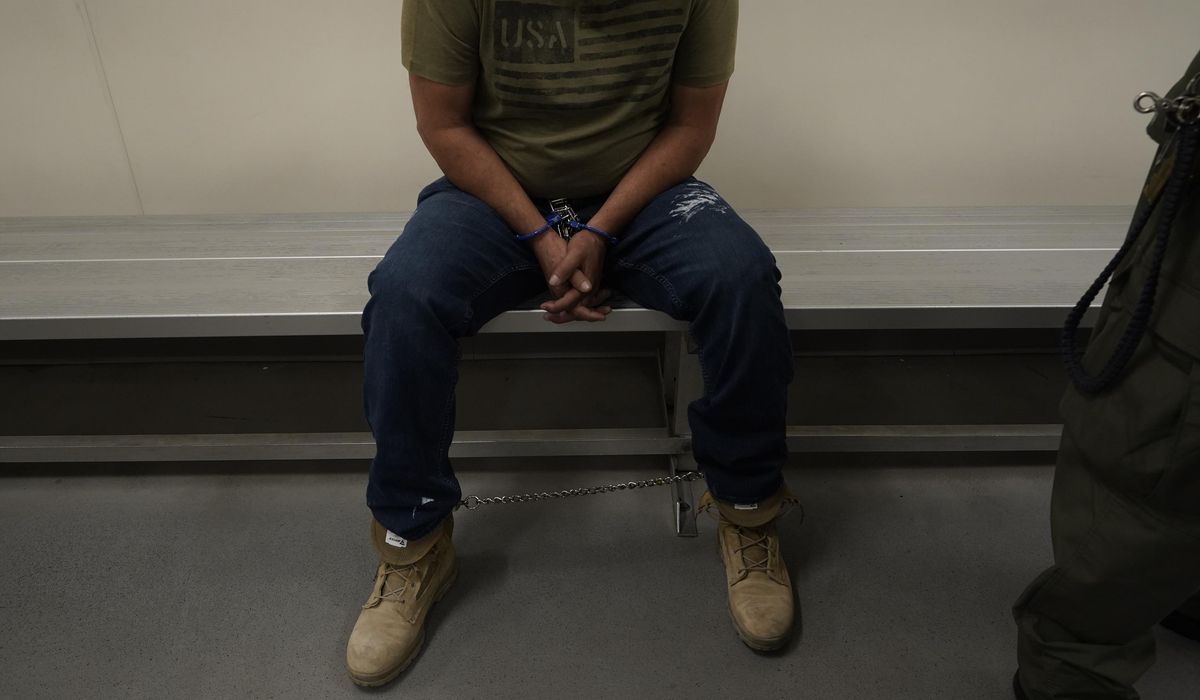

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement rekindled its policy that limits the illegal immigrants whom officers are allowed to arrest and deport, moving after the Supreme Court shot down a legal challenge to the policy.

The new rules, which lay out President Biden’s priorities for immigration law enforcement, say that being in the country illegally is no longer a sufficient reason for arrest or deportation.

The rules require agents and officers to justify each arrest and deportation target as either a threat to national security, a risk to public safety or a recent border crosser.

Officers also are directed to search for mitigating circumstances, or reasons not to deport someone, such as having family ties to the U.S., being advanced in age or having a criminal record years ago.

The policy, which Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas created in 2021, had been on hold while a challenge worked its way through the federal courts, but The Washington Times has learned it’s back in effect.

“ICE personnel will reinstitute the [priorities] as outlined in the September 2021 memorandum, ensuring that aggravating and mitigating factors for enforcement actions are fully considered and assessed,” Corey A. Price, acting executive associate director of ICE’s Enforcement and Removal Operations, told employees in a new memo, citing the Supreme Court’s June ruling.

SEE ALSO: DHS cancels deportation request for hit-and-run killer

Rank-and-file ICE officers chafed under the rules when they were implemented, saying it was difficult to make even basic arrests. And the bureaucratic hurdles officers had to go through to get approval sometimes meant that even if they got the OK it could take hours and their target may have eluded them.

“It’s put so much friction in the system that we go weeks without arresting somebody,” one officer told The Times. “It seems like a coordinated effort to come up with excuse after excuse for us not to do our job.”

In response to questions, ICE didn’t detail how the revived memo will change its operations. Instead, it provided a copy of another memo from acting Director Patrick J. Lechleitner, who said staff will go through a refresher course to make sure officers are making “consistent, fair and efficient” use of the priorities.

The Supreme Court, in an 8-1 ruling in June, rejected a challenge by Texas and other GOP-led states. The court’s majority concluded that states didn’t have legal standing to challenge the policy, though it did not rule on the legality of the policy itself.

During litigation in lower courts, Texas proved that under the memo ICE was refusing to arrest and deport illegal immigrants who were in fact serious criminals.

Indeed, ICE canceled detainer requests — a part of the deportation process that asks local authorities to turn over criminals when they have completed their state sentences — for some of those criminals.

Among them was Heriberto Fuerte-Padilla, an illegal immigrant from Mexico who was driving drunk in 2020 when he smashed into a Mazda driven by a Texas teenager, killing her. He tried to run away from the scene, but an off-duty police officer chased him down.

It’s not clear why Mr. Fuerte-Padilla didn’t meet Mr. Mayorkas’ priorities, though ICE officers told The Times that the secretary’s memo was so vague and supervisors so worried about running afoul of leaders that they were erring deeply on the side of releasing criminals.

“It’s a moving target and the bar is always increasing,” one West Coast officer said.

ICE, citing Mr. Mayorkas’ policy, also canceled detainer requests for immigrants with convictions of drunken driving, evading arrest and domestic violence.

Mr. Mayorkas defended his memo as a way to make better use of limited enforcement resources.

He said he wanted officers and agents to focus on priority cases and leave rank-and-file illegal immigrants alone.

“The fact an individual is a removable noncitizen therefore should not alone be the basis of an enforcement action against them,” he wrote. “We will use our discretion and focus our enforcement resources in a more targeted way. Justice and our country’s well-being require it.”

He said ICE should focus on aggravated felons rather than other illegal immigrants.

The result was a lack of enforcement across the board.

In 2019, ICE removed 150,141 convicted criminals. In 2020, the last full year under President Donald Trump, even with the pandemic limiting operations ICE removed 103,762 convicted criminals.

In 2021, with Mr. Biden in office, ICE removed just 39,149 convicted criminals. In 2022, even as the pandemic waned, the total dropped to 38,447 — less than half the agency’s target.

ICE officers said they were under pressure not to bring cases to their supervisors unless they were likely to be approved, for fear of being seen bucking the new rules.

The West Coast officer said they were even discouraged from deporting illegal immigrants who had a final deportation order and who were linked to gangs.

“We’re submitting police reports and all kinds of documents and nothing seems to be good enough,” the officer said. “Nobody qualifies for arrest.”

Mr. Mayorkas’ memo was the most stark limit on enforcement, but it’s not the only one.

The surge of illegal immigrants at the border has proved a distraction, siphoning manpower and resources away from ICE’s mission of removing illegal immigrants from the interior.

ICE has also found itself with a detention bed space crunch, which some officers say places an even bigger limit on their ability to arrest and deport illegal immigrants than Mr. Mayorkas’ memo does.

• Stephen Dinan can be reached at sdinan@washingtontimes.com.