it to “ascend” to become money.

In doing so, one would realize that there in one commodity that has long been regarded as one of the strongest forms of money due to its unique set of attributes, which make it highly effective as a medium of exchange and store of value.

One of its most defining qualities is durability—unlike paper currency or other perishable goods, it does not corrode, tarnish, or degrade over time, ensuring that it retains its value across generations.

This durability allows it to function as a reliable form of wealth preservation, as it does not succumb to the forces of time or environmental conditions.

Another critical characteristic of this commodity is its divisibility.

Unlike other commodities, it can be melted down and divided into smaller units without losing its intrinsic value, allowing for transactions of varying sizes.

This makes it more practical as a medium of exchange compared to goods that cannot be easily broken down.

Additionally, it is fungible, meaning that each unit is identical to another unit of the same weight and purity. This interchangeability ensures that it can be exchanged without discrepancies in value, making it a highly efficient means of trade.

It is also prized for its portability.

Despite being a physical commodity, it possesses a high value-to-weight ratio, allowing individuals and institutions to transport significant amounts of wealth in a compact and convenient form.

This portability, combined with its recognizability, reinforces its status as a widely accepted and trusted form of money.

Across cultures and throughout history, it has been universally acknowledged as a store of value, and its distinct appearance and unique properties make it difficult to counterfeit.

Beyond these qualities, it also holds scarcity, a fundamental attribute that has preserved its value over time.

Its supply is naturally limited by the physical constraints of extraction and production.

This inherent scarcity prevents artificial inflation and ensures that it maintains its purchasing power over extended periods.

Lastly, its malleability adds to its utility, as it can be shaped into coins, bars, or intricate jewelry without losing its essential properties.

This adaptability makes it highly versatile, further cementing its place as one of the most effective and enduring forms of money.

We are, of course, talking about gold.

And indeed, throughout history, gold has embodied all the qualities of strong money—it is scarce, durable, divisible, portable, and widely recognized.

Its long-standing role in economic systems has led many to assert that it remains the ultimate form of money.

At this point, a show of hands might reveal broad agreement with this perspective.

But before reaching a final conclusion, it is worth pausing and asking: Has history always functioned under a free-market system?

More importantly, has money always been determined by the free market, or has another force been at play?

A common assumption that must be accepted when using the definition of money found above, is that markets operate freely, driven by voluntary exchange and competition.

But does this match with historical reality?

Has history always been characterized by a Free Market? Or, more importantly, has the world ever been truly governed by Free Market principles?

These questions are essential, but they require us to look at the world as it is, not as we wish it to be. Which leads to a broader discussion about the nature of money itself.

If we assume that money is simply a commodity chosen by free market forces, then we must reconcile this assumption with historical evidence.

And the simple fact is, there exists another perspective—one that challenges the traditional definition of money and forces us to reconsider whether money has ever been purely a market-driven phenomenon.

If history tells us anything, it is that the state has played a significant role in the shaping of history as a whole. The state has also played a significant role in the development of monetary systems.

So, if we are dealing with the world as it actually is, rather than how we want it to be, this simple fact cannot be ignored.

Throughout history, governments have issued various forms of fiat currency, not as a response to free market demand, but as a mechanism to facilitate trade, assert control, and support economic systems.

Ancient empires often minted coins made of base metals, stamping them with the images of rulers or state symbols, ensuring that their value was determined by decree rather than intrinsic worth.

These early monetary systems established a precedent where the state, rather than market forces, dictated what functioned as money.

During the Renaissance and beyond, paper banknotes emerged as a widespread monetary tool. Initially, these notes were backed by precious metals, reinforcing their legitimacy and trust.

However, over time, they gradually evolved into pure fiat money, entirely detached from any physical commodity.

This transformation allowed governments and central banks to exert greater control over monetary systems, as they were no longer constrained by finite reserves of gold or silver.

Colonial governments also played a significant role in monetary history, issuing promissory notes as a means of managing trade and economic activity.

These notes functioned as early forms of government-backed currency, representing an obligation rather than a tangible store of value.

As time progressed, fiat currencies became the dominant form of money, with modern states embracing national currencies such as the dollar, euro, and yen.

Today, fiat money exists in both physical and digital forms, serving as a testament to the continued evolution of state-sponsored monetary systems.

