Part 2 of 3

Congressional intern Brentin Ungar never expected to be supplementing his income by hustling for tips at a pizza bar after graduating from Wabash College with a liberal arts degree last year.

“Things have been going slow since graduation,” said Mr. Ungar, who earns $2,600-$3,000 a month from his Capitol Hill and pizza parlor jobs and spends most of his tips on public transportation and food.

The 23-year-old Ohio native, who earned a bachelor of arts degree in history and political science from the tiny all-male institution in Indiana, also is studying for the foreign service. Nearly a year after college, he bunks with relatives in Northern Virginia and has no intention of attending graduate school as he pays off $20,000 in federal student loan debt.

Mr. Ungar’s situation is emblematic of many alumni of the nation’s humanities programs, as soaring costs prompt families to question the value of a four-year undergraduate degree. Education experts say the liberal arts produce the majority of employment-challenged graduates.

Kenyon College, a small liberal arts school in Ohio, now charges the highest tuition of any private institution in the nation — nearly $67,000 a year for undergraduates. But last year’s liberal arts graduates earned an average salary of just $39,349 a year in fields such as writing, social work and hospitality, according to Zippia.

“A lot of people are finding out it’s not worth it,” said former Education Secretary William Bennett, an academic philosopher and onetime associate dean of liberal arts at Boston University.

With liberal arts students paying premium tuition but earning half the income of their classmates in science and engineering, universities have started closing humanities departments and trimming traditional subjects — even English and mathematics — to offer only specialized classes needed for more lucrative majors.

