Hopes are fading fast to reduce tensions on the Korean peninsula, according to America’s former intelligence chief, who warned this week that the combination of increasingly provocative behavior from Pyongyang with the near-total loss of diplomatic leverage on the U.S. side has resulted in a uniquely dangerous moment in the region.

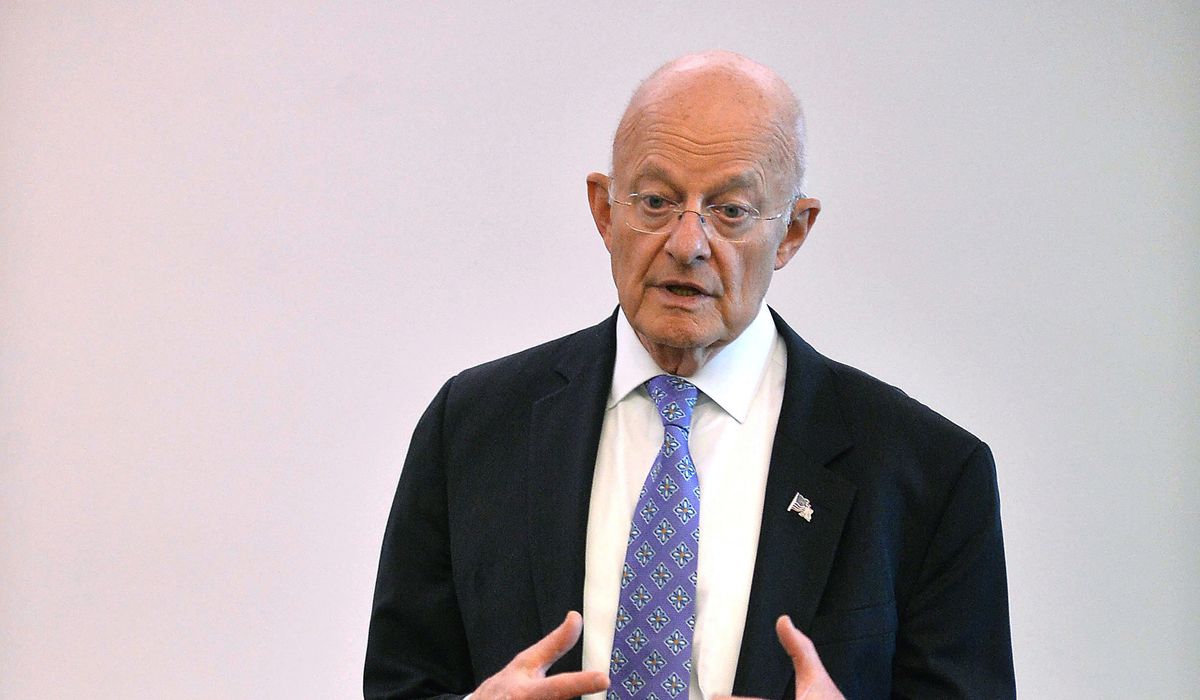

Speaking at Tuesday’s “The Washington Brief,” a monthly forum hosted by The Washington Times Foundation, former Director of National Intelligence James Clapper said there are few obvious options available to Washington and its allies in the face of numerous rounds of North Korean missile tests, an apparent effort by Pyongyang to expand its nuclear capabilities, and hostile rhetoric aimed at South Korea.

Mr. Clapper said that the Biden administration appears to have little in the way of ambitious new policies to put forward on North Korea. But he stressed that even if the White House decided to launch a major push to engage with Pyongyang, it’s not clear what that might look like, given that the historic, personalized olive-branch diplomacy used by former President Donald Trump ultimately failed to secure any kind of lasting denuclearization deal with North Korea.

“At this point, I don’t see much prospect for reducing tensions, unfortunately,” Mr. Clapper said at the Washington Brief event, which was moderated by former CIA official Joseph DeTrani.

