Authored by Lance Roberts via RealInvestmentAdvice.com,

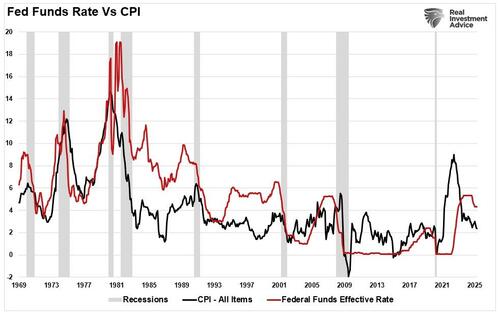

In 2023 and 2024, the Fed was under intense public and media scrutiny for calling the post-pandemic surge in inflation “transitory.” Critics argued that the Fed’s failure to anticipate the persistence and severity of rising prices undermined its credibility. Yet, with the benefit of hindsight and historical context, the Fed’s position wasn’t entirely misguided. Inflation proved temporary in a broader economic sense, and by 2025, the data confirmed a significant cooling of price pressures.

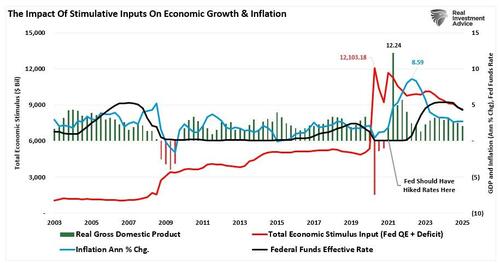

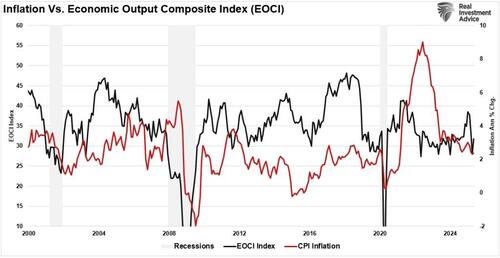

However, the Fed’s mistake wasn’t the “transitory” label—it was the Fed’s late response to raising interest rates and halting quantitative easing. As shown, the combined impact of the massive surge in the Government’s deficit spending (stimulus checks and infrastructure bills) and the Fed’s $120 billion monthly “quantitative easing” campaign caused a massive jump in economic growth and inflation. However, instead of cutting back on stimulus when the economy rebounded, the Fed’s mistake was keeping its “foot on the gas” for too long. These delays allowed the inflationary fire to burn hotter and longer than necessary, exacerbated by an overlooked driver: excessive government spending.

Despite the elevated levels of total economic stimulus, inflation and economic growth have subsided as the economy continues normalizing. However, to understand the Fed’s current policy risks, particularly in light of its recent warnings about tariffs, it’s essential to look back at past inflation spikes

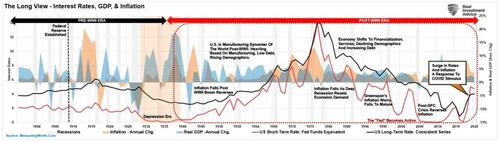

U.S. economic history offers several instructive examples of inflationary episodes and how they eventually resolved.

Compared to these episodes, the COVID-driven inflation surge stands out for its rapid onset and similarly swift decline. Prices surged due to supply chain disruptions, labor shortages, and historic stimulus. But by 2025, inflation is back to near-target levels. The duration of elevated inflation, from early 2021 through late 2023, was short by historical standards, and it faded as supply chains normalized and stimulus effects waned.

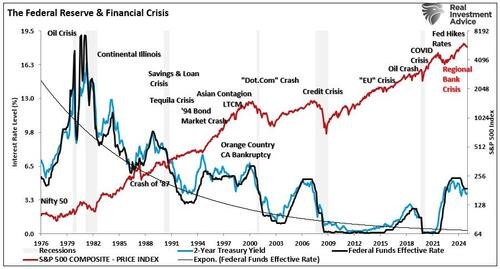

The historical shortcomings of the Fed’s actions, repeated policy mistakes, and flawed outlooks are clearly evident. The Fed hikes rates, creates an economic or credit-related event, and then cuts rates to fix it.

As such, investors should ask themselves why they are confident in the Fed’s current assessment of tariff-induced inflation risks.

At the June 18, 2025, press conference, Fed Chair Jerome Powell expressed concern that rising tariffs could reignite inflation. With trade policy becoming increasingly protectionist, particularly toward China and Mexico, the Fed is wary that tariffs could push up import prices and thus overall inflation. However, there’s an important distinction: inflation data from the last four months has shown no measurable impact from recent tariff actions. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) has remained stable or declined, while core inflation has softened. Meanwhile, job growth has slowed, and wage gains have moderated. All classic signs of a cooling economy.

