Authored by Peter Tchir via Academy Securities,

As I put pen to paper (or fingers to keypad), I can’t help but wonder if this is the hill that I want to die on?

There is so much uncertainty surrounding the banking developments last week. The only things that I know for certain are that SIVB ended the previous week at $284.39 and was halted before market open on Friday at $105.95 (and is supposedly much lower since). SI, not to be confused with SIVB, closed on February 28 at $13.91 and closed on March 10 at $2.53. That is what we know for certain. We also know that KRE, a $2.13 billion market cap S&P Regional Banking ETF, saw daily trading volume spike from an average of 8.7 million sharesto 97 million shares on Friday. In addition, its market cap dropped 16% last week (let’s call this the “mid bank” index). XLF, a “big financial” ETF, fell 8.5% last week on volume that “only” tripled, but it is exposed to financials other than “big banks”.

The prudent thing is to run away and wait for clarity. That is especially true when there is so much misinformation and even “FUD” (the term crypto people like to use when they disagree with someone’s negative crypto view) that it is almost imperative to stay away from this topic. However, I keep thinking of the phrase “The Lord Hates a Coward”, so let’s dive right in.

Before looking to the banks and the banking system, I feel it is absolutely necessary to highlight our focus on the “Disruptive Economy”. We believe that it played a large role in not just markets, but the broader economy for the past several years. We’ve used a “broad” definition of disruptive that encompassed some big tech, but also (and far more importantly) the entirety of public and private companies and their investors. In addition, we included crypto and crypto related businesses in that mix. That has led to several important conclusions (or at least thoughts) on our side:

Now that we’ve set the table with that recap of our views on disruption, we can move on to another table setting section.

I’ve been on both sides of highly controversial issues. I’m not always bullish, and if anything, I am more often than not bearish. It’s my nature, which is probably why I liked trading credit derivatives on junk bonds and indices.

I’ve also been comfortable taking the bull case. In fact, saying “buy Jefferies” in response to Steph Ruhle’s question (back when she was still on Bloomberg TV) created quite a soundbite for my independent research company. It actually turned out to be quite right (despite all the poorly thoughtout comparisons to MF Global).

More recently, at Academy, we championed credit by touting 2019 as the Year of the Debt Diet, having published a piece questioning the punishment that GE credit spreads were taking just a month or two before that.

Writing that GE piece feels eerily similar to what I’m about to embark on today. I can only hope that the results are as timely and as poignant. I’ve gotten plenty of things wrong, otherwise I’d be writing these missives from some exotic private island, but let’s do this and see where we come out!

I hate even writing those two words! It seems incredibly flammable. Like shouting fire in a crowded theater. I’m not even sure who I keep checking for over my shoulder when I write or say “bank runs”. Is it compliance? Is it the regulators? I don’t know, but this is a term that I rarely use because I think that it is shocking and dangerous, but I couldn’t figure out a better way to start the analysis of what is going on because this phrase is coming up with more frequency.

Banks are “strange” beasts. In some ways their business model is so simple (take deposits, lend money, and make the spread in between). But not only is that simplistic, it misses the key ingredient, leverage. You cannot take enough deposits and lend them out “one to one” to make a reasonable return.

VCSH, a 1 to 5-year corporate bond ETF, has a spread of about 110 bps. No one is buying a bank making 1%, so it needs leverage. Maybe the bank could take a lot of duration risk (I don’t know why it would, since banks learned a lot during the S&L crisis). But even with duration risk, banks aren’t an interesting thing without leverage!

So, we will talk about leverage, at least initially.

Banks have capital from several different sources at various levels of the capital structure.

A bank run is when depositors and lenders stop funding the bank, which normally occurs due to credit quality concerns!

When I think of a bank run, I think of a fear that the bank’s assets are not solid and would incur significant losses (if sold today or those losses would be realized over time as borrowers failed to pay the bank back). Accrual accounting, not held for sale, etc. are accounting provisions used to dampen volatility in asset prices on the bank’s balance sheet. There is a difference between a loan going down in price a bit because of rates (or overall market concern) and the likelihood of that loan getting paid off. During the GFC, it was apparent that massive amounts of mortgage debt were impaired and were never coming back. Again, I think that the regulators have done a very good job with CCAR (Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review). It incorporates many tough scenarios, but what I like most about it is that it is a “random” day, picked after the fact. Bank capital rules were almost exclusively quarterly and annual. There were massive quarter end trades done by banks. There were huge year-end trades done (especially between Asian and North American banks which had different year-ends) and these trades were less sensitive to certain annual measures. CCAR does a lot to capture the risk side of the balance sheet. It is designed so that “we” (collectively) can sleep at night “knowing” that banks are safe and won’t go through another GFC. Some of this may be questioned in light of recent events and disclosures, but I for one suspect that CCAR is serving its purpose, which is one reason why I’m heavily leaning towards this being isolated and not an industrywide issue.

On a cursory glance and from what I’ve read, there were some issues linked to the performance of “safe” (from a credit perspective) long-duration assets. From what I’ve seen so far, I’m surprised by the duration risk that was being run. I’m a big believer in “match funding” as much as possible. That tends to reduce NIM, but also greatly reduces risks, like the ones we seem to be seeing now. Sure, hindsight is 20/20, but that is something that I strongly believe in at all times.

