By Stefan Koopman of Rabobank

As the group stage of the Euros reaches its zenith, let’s take a look at the European economic game plan for the coming months. Since the beginning of the year, the prevailing view has been that the services sector is poised to score some goals, bolstered by an increase in real wages and a partial recovery from 2022’s significant terms of trade shock. This would be more than enough to counterbalance the manufacturing sector’s losing streak. This has led to an increasingly divergent trend among nations, with Italy and Spain on a winning run, France mostly drawing, and Germany scoring some own goals but eventually finding its footing. This scenario, coupled with the potential for improved European strategies and tactics as outlined in the Letta and Draghi reports, has been quite advantageous for European risk assets this year.

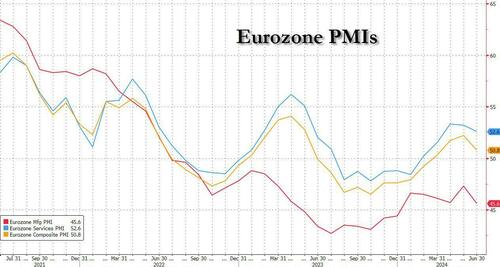

However, as we advance into the year, European economies struggle to find their form. The interest rate shock is still filtering through, coupled with a negative fiscal impulse (i.e. budget deficits are sizable, but not adding to growth). Even though GDP surprised in the first quarter, it was largely driven by net exports instead of domestic demand. The June composite PMI, released last Friday, indeed signaled a slow jog into the second half of the year. In Germany, manufacturing remains the Achilles’ heel, with the PMI diving to 43.4. The services sector is pushing forward with a modest 53.5, although this fell short of expectations too. In France, the private sector stumbled, with a downturn in new orders leading to a contraction in business activity to 48.2. This decline looks to have been compounded by faltering confidence amid France’s electoral uncertainty.

Looking forward, the pundits will tell you that Europe’s economic outlook remains constructive, with expectations that consumer spending will eventually drive the economy towards a more robust growth trajectory. However, the PMIs published last Friday highlight that progress towards such a ‘steady state’ may not be linear. We too anticipate the Eurozone economy to grow by 0.7% this year and 1.4% in 2025, but keep an eye on the potential offside trap of political uncertainties in France. A strong showing of the far-right could be a game-changer, making prospects for significant and much deeper European integration seem like a long shot.

The UK’s PMI softened, marking the private sector’s slowest expansion since November with a reading of 51.7, akin to England’s so-so performance this Euros. Although we suspect that pandemic-related seasonal adjustment problems are still an issue, creating ‘booms’ in the spring and ‘busts’ in summer and autumn, the survey attributes the decline to a temporary halt in business spending amidst the election. Meanwhile, inflationary pressures resurged in June, propelled by a significant rise in transport costs due to global shipping constraints. In the services sector, wages continue to be the primary inflation driver. Prices charged across the private sector consequently rose to a four-month high in June, leaving the Bank of England with a complex play to analyze.

Meanwhile, the UK election remains a bit of a non-event. Coupled with the instability in France, it explains why the pound has been strengthening against the euro. It still seems that Keir Starmer will become the next Prime Minister. All the UK’s issues at hand, excluding those related to the England national team, are predominantly associated with the Conservative Party, which has been in power for the last 14 years. This created space for the Reform Party and a split within the right-wing vote. Had the Conservatives been able to hold the right, they might have presented a stronger challenge to Labour.

The question markets will immediately focus on July 4th: what will be the size of the potential majority? Some speculate that a Labour party with a 200-seat majority would wield much more power than with a 100-seat majority. However, it’s important to remember that there is no such thing as a ‘supermajority’ in this context. Practically, there is little difference between winning a 100- or a 200-seat majority. In fact, we would argue the opposite: larger majorities tend to face more significant rebellions and political uncertainty simply because they have the numbers to do so. We remain constructive on the UK’s outlook post-election, but also note that the Labour manifesto appears better at diagnosing the UK’s underlying problems than at presenting clear policy proposals and spending plans to address them.

President Macron’s move to call for early elections could potentially shift power to the far-right in France. The first round of the election will be held next Sunday and will be pivotal for European assets. As the election nears, polls fluctuate but hint at Marine Le Pen’s party emerging as France’s largest, yet possibly shy of a majority. How these polls play out as we approach Sunday will sway sentiment on the euro and French, or even European, assets. Given that the euro weakened when Macron announced the snap election, an expected Le Pen majority could further weigh on it.