Authored by William Anderson via The Mises Institute,

It has been The Project That Will Not Die.

What began as a California statewide voter referendum in 2008 to approve initial funding for a high-speed rail system between San Francisco and Los Angeles has become a financial black hole with no railroad to show for it.

Despite statements from Gov. Gavin Newsom that the system is fine, the Trump administration has announced it was pulling $4 billion from the project. In typical Donald Trump fashion, the president, on Truth Social, called it a “train to nowhere,” adding: “The Railroad we were promised still does not exist, and never will. This project was Severely Overpriced, Overregulated, and NEVER DELIVERED.”

Not to be outdone, California Gov. Gavin Newsom ordered the state to sue for the money, claiming that the Trump administration was breaking a legal contract. No doubt, a friendly federal judge will order the money reinstated, but one doubts that after appeals, the California High Speed Rail Authority will win.

Despite rhetoric to the contrary, The Donald is right on this one. From the project’s 2008 start to the present time, the idea of the state building a train that could go from San Francisco to LA in 2 hours and 40 minutes has never been a possibility, thanks to California’s unforgiving geography. Furthermore, even if California authorities were able to find even $100 billion more for this project, it could not be built as planned, and certainly not as promised.

In the annals of boondoggery, it is doubtful that any politician—even those that are especially venal and corrupt—ever sets out to create a boondoggle. While “boondoggle” is a word that probably is used too often (or maybe not often enough, if one really takes a hard look at government projects), it would seem that the word should have been created for the California bullet train project. The potential for financial losses is staggering, even by the high standards of financial chicanery that governments at all levels have been executing in the 21st century.

Joel Kotkin and Wendell Cox of The Spectator have written what should be the definitive article on this monstrosity, and their analysis is devastating. (You know, they state the facts of the case and the facts don’t need to be embellished in this situation.) In the beginning was the referendum:

When voters approved $9 billion for the plan in 2008, the California High-Speed Rail Authority estimated that it would cost $33 billion and start running by 2020 – and that was just for the San Joaquin Valley portion. The cost has since ballooned to $130 billion, and no stretch is operational.

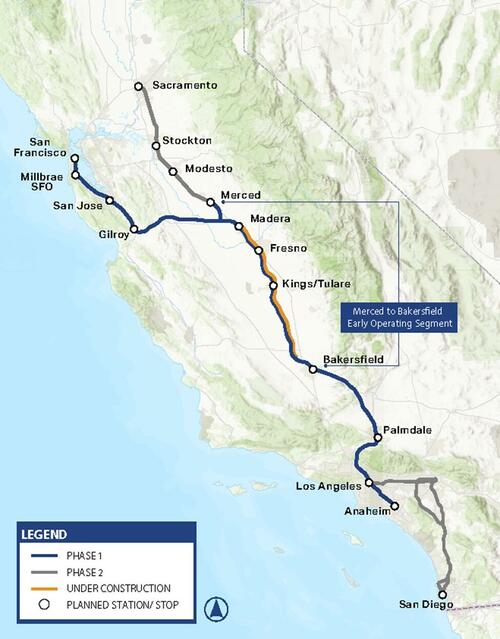

That should sink in. Seventeen years ago, voters approved a plan to build something that would supposedly be done 12 years later. Today, the earliest projection of finishing a truncated line in the Central Valley—a 171 mile stretch between Bakersfield and Merced—is 2030 to 2033, and this project has not met a single deadline.

As I noted in a previous article last spring, construction of the line has been occurring on that Central Valley stretch, but even if this part of the project is ever finished, there are still another 300-plus miles to go, and much of that will have to go through a number of California’s many mountain ranges. In the northern portion, a 1.6-mile and another 13-mile tunnel through Pacheco Pass would be required, and neither tunnel is in even preliminary planning stages.

In the southern portion, once the train goes south of Bakersfield, it hits the Tehachapi Mountains, where the current freight line goes over a pass at 4,000 feet after passing through the famous Tehachapi Loop. While a slow-moving diesel-electric train can make the climb, going over this uplift is not conducive to electrified high-speed passenger rail, which would require extensive tunneling through this mountain range that has peaks almost 8,000 feet high. Like the planned Pacheco Pass tunnels, the proposed dig through the Tehachapi exists only in the abstract.

The last leg goes through the San Gabriel Mountains, which will require extensive tunneling and grading before finally coming into Los Angeles proper. At this point, one understands the enormous task that would be ahead should the Central Valley portion ever be finished, as this portion is the easiest part of the entire project. Write Kotkin and Cox:

Worse yet, the biggest financial obstacles loom ahead. Much of what has been built has been easier-to-build flat valley land. Far more expensive tasks lie ahead, such as building 30 miles of tunnels through the San Gabriel Mountains and nearly 15 miles of rails traversing Pacheco Pass. One stretch must climb from approximately 400 feet above sea level in Bakersfield to about 4,100 feet. If the costs of the Los Angeles and San Francisco extensions replicate the experience of the much-easier Bakersfield-to-Merced segment, our analysis suggests a final cost that could be nearly double present projection: about $250 billion.

Most likely, even $250 billion might be an underestimation, and there is no way that the state can fund such a gargantuan project by itself, given that this coming year’s California state budget itself is $321 billion. Kotkin and Cox, again:

With no prospect of private investment, it’s hard to see where the money will come from. This puts Governor (and aspiring presidential candidate) Newsom in a tight spot, forcing him to choose between funding the money-mad train and balancing his budget, or addressing critical progressive priorities such as public-employee pensions and free healthcare for the state’s estimated 2.5 million undocumented immigrants.

Despite the “finish it at all costs” rhetoric coming from Sacramento and the Democrats in California’s Congressional delegation, the bullet train project will never be finished in its entirety, but California’s Democrats will do everything they can to finish the present 171-mile project. If not, every Republican running for office in the state will show photos of unfinished bridges and viaducts and point out that California taxpayers will be paying for money borrowed through the bond issues into perpetuity.

If this stretch of the railroad is finished, it will probably be the least ridden high-speed line in the world and will be the subject of jokes. However, one can imagine that whoever is in the governor’s seat will declare victory, not just because the line is finished, but also because they will have spent billions of dollars in the process, enriching contractors, unions, and anyone else standing under the money spigot.

At the end of the classic 1935 movie “Little Caesar,” Rico the gangster (played by the incomparable Edward G. Robinson) is gunned down by Police Sergeant Flaherty, his last words being, “Mother O’ Mercy, is this the end of Rico?” One can only hope that Trump has played the role of Flaherty in putting the California Bullet Train out of its misery.

California politicians have shown themselves capable of mind-bending foolishness, but nothing in the history of foolishness in this state comes close to this railroad. If nothing else, however, perhaps the steel and concrete that makes up the “bullet train” can stand as a warning to future governors and presidents that economic laws exist for a reason, and that those that bend or break them will have to deal with the consequences.