If we accept this historical reality, then we must ask: Is money truly a product of free markets, or has it always been shaped and defined by those in power?

Or put another way: Is money really the most marketable commodity that is chosen by the free-thinking individuals, or is it a powerful tool that is dictated by the King?

To answer these questions, it is first necessary to develop the skills needed to best understand one’s environment.

Situational Awareness is a fundamental skill that allows individuals to perceive, comprehend, and anticipate events in their surroundings, enabling them to make informed decisions and take effective action.

It consists of three essential components: first, the ability to perceive critical elements in the environment, such as people, objects, and unfolding events; second, the capacity to comprehend their meaning and potential impact; and third, the foresight to project future developments based on available information.

This skill is indispensable in high-stakes environments such as aviation, military operations, healthcare, and business, where the ability to recognize subtle cues and react accordingly can mean the difference between success and failure.

The same principle applies to portfolio allocation, where financial markets constantly shift, and a lack of awareness can lead to devastating losses.

Beyond professional fields, situational awareness plays a critical role in everyday life, enhancing personal safety, improving decision-making, and allowing individuals to navigate an ever-changing world effectively.

Without this skill, people risk being caught off guard, making poor choices, and suffering avoidable consequences.

Whether applied to personal security, financial decisions, or strategic thinking, situational awareness is a vital tool for optimizing outcomes in a world filled with uncertainty.

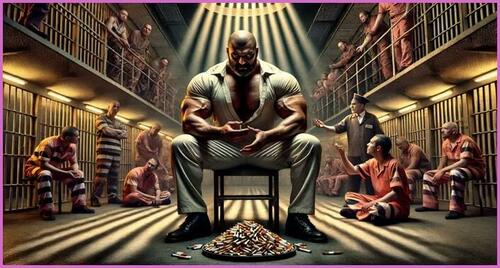

An example of applying situational awareness to our current topic at hand can be found in the below scenario.

As noted above; to optimize one’s circumstances, it is necessary to fully understand the environment in which one operates.

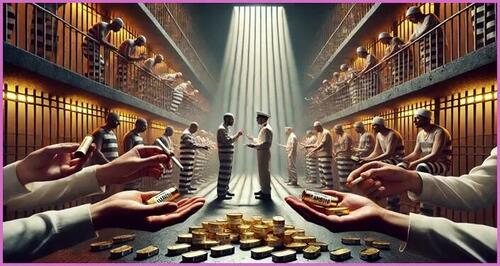

This principle is starkly illustrated in the closed ecosystem of prison economies, where traditional monetary systems do not exist.

In such environments, inmates rely on alternative forms of currency, selecting goods that are durable, widely accepted, and easily exchangeable.

For example, cigarettes have historically functioned as an effective currency behind bars.

They are in high demand, easily divisible for small transactions, and widely recognized as a unit of exchange.

Cigarettes can be traded for food, services, or other necessities, creating a barter economy that mirrors traditional financial systems.

Similarly, cans of sardines have emerged as a valuable commodity in some prison settings.

Their non-perishable nature, combined with their nutritional value, makes them a reliable store of wealth that retains its usefulness over time.

In the absence of officially sanctioned money, these items take on the characteristics of a medium of exchange, a store of value, and a unit of account—the very principles that define money itself.

This informal economy within prisons serves as a microcosm of broader monetary systems, demonstrating that money is not defined by government decree alone, but by what people collectively recognize as having value.

The lessons from these controlled environments underscore the importance of adaptability, resourcefulness, and understanding economic forces, no matter where one operates.

Its also important to understand that while both cigarettes and sardines have become popular forms of money found in controlled environments, they have not become so solely due to the marketability of their intrinsic qualities.

Consider a scenario within a prison economy, where sardines are widely accepted as currency. In this system, they serve as a medium of exchange, a store of value, and a unit of account—fulfilling all the necessary functions of money.

However, what happens when an inmate is transferred to a different facility, where the power dynamics have changed?

In this new prison, the dominant figure—the one who holds the most influence—hates sardines but loves cigarettes.

He has declared, by fiat, that cigarettes are now the required form of payment.

In such an environment, it no longer matters that sardines once held monetary value. The rules have changed, and the new authority figure has dictated a new system.

In this situation, would it make sense to insist that sardines are still money?