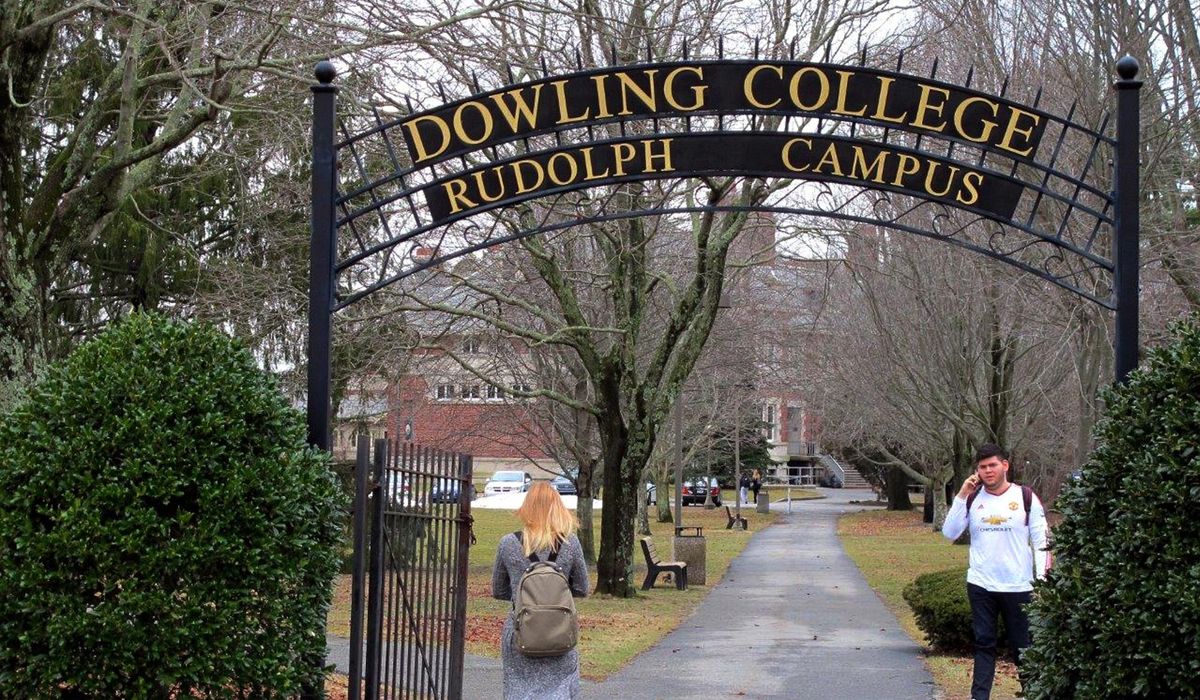

And dozens of small liberal arts colleges have folded or downsized since the COVID-19 pandemic shuttered campuses in March 2020. In Minnesota last month, board members at the all-female College of Saint Benedict and all-male Saint John’s University approved eliminating several liberal arts programs, citing declining interest. Located near each other, the linked Catholic schools have a combined undergraduate enrollment of 2,900 students and share the same facilities and staff.

Citing inflationary pressures and slumping enrollment, Cazenovia College in central New York will close at the end of the school year, making it among the latest to bite the dust.

“For the most part, all of liberal education is on the skids, and much of it deserves its fate,” said John Agresto, a former acting chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities under President Reagan. “Unless there’s a reformation in how we see, explain and understand the liberal arts, it’s not worth saving.”

Liberal arts advocates have long argued that they serve as a “finishing school” for careers in business, law and medicine that often require additional graduate degrees. A liberal arts education not only nourishes the soul, but also develops the habits of thinking deeply, writing coherently, speaking clearly, listening carefully and making sound judgments — qualities valued by employers, they say.

The value of “knowledge for its own sake,” as ancient Greeks understood a classical education, lies in having surgeons who know ethics, defense attorneys who have mastered public speaking and politicians well-versed in history and political science.

‘College is Worth It’

The National Association of System Heads, which represents the leaders of 65 university systems, in December announced a “College is Worth It” campaign to fight what it calls a growing “crisis of confidence” in the value of higher education.

Part of the campaign examines how four-year undergraduate degrees drive social mobility and individual prosperity — areas in which liberal arts programs, even those preparing students for careers in law and medicine, have struggled to offset rising tuition costs.

Making matters worse, employers who previously required a four-year college degree have stopped insisting on it as they struggle to address pandemic-era labor shortages.

In Pennsylvania, 92% of state government jobs will no longer require a college degree, under a recent executive order from Democratic Gov. Josh Shapiro.

“Many middle-class and upper-middle-class white-collar jobs are dropping college degree requirements, including paralegals, real estate agents and human resources assistants,” said Preston Cooper, senior fellow at the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity, a free-market think tank in Austin, Texas. “Students should research the occupations they are interested in and determine whether a four-year college degree will help them succeed.”

Electricians, plumbers, welders, roofers, masons, carpenters and cosmetologists with high school diplomas already make more money than liberal arts graduates, noted electrical contractor Joshua Page, an author and TED Talks speaker who skipped college. He said electricians starting out in Massachusetts earn $26-$55 an hour.

“They require a willingness to work, to work hard, work with your hands and your brain,” Mr. Page, 38, said in an email.

A “C” and “D” student in school, Mr. Page said he went to work for an electrical contractor four days after graduating from Montachusett Regional Vocational Technical High School in Fitchburg, Massachusetts. Now he owns three electrical companies.

“I think we will see an increase in people wanting to work in the trades and seeking other alternatives than just college,” he said. “The cost of college is so great and the cost of living is even greater. One thing about the trades is no robot can ever replace what we do.”

Falling enrollment

According to the Department of Education, total undergraduate enrollment fell by 9% from 17.5 million students in 2009 to 15.9 million in 2020. But the education department projects enrollment will grow again by 8% from 15.9 million in 2020 to 17.1 million students in 2030, driven largely by surges in international and first-generation student applications.

Meanwhile, most liberal arts programs at public and private colleges have stopped offering the Western civilization-based core curriculum that once defined their studies. They now focus instead on pursuing lucrative federal grants and private donations for research into trendy studies related to race, sexuality, ecology and gender.

“Why do I want to save a program that’s teaching a woke curriculum instead of the classic core curriculum covering the whole scope of human learning? It’s not what it used to be,” said Mr. Agresto, the former NEH member.