Neither Moody’s nor S&P seemed to see much amiss at SIVB (no material rating action for years, until this past week). It seemed like business as usual, at least from a NRSRO (Nationally Recognized Statistical Ratings Organization) perspective.

I will attempt to demonstrate that this is a unique situation and is linked more to the types of depositors that these banks had than to anything that is reflective of a broad trend across the industry.

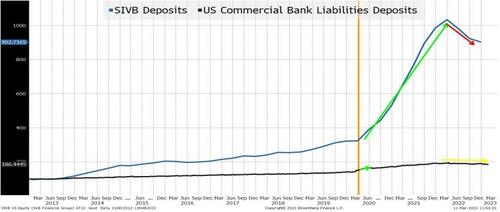

We start with deposits at the SIVB entities versus the entire banking system (note: SIVB deposit data is quarterly and last data point was from the end of 2022). You can see a small uptick in bank deposits during Covid relief (small as a percentage, but large in total dollars). SIVB saw their deposit levels more than triple (from $60 billion in March 2020, to a peak of almost $200 billion).

This chart highlights three important things:

The deposit growth seems reasonably correlated to value creation in the “disruptive” space (taking the liberty of using ARKK as a representative of that space). It was consistent with the narrative behind this entity.

Deposits, in my opinion, started declining because of the industry that this bank caters to, which had been incredibly successfully for decades, but was now burning cash and had less wealth. The initial phases of deposit decline had everything to do with the depositor base and little to do with their portfolio or any other “traditional” trigger.

It might also provide some insight into the sort of lending opportunities that were available at the time companies/individuals were making deposits (i.e., disruptive firms).

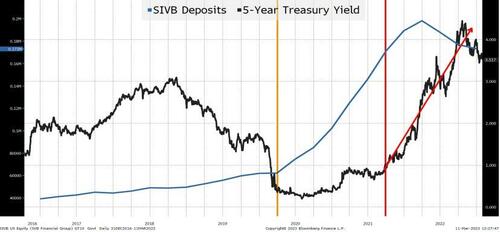

This chart is “problematic” in some ways as you can see the surge in deposits correspond to a period of time when the 5-year Treasury yield was less than 1%. Since deposit rates in the U.S. stayed positive (with very few exceptions) there was relatively little spread to be earned. Taking in huge deposits at a time when yields were very low can be problematic (and let’s not forget the need to leverage).

At this point, I have to admit that how they managed their portfolios also seemed to be contributing to the problem.

These institutions seemed to do two things that are now, in hindsight, problematic.

That has now contributed to their decline as the asset side is being called into question!

The two banks in question, while different, have some similarities that are unique to them.

Let’s get down to the theory here"

5 Circles of Bond Investor Hell

I see the situation as unique because:

I am stuck seeing this as far more unique than systemic, hence the recent selling is overdone!

The banking sector, even if I’m correct, will not get off scot-free.

I am fully aware of these two risks, but think that:

I saw a stat that SIVB has only about 3% of its deposits fully covered by the FDIC (very low compared to most banks). Presumably this is a bank for rich individuals and corporations.

This is the group that is in limbo and I don’t fully understand the next steps.

If you have $100,000,000 on deposit to meet your obligations, how much of that can you access?

In theory, as I understand this:

Some things in favor of SIVB’s valuations:

Understanding how much access to above FDIC limit deposits companies (and individuals) will have by Monday is crucial for the disruptive companies – more so than for other banks! Access (to at least a portion) is necessary for many to function. I fully expect there to be some contingencies allowing some % access, though I could be wrong.

I would not be shocked to see a “white knight” investor appear for the entire entity (possibly by Monday) because it makes a lot of the mess regarding the unsecured depositors go away (or at least more manageable).

In the early stages of the financial crisis, we saw various entities get absorbed with a nod (if not a gentle push) from the regulators, when only months before these transactions would have faced regulatory opposition.

The “easiest” and least painful way to value the assets might be via an acquisition by one large institution. I see two hurdles/questions facing that “dream”:

I’m convinced that the Fed learned one massive lesson from the GFC (we saw Europe do a semi-decent job with their own debt crisis) - DON’T LET CONFIDENCE IN THE BANKING SECTOR FAIL!!!!

Nothing else really matters. Financial institutions can write “living wills” until the cows come home, but if we get to that point, all bets are off.

If this is isolated (or even if it isn’t), regulators are supposed to be ring-fencing it in because the last thing they need is for “bank run” to become the word of the week. That is hard to walk back, so getting out in front of it is crucial.

Given how quickly they responded after Covid lockdowns (at warp speed relative to the almost plodding behavior back in 2007 and early 2008), there is hope.

I bet there will be a lot of green dots on Bloomberg terminals on Sunday night – I remember being there when $2 dollars/share came across as the price for Bear Stearns (and physically tapping my screen with my finger, thinking the 2 was a typo).

One thing many forget (or don’t know) about the JPM purchase of Bear was that it was accompanied by an immediate and non-contingent guarantee of Bear’s derivative book. Even if the equity deal didn’t consummate, the derivative book was JPM’s. No one ever really explained how that would work, and there wasn’t much (if any) formal guarantee language.

I also like big banks and small banks and am more scared of admitting that than I am of singing the original lyrics from this song – so yes, I’ve dragged myself to this hill and am going to stand my ground on it!

I did not have bank failure Sundays on my 2023 bingo card (but it does bring back memories)!