Or would the prisoner be forced to adapt to the new standard, recognizing that money is not determined by intrinsic qualities alone, but rather by the power structures that enforce its use?

Would you take it upon yourself to try and convince the dominant figure that he is wrong to demand cigarettes and that he should rely on free market principles rather than his own wants and desires?

This example raises a critical question: If given the choice, would we prefer a market-based form of money, determined organically by free exchange, or a system where money is dictated by a central authority that holds power over the participants?

Most people would instinctively lean toward the former, believing that free markets should determine the best form of money.

And because they believe that free markets would be better, they then believe that that is how markets developed throughout history.

However, there is a problem with this perspective—one that is rarely acknowledged.

Despite its widespread acceptance in economic textbooks and theoretical models, there is little historical evidence that large-scale barter and free exchange ever formed the foundation of monetary systems.

The assumption that markets naturally produce money without some form of imposed structure does not align with much of the historical record.

This challenges the idea that money evolved as a product of free markets and forces us to reconsider whether its origins are more closely tied to power, authority, and enforced rules rather than voluntary exchange.

Most people assume money has always been determined by free market forces. But history tells a different story—one where power, control, and coercion have shaped financial systems in ways few ever stop to consider.

So if money isn't what we think it is, what does that mean for everything else?

The conventional narrative about the origins of money suggests that it naturally evolved from barter systems, where individuals directly exchanged goods and services.

However, David Graeber, in his book Debt: The First 5,000 Years, challenges this assumption, arguing that there is little historical evidence to support the idea that barter was ever the primary foundation of economic systems.

Traditional economics textbooks often depict early societies as engaging in barter before money was introduced, but Graeber’s research suggests otherwise.

Instead, he argues that debt—not barter—was the foundation of economic exchange.

In ancient societies, trade was often based on credit systems, where individuals exchanged goods and services based on mutual trust and obligations rather than immediate physical payment.

These systems did not require money in the traditional sense but instead relied on social contracts and informal agreements.

Over time, these credit systems became formalized into structured debt, eventually leading to the emergence of money as an institutionalized means of settling obligations.

Graeber traces the evolution of debt through history, illustrating how it became deeply embedded in economic and political systems, often serving as a means of control rather than mere facilitation of trade.

He critiques the ways in which debt has been used to enforce social hierarchies, shaping power dynamics, and limiting individual autonomy.

By reframing the history of money around debt, Graeber sheds light on the underlying social mechanisms that govern economic systems—mechanisms that have long been overlooked or misunderstood.

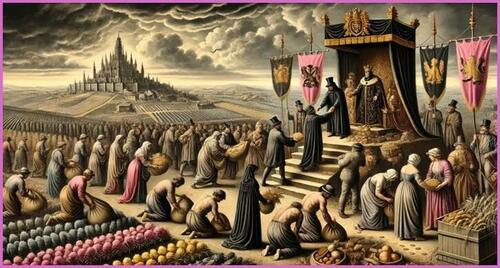

For example, it is well known that throughout history, rulers have exerted direct control over economic activity, using coercion, taxation, and structured debt to shape monetary systems.

In some cases, power was enforced through outright conscription, where the king would draft citizens into his army, demand their labor for infrastructure projects, or force them into servitude for state-building efforts.

There was little room for refusal—those who resisted often faced death or imprisonment.

In other cases, entire economies functioned under feudal systems, where peasants were forced to work the land, generating wealth that ultimately benefited the ruling class.

Under such systems, peasants were required to pay taxes “in kind,” meaning they surrendered a portion of their crops, livestock, or other goods directly to the monarchy.

After taxation, they were left with only what remained for their survival.

However, maintaining control through direct force has its limitations. It requires resources, effort, and an ever-present threat of violence.

A more efficient system would be one where control was maintained without constant enforcement—one where individuals voluntarily complied, believing they had agency in their economic decisions.

With that in mind, what if the king devised a system where, instead of demanding physical goods or direct labor, he issued a currency—a coin used to provision his kingdom?

What if, at the end of the season or the year, he required his citizens to pay back a portion of that currency as taxes?

Under this model, individuals would still be working to sustain the system, but instead of direct coercion, they would be compelled to participate in the economy to earn the issued currency.

The need to obtain coins to pay taxes would create demand for the currency itself, giving it value not because of intrinsic worth, but because it was the only way to satisfy obligations to the state.

