Authored by Lance Roberts via RealInvestmentAdvice.com,

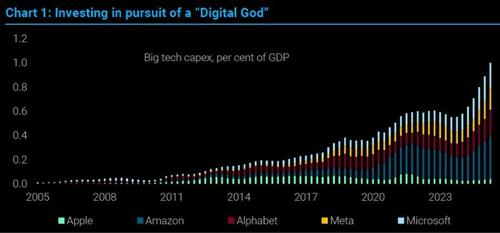

If you want to understand the engine under this market’s hood, follow the capital. A recent article by Michael Cembalest frames today’s AI boom as a “vendor-financing circle.” This circle occurs when capital raised by one set of companies (via stock, convertibles, or bonds) is recycled into other companies, and so on. In today’s market, that is where AI-related companies are raising capital to make massive AI capex investments, which become revenue for a handful of infrastructure suppliers (GPUs, networking, power, and data centers). Those reported revenues, in turn, help justify still more capital raises, higher valuations, and even bigger build-outs. It looks and feels like reflexivity in real time.

You can see the loop in the tape. With sequential growth powered by AI demand, Nvidia’s data-center cycle has produced staggering top-line figures: $30B for Q2 FY2025 and $46.7B for Q2 FY2026. Those dollars don’t appear out of thin air; they are funded by hyperscalers and “neoclouds” expanding footprints at breakneck speed.

Meanwhile, capital formation downstream has accelerated. Citigroup projects AI infrastructure outlays to reach roughly $490B by 2026 and $2.8T by 2029.

Oracle’s $18B bond sale, a jumbo deal, was explicitly tied to building AI cloud capacity for large customers. And OpenAI’s “Stargate” initiative targets a stunning $500B to deploy ~10 GW of compute across sites, with partners and suppliers intertwined through equity stakes, long-dated supply agreements, and chip-leasing constructs. When suppliers invest in customers who then pre-order supplier hardware, you’re not just seeing demand but circular demand.

For example, Oracle doesn’t have the money to pay for this spending surge, which is projected to last well into the 2030s (This also assumes that there is NO RECESSION between now and then). While vendor financing with cash from operations is one thing, vendor financing with cash from debt is something totally different. As Cembalest noted, we have now evolved into a “circular economy” of AI, where growth depends on a narrow group of companies. As he noted:

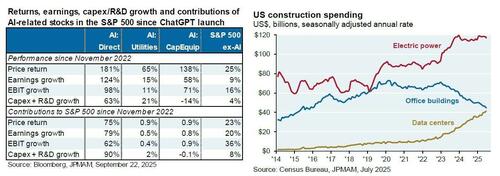

“I think this is well understood, but just to reinforce the point: AI related stocks (1) have accounted for 75% of S&P 500 returns, 80% of earnings growth and 90% of capital spending growth since ChatGPT launched in November 2022. AI is showing up other places as well. Data centers are eclipsing office construction spending and are coming under increased scrutiny for their impact on power grids and rising electricity prices.”

But here is his real eye-opening statement:

“Other recent AI news: Oracle’s stock jumped by 25% after being promised $60 billion a year from OpenAI, an amount of money OpenAI doesn’t earn yet, to provide cloud computing facilities that Oracle hasn’t built yet, and which will require 4.5 GW of power (the equivalent of 2.25 Hoover Dams or four nuclear plants), as well as increased borrowing by Oracle whose debt to equity ratio is already 500% compared to 50% for Amazon, 30% for Microsoft and even less at Meta and Google. In other words, the tech capital cycle may be about to change.”

This pattern has historical rhyme. During the late-1990s telecom boom, equipment makers extended aggressive credit (“vendor financing”) to carriers, effectively funding the purchase orders that produced the vendors’ reported revenues. By mid-2001, the Wall Street Journal tallied at least $25.6B of such loans across major vendors; for one cohort, that financing equaled 123% of combined pretax earnings in 1999. Vendors wrote down receivables when customers defaulted, and the virtuous loop snapped.

The takeaway isn’t that today’s AI spend is fake; the ecosystem itself reflexively finances some portion of revenue. While that completely supports the market while the “music plays,” it becomes problematic if cash returns lag capex for too long, power and supply constraints slow utilization, or financing windows narrow.

Is AI a bubble? Maybe.