“It doesn’t appear that the administration is really interested in pursuing some sort of initiative. And even if they were, I think we’ve lost a lot of the leverage we once had to induce real change in the North’s behavior. … They’ve given up on diplomacy, at least with us.”

“I think at one point they were interested in diplomacy and were interested in negotiation and were interested in recognition,” Mr. Clapper said. “I don’t think so now.”

The Biden administration has said repeatedly it is prepared for new direct talks with the North with no preconditions, but the North has effectively refused to answer and direct contacts between Washington and Pyongyang have effectively ceased.

The grim picture painted by Mr. Clapper comes against a series of fast-moving events on the tense, divided Korean peninsula that feed the growing consensus in national security and intelligence circles that the region is entering an especially dangerous period. Just last week, for example, North Korea test-fired yet another barrage of cruise missiles off its west coast, its fourth such test just since the start of the year.

Analysts say that under North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, Pyongyang’s military is seeking to diversify its platforms of weapons of mass destruction beyond its ground-based missile units. In South Korea, there’s another reason for concern: President Yoon Suk Yeol warned last week that he believes Pyongyang could launch new provocations ahead of April’s parliamentary elections in Seoul.

On the symbolic front, there are other signs that the dynamic has shifted for the worse. In Pyongyang, the North Koreans appear to have torn down a monument that symbolized reconciliation with South Korea. Days before that monument came down, Mr. Kim formally declared South Korea a hostile foreign adversary.

At the same time, Mr. Kim has deepened his strategic alliance with Russia. North Korea has provided Moscow with arms and ammunition for its war in Ukraine.

Dropping the ball?

Provocative actions are hardly surprising when it comes to North Korea. But specialists say it’s the sheer number of such actions, combined with the absence of any sign of movement on U.S.-led diplomacy, that provide cause for rising alarm.

“If you add to that the acceleration of [weapons of mass destruction] programs … with all the latest ICBM tests, the tests of cruise missiles, surface-based, submarine-based, what have you, clearly the impression one gets is that something unusual which we haven’t seen before might be unfolding before our eyes,” said Alexandre Mansourov, professor at Georgetown University’s Center for Security Studies, who also spoke at The Washington Brief forum.

“And then, of course, here’s my question: Has the Biden administration really dropped the ball?” he asked.

Mr. Clapper said in response that the U.S. is essentially “stuck,” with the administration unable to take any kind of diplomatic tack that could be seen as giving concessions to Pyongyang. Any such effort, he said, would run into a “buzzsaw” of domestic American politics.

“At this point, I think any great new idea that any of us may have about how to approach the North Koreans is kind of a dead letter,” Mr. Clapper said.

During the Trump administration, the U.S. seemingly gave Mr. Kim every opportunity to strike a deal that would lighten sanctions and open up economic investment in North Korea in exchange for a verifiable end to the country’s nuclear weapons program. Mr. Trump even held three precedent-shattering face-to-face meetings with Mr. Kim in the hopes of securing a deal, but ultimately, no agreement was reached.

While denuclearization of the peninsula remains the ostensible U.S. goal, there are worrying signs on that front, too. Mr. DeTrani cited recent polls showing that a strong majority of South Koreans — more than 70% in multiple surveys — support their nation acquiring its own nuclear weapons, or pushing Washington to bring back the tactical nuclear weapons it had stationed in South Korea until the early 1990s.

Mr. Clapper argued that America’s best course of action now might be to change course from its insistence on “denuclearization” as the end goal and instead recognize that North Korea is, in fact, a nuclear-capable state.

“I become an advocate for recognizing reality and acknowledging, officially, they have nuclear capabilities,” he said. “Doing so doesn’t raise or lower the intrinsic threat that they pose one bit, and plays to their need for ‘face,’ for respect, and maybe puts them in a better mood to negotiate.”

• Staff writer Andrew Salmon contributed from Seoul, South Korea, to this story, which is based in part on wire service reports.

• Ben Wolfgang can be reached at bwolfgang@washingtontimes.com.