In effect, this would achieve the same result as forced labor or direct taxation, but in a manner that was subtler, more efficient, and easier to manage. The system of control would still exist—but now, it would feel voluntary.

Before dismissing this idea as implausible, it is worth reflecting on the words of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who once observed: “None are more hopelessly enslaved than those who falsely believe they are free.”

The concept of debt as a mechanism of control is powerfully illustrated in the film The International, where Umberto Calvini, a leading global weapons manufacturer, explains to money laundering investigators why a major European bank is brokering Chinese small arms to third-world conflicts.

The investigators assume that the bank is simply profiting from war, but Calvini clarifies that the true objective is not to control the conflict itself, but to control the debt that war creates.

He states:

"The IBBC is a bank. Their objective isn't to control the conflict, it's to control the debt that the conflict produces.

You see, the real value of a conflict—the true value—is in the debt that it creates.

You control the debt, you control everything. You find this upsetting, yes? But this is the very essence of the banking industry, to make us all, whether we be nations or individuals, slaves to debt."

Calvini’s words underscore a chilling reality: war (and debt) is not just about land, resources, or ideology—it is a financial instrument.

By ensuring that governments and individuals remain indebted, financial institutions and those who control them can exert long-term influence over entire nations.

This shifts the focus from direct control through physical force to economic subjugation through perpetual debt cycles.

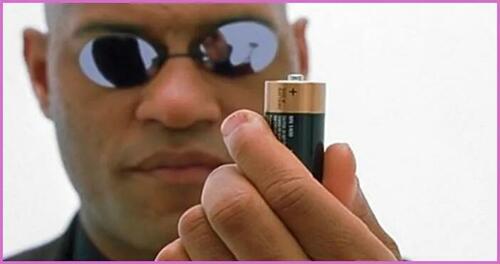

The idea that control extends beyond war and finance is further explored in the film The Matrix, where Morpheus reveals to Neo the unsettling truth about the world he lives in.

Neo, like everyone else, believes he exists in a reality where he makes his own choices.

But Morpheus exposes this as a fabricated illusion, designed to keep people enslaved without them realizing it.

When Neo asks what the Matrix is, Morpheus explains:

“The Matrix is a computer-generated dream world, built to keep people under control in order to change a human being into…this.”

At that moment, Morpheus holds up a battery, revealing the horrifying truth—humanity itself has been reduced to a power source for an unseen system.

In the context of financial systems, this analogy is striking.

Just as the machines in The Matrix extract energy from humans, modern economic structures extract wealth, labor, and productivity from individuals, often without their conscious awareness.

Most people never question the system they are born into, just as Neo never questioned his world—until he was forced to confront an uncomfortable truth.

By drawing these connections, it becomes clear that debt, economic control, and systemic influence function in ways that extend far beyond what most people perceive.

The question then becomes: If the world we live in operates under a system we never consented to, and one that most don’t even understand, how much of our reality is truly our own?

After exploring various perspectives, we arrive back at the fundamental question: What is money?

But before we attempt to answer, consider this—are you ready to take the Red Pill?

What if, echoing the words of both Umberto Calvini in The International and Morpheus in The Matrix, money is not merely a tool for exchange, nor simply a product of free-market evolution?

What if money has never been neutral, but rather, it has always been a mechanism of control?

If this is the case, then money is not just an economic instrument—it is the original Matrix.

It has existed for as long as power structures have, shaping civilizations, ensuring compliance, and maintaining hierarchies thousands of years before modern financial systems were even conceived.

It did not emerge organically from free markets, but rather, it was implemented and imposed by those in power.

If this idea seems radical, consider the analogy: money is a government-created construct, built to keep people under control in the same way that the Matrix enslaved humanity—turning them into batteries for an unseen system.

Morpheus' words about turning humans into a battery displays this concept perfectly.

But when Neo is confronted with this reality, his first reaction is horror and denial.

He recoils at the idea, rejecting it outright:

“I don’t believe it. It’s not possible.”

And perhaps, right now, you are having the same reaction.

Perhaps this notion seems too far-fetched—too extreme to be real.

And yet… can you be completely certain that it is wrong?

The challenge is not to accept or reject this idea outright. The challenge is to look at the world as it is, not as we want it to be.

