President Trump is positioning himself as a tough trade negotiator, peacemaker and champion for U.S. workers during the first six months of his second term.

There is a common thread stitching them together: precious metals, minerals and other valuable stuff that can be pulled from the earth.

Whether it is a U.S.-facilitated peace deal in Africa or the latest trade deal, hardly a day goes by without Mr. Trump or someone on his team bringing up the natural resources that fuel manufacturing and the president’s Made-in-the-USA dreams.

They’re an increasingly important fulcrum, or bargaining chip, in U.S. deals with the rest of the world.

“There is a strong trend toward a ‘minerals-for-security’ or ‘minerals-for-aid’ approach. A new U.S. trade deal with Indonesia, which is a global supplier of copper and other critical minerals, exemplifies this,” said Christopher J. Dolan, an assistant teaching professor of homeland security and public policy at Pennsylvania State University.

The intense focus on minerals and coveted elements is an acknowledgment that American industry risks falling behind in military technology, artificial intelligence and other high-tech ambitions unless it gains market share and starts digging and refining at home.

A U.S. Geological Survey report said imports made up over half of the U.S. consumption for 46 nonfuel mineral commodities in 2024. It was 100% reliant on imports for 15 of those minerals, such as gallium and manganese.

U.S. mining slowed in the final decades of the 20th century as labor and material costs grew alongside environmental restrictions, according to experts.

Companies looked abroad for minerals, and Mr. Trump is trying to strike deals that tap into foreign resources while spurring a mining boom at home through deregulation and permit reforms.

“They have tremendous copper, quality copper, and probably the most copper – and we made a deal with Indonesia,” Mr. Trump said Wednesday, extolling his latest trade deal to reporters huddled in the Oval Office.

The stakes are high and intertwined with global affairs.

Rare earths and precious elements are critical to 21st-century technologies – renewable energy technologies, electric vehicles, satellites, fiber optics and military uses such as precision-guided munitions and advanced radar.

Mr. Trump’s focus on minerals was apparent from the start of his term this year.

He talked about annexing Greenland, home to lithium and titanium that is used in smartphones, semiconductors and other technologies.

His push for Ukraine’s minerals, in exchange for America’s financial support against the Russian invasion, led to tense negotiations with Kyiv.

Mr. Trump and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy struck a deal that gives the U.S. dibs on minerals while helping Ukraine rebuild from the war’s devastation.

China produces most of the world’s supply of rare earth minerals used in electric vehicles, weapons systems and semiconductors. The seven rare earths are samarium, gadolinium, terbium, dysprosium, lutetium, scandium and yttrium.

Samarium, in particular, is used in heat-resistant magnets that are critical components of missiles and fighter jets.

The U.S. has rare earths but fell behind China when it seemed, in prior decades, that importing the minerals would be more cost-effective than extracting and processing them here.

China gobbled up a majority of the export market and, at times, withheld the resources as a diplomatic tool.

During a trade spat this year, the U.S. said China was slow-walking permits to export the minerals to American companies.

A deal negotiated in London resumed shipments. China, in return, got relief on tech-export controls and visas for its students attending U.S. colleges.

Even a Trump-facilitated peace deal between factions in the Democratic Republic of Congo and neighboring Rwanda had a minerals component.

The eastern Congo region is home to large reserves of valuable, rare minerals, including tungsten.

“I was able to get them together and sell it, and not only that, we’re getting for the United States a lot of the mineral rights from the Congo,” Mr. Trump said.

This approach has potential downsides.

“Linking humanitarian aid or peacekeeping efforts to mineral access might raise ethical concerns, especially if it looks to exploit conflict-affected nations for economic benefit,” Mr. Dolan said. “It may also increase competition with other major countries like China, resulting in a new competition in Africa or other resource-rich regions or result in a disregard for environmental, social, and governance and prolong unethical mining operations.”

Links between earthly treasures and geopolitical concerns are hardly new.

“It was true with oil for more than 40 years, until the shale revolution increased U.S. oil production enormously,” said Scott Montgomery, a geoscientist and lecturer at the University of Washington. “But for those decades, ‘foreign oil’ —meaning, above all, importing crude from OPEC countries — defined a major national security and foreign policy concern.”

Now the focus is on precious minerals. The White House is hoping to kickstart U.S. production while using quick executive actions and bilateral relationships to secure resources abroad.