From 1989 to 2000, Mr. Agresto served as president of St. John’s College in Santa Fe, New Mexico, a private liberal arts school with its main campus in Annapolis, Maryland. In 1937, St. John’s became a Great Books program, reorganizing its teaching around seminar discussions of primary sources, making it an outlier in higher education trends.

“Go to almost any school’s catalog and look at the titles of the courses in English, history and classics, and they all revolve around things like ‘women in antiquity’ or ‘homosexual responses to classical learning,’” said Mr. Agresto, who holds a doctorate in government from Cornell University. “That’s what young professors today learn in their graduate schools and what they want to teach. Why not study Western civilization? Because it’s racist, sexist and homophobic, and the documents are all written by people who owned slaves.”

The decline of the liberal arts further snowballed as thousands of young people skipped college during the pandemic, creating an enrollment crisis as they headed straight into the workforce.

Overall undergraduate college enrollment dropped 8% nationally from 2019 to 2022 and did not rebound even after colleges resumed in-person classes, according to the National Student Clearinghouse. The drop in the rate of high school graduates going to college since 2018 is the steepest on record, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The number of freshmen enrolling in college increased slightly from 2021 to 2022, but remains well under pre-pandemic levels. By contrast, demand has soared for apprenticeships in the trades, with the Department of Labor reporting that the number of new apprentices has rebounded to near pre-pandemic levels after dipping in 2020.

To fill their dorms, colleges have increasingly offered scholarships to international and first-generation students. But while these scholarships once let students choose liberal arts majors, they are now restricted to recruit underrepresented minorities into lucrative technology majors such as computer science.

According to the Common Application, an undergraduate admissions program that 841 colleges and universities use, surging applications from first-generation and international students have offset a general trend of declining enrollment at four-year institutions since 2019.

And insiders say most of those kids are more interested in finding stable jobs than in discussing the classics from either a traditional or woke perspective.

From August to last month, the Common Application found underrepresented minority applicants increased by 31% over the same period in 2019-20, while first-generation applicants increased by 36%, nearly three times the rate of continuing-generation applicants.

The number of distinct applicants from outside the country increased at nearly triple the rate of U.S.-based applicants during that time, the company noted. China, India, Nigeria, Ghana and Canada were the leading countries for international applicants.

“For first-generation college students, many of them see it as a ticket to middle-class or better success, and they want fields with a clear path to success after college. Degrees in softer woke-ified areas are not likely to do that,” said anthropologist Peter Wood, president of the conservative National Association of Scholars.

A former associate provost at Boston University, he sees the trend as a brain drain that may help Chinese research universities surpass American institutions — at which point he predicts the pipeline will dry up.

“The magnet of American higher education that draws international students is our reputation for excellence in prosperous science, technology, engineering and math fields,” Mr. Wood said. “I’ve encountered very few international students coming here to seek liberal arts degrees, although some who find engineering and science too difficult settle for less demanding studies.”

⦁ Tomorrow: Preserving the liberal arts

The value of “knowledge for its own sake,” as ancient Greeks understood a classical education, lies in having surgeons who know ethics, defense attorneys who have mastered public speaking and politicians well-versed in history and political science.

A liberal arts education not only nourishes the soul, but also develops the habits of thinking deeply, writing coherently, speaking clearly, listening carefully and making sound judgments — qualities valued by employers, advocates say.

Yet college humanities programs have been struggling for years to attract students, with COVID-19 shutdowns exacerbating higher education’s problems. Colleges and universities nationwide now are slashing their humanities programs, with some liberal arts schools shutting down entirely.

This three-part series examines the role that the push for STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) education has played in the decline in interest in the humanities; the growing challenges that liberal arts programs face, from sky-high tuition to dropping enrollment; and the effort by conservatives and Christians to save traditional humanities education.

• Part 1: Colleges’ focus on STEM is killing liberal arts programs

• Part 2: Liberal arts programs face mounting challenges

• Part 3: Conservatives, Christians work to preserve traditional liberal arts

• Sean Salai can be reached at ssalai@washingtontimes.com.