Authored by Robert Burrows via BondVigilantes.com,

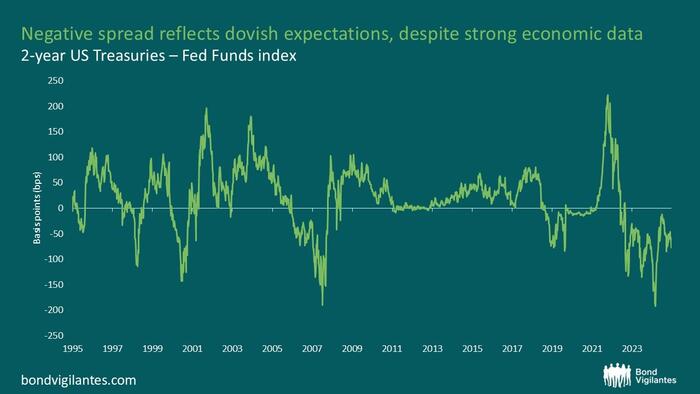

Markets are once again high on ‘hopium’. Despite a still-strong labour market, sticky inflation, and an economy that refuses to roll over, rate cut bets have surged back into vogue. The Federal Reserve might be saying “higher for longer,” but investors are dancing to a different beat.

Why is the market so convinced cuts are coming when the data tells a different story?

Let’s start with the basics. The US economy continues to defy gravity:

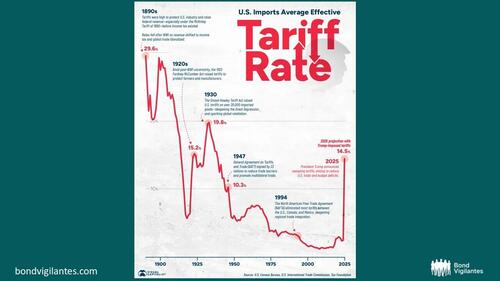

Source: Visual capitalist, US Census Bureau, US International Trade Commission, Tax foundation

And yet, futures markets are entertaining the idea of 150 basis points in cuts by the end of 2026. You’d be forgiven for thinking a recession was imminent, but the data simply doesn’t support it. There is no clear and present danger requiring immediate monetary easing. It appears as though an asymmetry is creeping into the market.

Source: Bloomberg

A caveat on the impact of this monumental change in tariffs is that they will impact both inflation and growth going forward, muddying the waters and making the Fed’s job even more challenging.

So why the divergence?

The Fed’s traditional response function (think Taylor rule) is simple: respond to inflation and unemployment.

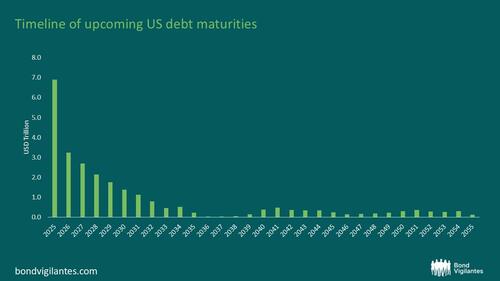

But what if that framework is breaking down? What if the central bank is now facing a third variable it can’t ignore: government debt sustainability?

Public debt-to-GDP has ballooned. Servicing costs are rising fast. Higher rates have doubled (or more) the cost of new borrowing.

The question is no longer just “is inflation too high?” or “is growth slowing?”, it’s becoming: “can we afford to keep rates this high?”

There’s a growing theory that debt sustainability is starting to influence monetary policy, if not overtly, then tacitly:

Source: Bloomberg

While the Fed remains technically independent, the economic reality is putting it in a box. Rate hikes were politically feasible when inflation was the villain, but as that narrative softens, so too does the Fed’s room to manoeuvre.

This raises a disturbing possibility: maybe the market isn’t mispricing rate cuts, maybe it is betting on fiscal dominance and a more politicised Fed. That is, central banks may eventually bow to the needs of the government balance sheet and the wants of an incumbent government, rather than to strict macro fundamentals.

What The Fed does next may no longer be about data alone. It may be about debt. If so, we’re entering a new regime: one where traditional models of inflation and employment lose their predictive power, and monetary policy becomes a servant, not a master.

So when the market prices in cuts against a backdrop of strong economic data, maybe it’s not madness. Maybe it’s a grim kind of foresight: the Fed is trapped, and the old playbook has been thrown out.

One thing’s for sure: if the Fed is no longer fighting inflation, but instead grappling with the math of Treasury auctions, then it’s not just rates that need re-pricing, it’s the entire framework we’ve relied on to understand monetary policy for the last 40 years.