The Biden administration was concerned about precious minerals, though it worked in a more deliberative fashion and collaborated with multiple countries, particularly to speed the green-energy transition.

“The Biden administration moved more slowly, was more process-driven, and was more collaborative and often behind-the-scenes. The Trump administration’s approach is quick, with little emphasis on process, and more focused on U.S. interests narrowly defined,” said Cullen Hendrix, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

He said demand for certain minerals may decrease because the GOP Congress withdrew funding for some green-energy projects in its One Big Beautiful Bill.”

Mr. Trump signed an executive order in March ordering agencies to speed the approval of minerals-production projects.

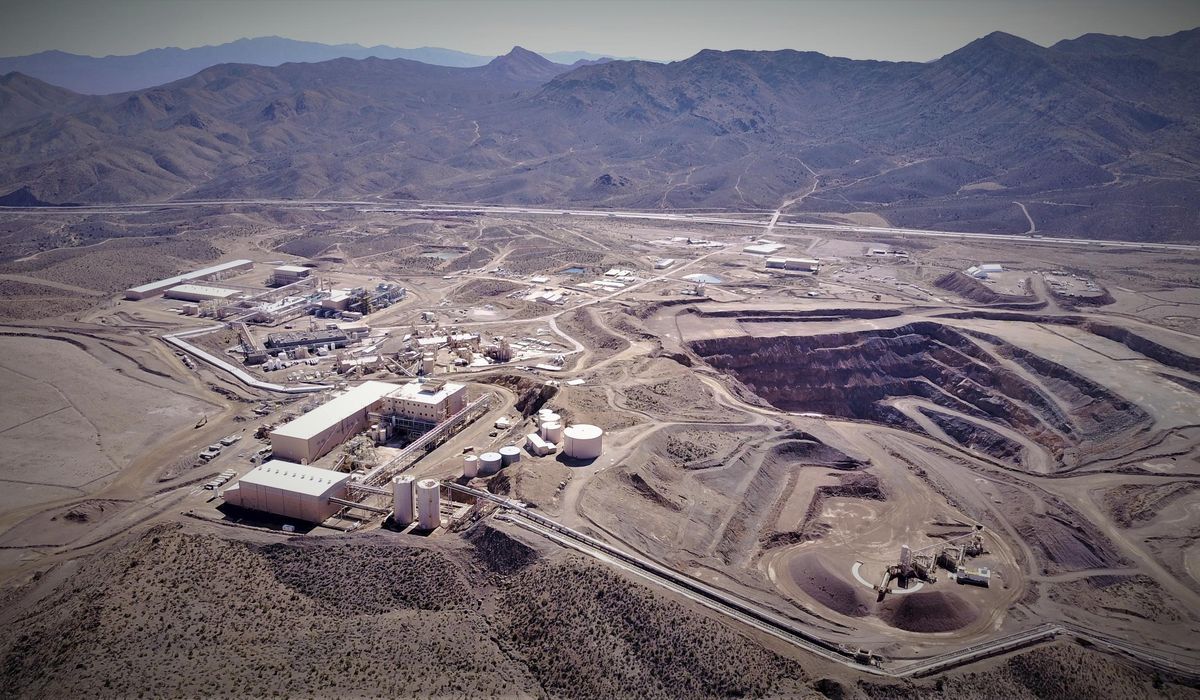

The U.S. is tapping into rare earth minerals in multiple promising projects, such as MP Materials’ Mountain Pass mining in California and Ramaco Resources’ Brook Mine operation in Wyoming.

“Developing [these minerals] at a high level again is already running into serious problems, with challenges from local people, including native groups, and from environmental rules,” Mr. Montgomery said. “This helps explain the Trump administration’s attempts to expedite permitting, reduce regulations, and pursue other avenues to foster development.”

The Essential Minerals Association, a trade group, said it supports policies that will “lessen America’s dependence on hostile nations,” but it recognizes that it doesn’t have deposits for every mineral necessary for its manufacturing. It would like the administration to collaborate with Canada and Mexico “to help support those demands.”

The association would like the administration to be “equally aggressive” in developing processing facilities alongside extraction, and wants consistency in U.S. policies.

“While we applaud the administration’s focus and investment in rapid domestic mineral development,” the EMA said, “it is imperative that Congress pass reforms that will provide the business community with certainty that they will not see dramatic shifts in our laws and regulations after every election.”

• Tom Howell Jr. can be reached at thowell@washingtontimes.com.