By Elwin de Groot, head of macro strategy at Rabobank

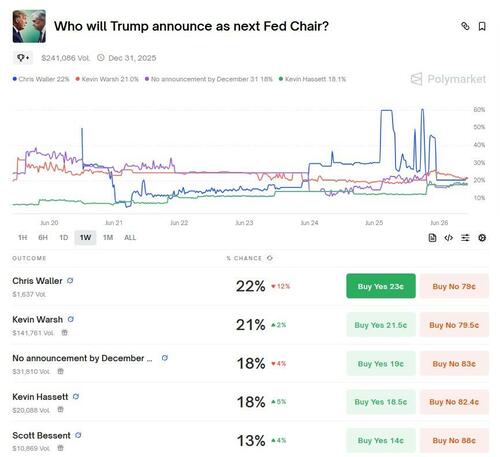

European bond yields inched up by several basis points whilst equity markets took a breather following the oil-price inspired rebound as the truce between Iran and Israel appeared to hold. Along with a 3bp decline in US Treasury yields, the dollar index slipped to its lowest level in more than three years, as President Trump is considering to announce his pick for the next Fed Chairman earlier than planned.

The Wall Street Journal writes this could be already in September or October, so well ahead of the official end to Powell’s term, which still has some eleven months to run. Even as Powell is likely to resist pressures to cut rates (quickly), an early nomination could undercut his ability to steer rates. Once his successor is known, markets will split their attention between Powell and the views of the next Fed chair. And whomever Trump picks, they are likely to be more dovish than Powell. Hence the distinct bend in the OIS forward curve in recent months with markets pricing in a higher probability of significant rate cuts over the course of 2026.

Other than that, a light data calendar on both sides of the Atlantic left market participants largely bound to the geopolitical news flow, in particular the NATO summit. To some extent, the latter even stole the show from the World Economic Forum, taking place in Tianjin, China this week.

After all the preparations and last-minute haggling between members, there was little doubt that the NATO summit was going to be successful. And, indeed, from a zoomed-out perspective, it was a success. Historic, even, by some standards. In its statement, NATO members reaffirmed their “[…] ironclad commitment to collective defence as enshrined in Article 5 of the Washington Treaty – that an attack on one is an attack on all.” Although Trump had earlier cast fresh doubts whether the US wholeheartedly support the Article, he later said that the US is with NATO “all the way”. And NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte went out of his way to underscore the US’ commitment in the press conference.

But the key achievement of the summit was the commitment by ‘Allies’ (a wording used instead of ‘NATO Members’ or ‘We’ to keep Spain on board), to ”invest 5% of GDP annually on core defence requirements as well as defence-and security-related spending by 2035 to ensure our individual and collective obligations […]” As expected this 5% of GDP should be broken down to at least 3.5% of GDP committed to ‘core defence requirements’ to meet NATO capability targets and up to 1.5% of GDP annually to, protect critical infrastructure, networks, ensure civil preparedness and resilience, unleash innovation, and strengthen the NATO defence industrial base.

As these broader goals had already been well-telegraphed, this explains the relatively muted reaction of European bond markets. But when you think of it, the relatively limited response in recent months to the swelling chorus of “more defence spending” is somewhat remarkable. Remember we had the significant jump in German Bund yields earlier in March when Germany announced its U-turn on defence and infrastructure spending and the interpretation of its debt-brake. But since that 50bp jump in only a few days, yields have come back down and are just 10bp higher than before that momentous decision.

And now – in essence – we have something that looks like a coordinated European-wide massive spending impulse (plus Canada etc.) lasting for many years. And bond investors seem to be shrugging. Yes, it will be phased-in, and yes, it remains to be seen whether members will stick to their plan. But not doing so seems the surest way of losing the US’s commitment to Article 5. No doubt there will be some shirking and foot-dragging, but the broader picture is that there is now a broad-based commitment. Of note: even Belgian Prime Minister De Wever, who had positioned himself as a ‘holdout’, had to swallow the bitter pill, as he acknowledged that 3.5% is a realistic figure and that NATO’s European member states must recognise that “our long break from history is over and we must take responsibility.” And Trump’s displeasure with the Spanish position indicates that we can be sure that peer pressure will be used to keep everyone in line.

So, again, moving from around 2% of GDP to at least 3.5% or even 5% structurally is not a small thing. To put it in perspective, the Eurozone’s structural (cyclically-adjusted) government balance, which is projected at roughly -3% for 2025 by the European Commission, has – since the Eurozone’s existence – never been higher than -0.8% (2018) and never lower than -5.1% (2010, in the midst of the sovereign debt crisis). In other words, this is going to require a lot of budgetary and financial acrobatics to make it work. Trying to find savings in other government spending items? Sure. Trying to raise some revenues here and there? Sure. But ultimately it would seem hard to avoid a significant increase in the deficit and hence issuance of government debt.

So, if you want to approach this from a more traditional viewpoint, then please look at the scenario’s we devised here. We basically assumed that in the coming years debt issuance will play a significant role, which is to be followed at some stage by fiscal consolidation. But the key message is also that to get sufficient ‘bang for the buck’, the design, execution and strategic patience will be the keys to success (or failure!) of these defense spending plans. That means leaving sufficient room for the European industrial complex to benefit from this spending, ensuring a coordinated approach (so that not everyone’s going to produce drones), make innovation with a significant ramp-up in defense R&D a key objective and ensure simplification of administrative processes, etc.

But, will there be sufficient (political) will in the future to consolidate after a debt binge? Or, if member states want to do this in a (budgetary) neutral way, how can they ensure that the economy doesn’t break down before they reach their strategic objective? Or how can Europe ensure that everyone meets their objective, and not just the countries with relatively sound debt-to-GDP ratios and the fiscal space (i.e. Germany)? So if you think that, somehow, this is not going to work then need to start thinking more out-of-the-box to ensure that funding will flow to the right sectors, that the financial burden is fairly distributed, and that these long-term security and defence objectives are ultimately reached without blowing up bond markets. There are no straightforward answers there, but the only suggestion I’d make is that at least we start thinking about this rather than just assuming that the current budgetary/financial framework we operate under can handle all this.