If you can do that, then you must at least be willing to ask:

What if everything you thought you knew about money was an illusion?

But before we jump to a conclusion, let us take a closer look at some of the evidence. Evidence that we all have direct experience with.

From the moment we are born, we enter a controlled environment—one where registration is mandatory, where each individual is assigned an identification number.

This system is not referred to as a prison, but rather as a state or a country.

And yet, despite the different terminology, the structure bears an unsettling resemblance to an institution designed to manage and contain its inhabitants.

But unlike traditional prisons, this system is far more sophisticated. Here, you are not simply locked away—you are made to believe you are free.

You do not get to live in this system for free. There is a cost, a recurring obligation that must be met. They do not call these payments prison fees—they call them taxes.

Even though you are required to pay, you have little to no control over how the money is spent.

And to make matters worse, in order to obtain the money necessary to pay these taxes, you must first work within the system itself.

The economy is structured so that you must earn the state-sanctioned currency, which can then be used to pay the fees imposed on you.

There is no alternative. At least not one that does not involve the threat of imprisonment or violence.

But it does not stop there.

The system does not just demand your labor—it also encourages you to take on debt.

It presents you with shiny new products, new luxuries, new promises, enticing you to borrow more, ensuring that you remain tied to the system, dependent on its currency, and locked in a cycle that is nearly impossible to escape.

Unlike a physical prison, where the boundaries are visible, this system’s walls are invisible—and that is what makes them so effective.

You may believe you are free to move, but try leaving without the required documentation—a passport, a visa, or an approval.

Your movements are tracked, monitored, and restricted.

In some cases, certain "facilities"—whether by nation, regulation, or economic constraint—do not allow you to leave at all.

And yet, the most effective form of control is not force, but distraction.

The state provides news, entertainment, and endless engagement, ensuring that most people never even realize that the walls exist.

In fact, they are so skilled at this that the vast majority of individuals will never take a step back, never pause long enough to recognize the structure for what it truly is.

Now, some of you may be thinking: This is not really what money is. This is just that MMT mumbo jumbo. And others may believe that if this were true, the system would have collapsed already.

But remember, inevitable does not mean imminent. Systems do not crumble overnight. They endure for decades, centuries, even millennia before their inherent flaws bring them to their inevitable collapse.

So, after examining the evidence—after considering the nature of the system we exist within—have you changed your mind at all?

Do you see the pattern, but simply hate what it implies?

Understanding money as a mechanism of control does not mean outright rejecting the idea of free markets or market-based money.

Instead, it demands situational awareness—the ability to recognize and navigate the structures that shape financial systems, rather than blindly accepting them as immutable truths.

Free markets and commodity-based money may indeed be ideal, but reality tells a different story—one where monetary systems are largely centralized, manipulated, and designed to maintain power structures.

Acknowledging this reality is not about conceding defeat; it is about understanding the game you are playing so that you can engage with it on your own terms rather than being a passive participant in a system that was never built for your benefit.

The nature of money is inherently dualistic.

Sometimes, it is a market-chosen commodity, emerging organically from the free exchange of goods and services.

Other times, it is a state-imposed token, demanded by sovereign powers as the exclusive means to settle obligations like taxes.

And, in many instances, it is both at the same time—a hybrid of state control and market-driven value, existing within a framework that few ever stop to question.

None of this is meant to disparage free markets or the enduring role of gold.

On the contrary, history has shown time and time again that gold and sound money principles provide a more stable, trustworthy foundation for trade and wealth preservation.

If given the choice, most would prefer a system where markets, rather than governments, determine what functions as money.

But that is not the world we live in today.

To ignore this fact is to remain blind to the forces that shape global finance, leaving oneself vulnerable to the shifting tides of monetary policy, economic intervention, and centralized control.

Now more than ever, dogmatic beliefs about what money should be must not cloud our understanding of what money actually is.

In the years ahead, the ability to think critically, adapt, and remain aware of evolving financial realities will not just be valuable—it will likely be essential for financial survival.

Rather than clinging to an ideological framework that no longer aligns with reality, we must cultivate a mindset that allows us to see the world as it is, not as we wish it to be.

And situational awareness is the ultimate superpower in volatile markets—one that, if mastered, can not only help you survive, but to also thrive in the years to come.