After a week of political chaos and a rollercoaster ride in French stocks, French President Emmanuel Macron is expected to appoint a new prime minister on Friday in a last-ditch effort to end more than a year of political paralysis and economic turmoil, marked by surging debt, rising poverty, and deeply divided parliament - all of which have pushed his second term to the brink of collapse.

To start the week, outgoing Prime Minister Sébastien Lecornu abruptly resigned on Monday, shortly after unveiling a new Cabinet, fueling a political crisis and turmoil in regional markets. The move triggered a surge in calls for Macron's resignation or new elections. In response to save face, Macron has vowed to name a successor by the end of today.

According to AFP News sources, Macron is expected to meet with leaders from the right-leaning National Rally (RN) and the radical left France Unbowed party at the presidential palace. Those sources confirmed that Macron will announce a new prime minister by evening.

Neither Macron nor Lecornu has offered any color or clues over who is in the running to be the next premier.

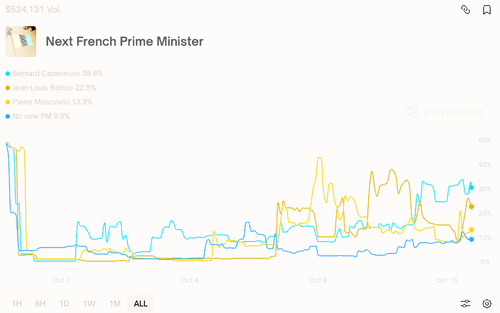

However, cryptocurrency-based prediction market Polymarket has socialist prime minister Bernard Cazeneuve at 30% odds, with Jean-Louis Borloo at 22.9%, and Pierre Moscovici at 13.3%.

Macron faces a massive fork in the road: appoint either a leftist or a technocratic leader to break the impasse of a deeply divided parliament. Either option will require compromises to avoid a no-confidence vote and could force the abandonment of Macron's unpopular pension reform.

Macron's 2024 snap election bet ultimately failed and produced a hung parliament and shattered his centrist bloc's dominance. Repeated government collapses, along with failed budget negotiations and internal rivalries, have left France's political system gridlocked and its economy in turmoil.

France's public debt has surged to 114% of GDP, while poverty reached 15.4% in 2023, marking the highest rate since records began - all suggest Macron is a horrible globalist leader. The European Commission and ratings agencies warned Paris to dial back spending and align with EU debt rules...

In markets, the CAC 40, the benchmark French stock market index, initially dropped 2% on the political turmoil earlier this week but has since clawed back those losses.

Marine Le Pen, a prominent figure on the nationalist right and a three-time presidential contender, said earlier this week that she would thwart all action by any new government and would "vote against everything."

Headline from FT...

We'll end the note with commentary from UBS analyst Simon Penn, who has been covering developments out of France all week.

Penn told clients earlier that political and economic turbulence facing France and the UK this year echoes Britain's 1970s struggles, an era defined by populist backlash, failed reform attempts...

In the 1970s, Britain went through a period of political turmoil and industrial unrest. The economic policies the government attempted to implement at the beginning of the decade were rejected by voters. It took almost a decade for the country to realise "there was no alternative". Today, both the French and British governments find themselves in circumstances where voters are rejecting their ideas and are instead being lured by populist policies that appear to have all the gain with none of the pain.

This is about political sequencing rather than direct economic parallels. The economies and markets of 2025 are very different from those of fifty or so years ago. But voter demands and political responses are similar. In 1979, new British Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher stood for election on a series of economic policies that were very similar to those proposed by the previous Conservative PM Edward Health in 1970. In between, the UK endured general strikes, a three-day week and an IMF bailout.

A very senior minister in that first Thatcher government once said that many of the economic policies introduced by Thatcher weren't actually original, mostly they were inspired by those of Heath nine years earlier. His point was that the country hadn't been ready for those policies earlier in the decade and needed to learn what the alternative route looked like before being willing to accept them.

What unites the 1970s UK to the UK of today, and also current French and British politics, is a statement and a question. In the wake of the Global Financial Crisis, then Luxembourg PM Jean-Claude Juncker said "We all know what to do, but we don't know how to get re-elected once we have done it." In 1974, having faced a backlash from voters, PM Heath asked the UK in the run up to a general election "Who governs Britain?" – the answer being a choice between government (his) or the unions (the allies of his Labour opponents). He lost and the country opted for a new Labour government. Margret Thatcher essentially asked the same question in 1979, and won. Applying Juncker's phrase to that period in the 1970s, to get elected afterwards voters have to experience the alternative for themselves.

President Macron is facing Juncker's statement and grappling with the decision as to whether to ask the country, as Heath did, and risk the consequences of the answer. What Macron needs his government to find is a policy route out of a near 114% debt/GDP ratio (on course for 125% in five years time); and a projected 5.4% of GDP budget deficit this year. The budget plans of his last three PM's have all been similar: departmental spending cuts, higher taxes, pension reform; and recently a proposal to abolish two public holidays.

Heath favoured free markets. He wanted to curb the power of the unions and end prior policies of state intervention in failing businesses and industries. During his first two years, from 1970 to 1972 he struggled to achieve his policy objectives and in 1972 he performed a U-turn. His Chancellor Anthony Barber cut taxes, increased spending and recommitted to assisting failing industry. By late 1973 Heath had been unable to appease the unions and in the midst of general strikes, the power workers walked out. The problems were exacerbated by the 1973 OPEC oil crisis and Heath ordered the country into a three-day week in an effort to reduce energy usage. In February 1974 he called an election, lost swathes of seats, failed to create a governing coalition, and eventually handed the administration over to a minority Labour government. Initially Labour were able to make some compromises with the unions, but as time passed the unions pushed their demands further and further. By the late 1970s the country was again on strike and had been forced to apply to the IMF for financial assistance.

What's interesting looking back at the UK towards the end of the 1970s was that two Labour governments, run by prime ministers that were sympathetic to unions, were unable to work with them. To overlay a present day term on the politics of 50 years ago, the public came to see that that the extreme demands of "populists" could not be satisfied.

The Conservative campaign of 1979 borrowed very heavily from Heath's manifesto of a decade earlier. It sought to curb union power, reduce taxes, reduce government borrowing, encourage free-markets and also self-reliance. Margret Thatcher had many other ideas and also employed aggressive marketing, but at the heart of her manifesto were the same policies Heath had attempted to deliver.

France and the UK face familiar political pressures then. For Macron the circumstances might be more acute than for Starmer, but even in the UK there is plenty of talk as to how he could be ousted and who could take over. A pivot by either Macron or Starmer, to either swing policy to placate voters with "easy" policy or in the case of France roll the dice with an election, could go very wrong.

What the IMF was to the UK in 1976, could become the ECB to France if voters reject Macron and the policies that are needed. The UK's next election isn't due until 2028, but the circumstances look similar. The unfortunate lesson from the UK in the 1970s is that the required policies are right there. It's just a question of time and pain until they are accepted.

. . .