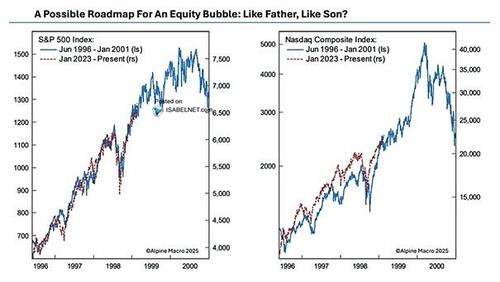

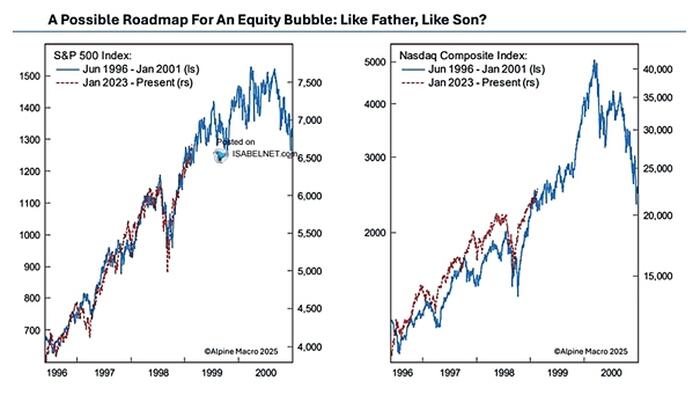

Every bubble has a story at its core. In 1999, that story was the internet: a transformational technology that would reshape commerce, communications, and culture. Investors saw the future, bid prices into the stratosphere, and assumed profits would inevitably follow. In 2025, the story is artificial intelligence, which carries the same irresistible promise of reshaping industries, creating productivity booms, and unlocking new frontiers. The parallels are hard to miss, along with the current price action.

Like the dot-com era, today’s market is being driven by breathtaking growth assumptions. Back then, Cisco traded north of 100x earnings on the belief it was selling the “backbone of the internet.” Pets.com and Webvan raised hundreds of millions, only to collapse when business models proved unsustainable. The psychology, then and now, is driven by the “fear of missing out.” Investors rush in because the narrative is too powerful to ignore: However, “if AI changes everything, you can’t afford not to own it.“

But while the similarities are striking, the differences are equally significant. Unlike the dot-com darlings of the 1990s, today’s AI leaders are not pre-revenue companies burning cash with no path to profitability. Nvidia generates tens of billions in quarterly revenue from its GPU dominance. Microsoft, Amazon, and Alphabet have deep operating businesses producing free cash flow to fund their AI bets. These are not speculative shell companies; they are some of history’s largest, most profitable corporations.

That distinction matters. In the late ’90s, investors piled capital into companies with no earnings or customers. Today, investors are bidding up firms with massive revenues, entrenched customer bases, and operating leverage. The risk, however, is that investors are again extrapolating linear revenue growth into the future without considering bottlenecks, power constraints, monetization limits, and slowing marginal returns on AI spend.

So while today’s AI ecosystem is more grounded than the dot-com startups of 1999, the underlying behavior is the same: valuations are being stretched on the assumption that a revolutionary technology will deliver exponential profits.

History reminds us that transformative technologies often succeed over decades, but the first wave of companies and their investors rarely capture the full promise implied in their stock prices.

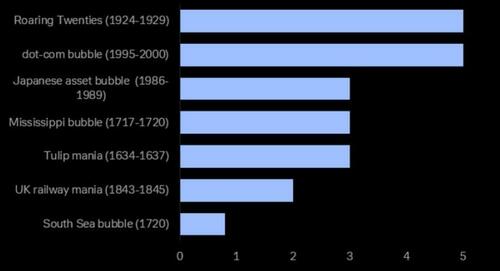

Timing is the cruel part. As shown above, is this Alan Greenspan’s “irrational exuberance” moment in December 1996? Or, are we much later in the cycle? Honestly, I have no idea. But in 1996, the Nasdaq peaked more than three years later, suggesting that amid the “inflation of a bubble,” inflation can last longer than seems logical. We see that through all previous bubbles in history.

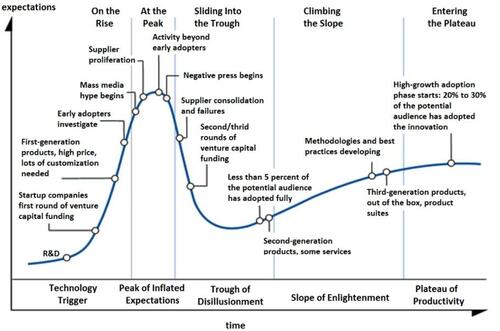

The critical issue for investors, both then and now, was that many were “right” about the Dot.com bubble. However, they were so early in their warnings that they were wrong in their portfolios. The same warning applies currently. Is there a bubble in AI? Maybe. But, I would even suggest that it is pretty likely. As investors, we must realize that during the “inflation” phase of the bubble, there is a lot of money to be made, but the cycle will eventually end.