This link between the economy and inflation is evident from the Economic Composite Index, which comprises nearly 100 hard and soft data points. Following the spike in economic activity post-pandemic, economic growth continues to decline. Given that inflation is solely a function of economic supply and demand, it is unsurprising that it continues to cool.

This raises a critical policy question: Is the Fed now over-compensating on the cautious side because of its past missteps with “transitory” inflation?

If so, the risk is that the Fed may once again make another policy mistake, as has repeatedly been the case in the past. After keeping rates too low for too long post-pandemic, policymakers might be too hesitant to cut rates, fearing another inflation flare-up that may never materialize. This fear-based approach risks undermining an already slowing economy.

Tariffs are designed to make foreign goods more expensive. However, supply chains and pricing are far more flexible in today’s globalized economy. If importers can shift production to tariff-free countries, renegotiate supplier contracts, or absorb costs to maintain market share, the inflationary effects of tariffs can be muted or even nonexistent. They are already doing this, as noted recently by CNN.

“The bonded warehouse route takes the opposite approach. Rather than mess with a good’s contents or move production elsewhere, businesses can import products from across the world without paying any tariffs when they enter the US — as long as they remain locked up in a special customs-regulated warehouse. Businesses can keep goods in these warehouses for up to five years without paying a tariff. They only pay the current tariff rate when they take goods out of storage. It’s a bet that tariff rates will go down in the short or medium term.”

Furthermore, companies are “reclassifying and redesigning” products to get lower tariff treatments.

“In other words, companies try to say their article or their good is something that gets low tariff treatment relative to what it might be, in essence. For example, Marvel successfully argued in court in 2003 that X-Men action figures are non-human toys (despite the premise of the franchise) rather than dolls, nearly halving their tax rate.” – NPR

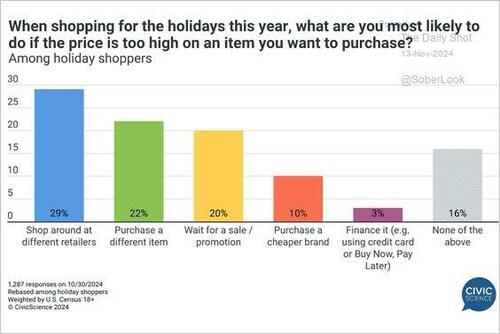

Lastly, as discussed in “Tariff Risk Isn’t Inflation,” economists always forget the importance of consumer choice. The only payee of tariffs is the producers. Consumers can purchase less, delay, or exclude certain products from their consumption. To wit:

“Today, globalization and technology give consumers vast choices in the products they buy. While instituting a tariff on a set of products from China may indeed raise the prices of those specific products, consumers have easy choices for substitution. A recent survey by Civic Science showed an excellent example of why tariffs won’t increase prices (always a function of supply and demand).”

Of course, if demand drops for products with tariffs, prices will fall, reducing inflationary pressures.

Recent economic data suggests exactly that. Despite new levies on Chinese electric vehicles and Mexican steel, consumer durables and core goods prices have not moved materially higher. Businesses appear to be adapting quickly, with many shifting sourcing to Vietnam, India, or reshoring certain elements of production.

This raises the danger of a policy mismatch: If the Fed waits for inflation that doesn’t arrive, it may keep real interest rates excessively high for too long, just as it kept them too low following the pandemic. The consequences could be severe:

If the Fed is fighting a phantom threat, as Alan Greenspan did in the late 90s, and tariff-driven inflation never arrives, it could inadvertently engineer a downturn. And much like in 2021 and 2022, this would be a policy failure driven not by bad data, but by misjudging the economic environment.,

The Fed’s credibility rests not on never being wrong, but on being adaptive and forward-looking. Inflation has cooled, wage growth has moderated, and economic momentum is slowing. Now is the time for the Fed to focus not on headline fears, but on real-time data.

If tariffs have not yet translated into price increases, and employment indicators suggest slack is growing, the Fed should not delay necessary rate cuts to defend its credibility. Doing so risks repeating the mistake it made during the pandemic: ignoring the lagging effects of previous decisions.

Cutting rates too late would be just as damaging as hiking them too slowly.

The media mocked the Fed’s “transitory” narrative, but inflation was short-lived in the grand scheme. What mattered more was how long the Fed waited to act. With tariffs yet to trigger a real inflationary response and the economy showing signs of deceleration, the greater risk may be inaction, not inflation.

Investors should be alert to the Fed’s tendency to overcorrect past mistakes. Just as policy stayed too loose after COVID, it may now stay too tight for too long in 2025. Recognizing that monetary policy must adapt, not just react, will be key for policymakers and market participants navigating the road ahead.

For more in-depth analysis and actionable investment strategies, visit RealInvestmentAdvice.com. Stay ahead of the markets with expert insights tailored to help you achieve your financial goals.