That’s why fighting parabolic moves can be so problematic. As Peter Lynch once stated:

“Far more money has been lost by investors preparing for corrections, or trying to anticipate corrections, than has been lost in the corrections themselves.”

Read that again.

We are likely closer to a top than not, but that top could be months, quarters, or even one or two years away. That is why the better frame for investors to consider is “cycle math.” Focus on liquidity, policy, indexation, and corporate incentives, as they can extend manias far beyond fundamental comfort. However, eventually, those cycles begin to reverse, and what previously ended speculative bubbles begin to “rhyme.”

From 2000 to 2002, the telecom sector unwind delivered all of the above from defaults, receivable write-offs, and serial guidance cuts. Replace “fiber overbuild” with “compute and power overbuild,” and you have a credible left-tail scenario if demand monetization trails supply for too long. Ratings agencies and sell-side shops have noticed, flagging the leverage and power constraints embedded in the current build cycle, even as they acknowledge substantial real use cases.

Today, it is the same, but in a different form. As Roger McNamee recently wrote for The Guardian:

“Investors have assumed that every major US player in [large language models (“LLMs”)] will be a winner. This assumption is essential, as the monopolies that power big tech – such as Microsoft’s Office suite, Google Search, Gmail, and Docs, and Meta’s Facebook – are, without exception, approaching the end of their useful lives. The vast majority of customers believe that these products have gotten worse – and made users less productive – over the past decade or more. Each big tech company needs a global monopoly in AI to sustain their success and market value. They are not all going to get one.

The former General Electric CEO Jack Welch made famous the notion that only two players can be profitable in a competitive industry. Below the top two, it is a struggle to survive. That means that at least three, and perhaps more, of the current players will be forced to write off their investments in LLMs. Each of the big tech companies has invested in the range of $100bn through this year, and by next year that number could easily double. If LLM technology does not improve rapidly, their corporate customers will also face write-offs.

The day may come sooner than many expect when shareholders, directors and executives will demand evidence that the massive investment in LLM technology will generate an adequate return for them. The answer will be no for many, if not most, players, and the reckoning will [be] ugly for everyone.“

Such reminds me of Charles Kindleberger’s old line:

“If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.”

Critically, I am not suggesting that the AI bubble is about to burst tomorrow. We have many of those particular stocks in our portfolios, from Google to Meta to Nvidia and others. Furthermore, my discussion here is not intended to be a timing tool but rather a budgeting tool. Don’t expect the current market to underwrite infinite carry from a finite financing window. That mindset kept investors alive in 1999–2002 and again in 2007–2009. It applies again in 2025.

Let me conclude by stating that my intention is not to dunk on innovation; it’s to manage risk amid it. The practical playbook in bubbles is more carpentry than heroics.

First, separate plumbing from promises. Infrastructure winners can post extraordinary revenue growth if the financing loop remains open. That’s tradable momentum but not the same as durable, end-customer ROI. In your underwriting, prioritize evidence of cash demand (contracted workloads with measurable payback) over capital demand (pre-buys and option-like contracts funded by equity or fresh debt). Until the monetization bridge is built, capex dependence is a risk factor, not a moat.

Second, let prices do the heavy lifting. When leadership is this extended, mean-reversion is a feature, not a bug. Use predefined rebalancing bands to trim exposure into vertical rallies and add on resets to rising 50/100-DMAs instead of chasing exhaustion gaps. That keeps you involved (because bubbles can run) while turning volatility into a source of discipline rather than damage.

Third, demand balance-sheet realism. In the late ’90s, vendor financing and receivables quality were the tell. Watch interest coverage after new bond deals, capex as a share of operating cash flow, and disclosure around take-or-pay or utilization guarantees. If the ecosystem is cross-subsidizing itself (supplier invests in the customer who pre-orders the supplier’s gear), discount the apparent “visibility.” The more circular the revenue, the more fragile the flywheel when financing costs rise. Recent deals around Stargate and supplier co-investments are a case in point.

Fourth, think in barbells and play defense in the middle. On one end, maintain a measured exposure to proven cash generators that genuinely benefit from AI (unit-level margins, network effects, or distribution that converts AI into pricing power). On the other hand, hold high-quality ballast, short-duration Treasuries, or cash equivalents, to fund drawdowns and keep optionality. In between, be choosy with capital-intensive stories where the cash-in date sits far beyond the cash-out date. As the Dallas Fed and Goldman work suggests, productivity gains likely build over years—not quarters—so leave yourself time.

Finally, accept that you won’t nail the top. That’s okay. Successful navigation is less about calling a date and more about insisting on process: valuation awareness, position sizing, staged entries/exits, and the humility to let price action confirm your thesis. Bubbles end the same way, financing tightens, a few high-profile misses flip psychology, and cash becomes king. Have some.

Trade accordingly.