SEOUL, South Korea — In most countries, it would be extraordinary for a former president to strip to his underwear and lie prone on the floor of his detention cell to resist being removed for interrogation, but in South Korea, such treatment is — almost — a norm.

It would be unthinkable in North Korea, where leaders abandon power only after death, and then they are memorialized with mausoleums, portraits and statuary.

In South Korea, the opposite is true. Ex-presidents suffer high-profile, intrusive investigations into themselves and their families that always result in negative outcomes — from jail terms to suicide.

North Korea’s system is hardly unique among dictatorships, but South Korea’s may be unique among democracies.

Whether Seoul’s practice represents an extreme of political vengeance or a system of utmost accountability is debated.

However, experts caution alarmed overseas observers not to misinterpret ritualistic political theater as murderous justice.

All weapons aimed at Yoon

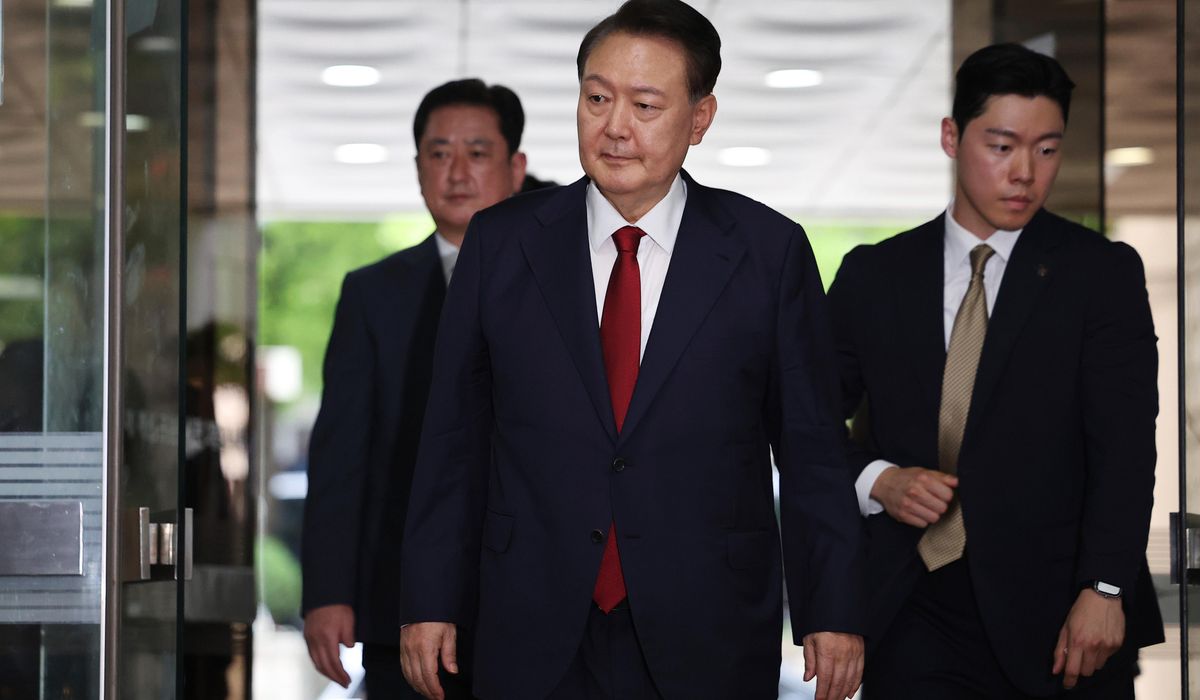

Impeached ex-President Yoon Suk Yeol is in detention facing multiple charges, including insurrection over his failed declaration of martial law in December.

He lay on the floor of his detention cell in his undershirt and underpants last week to avoid being removed for questioning by prosecutors, who eventually gave up, fearing the 64-year-old might be physically injured. They have been granted a fresh warrant. Mr. Yoon, a former head prosecutor before becoming president, knows to be wary of prosecution interrogation.

South Korean investigators no longer deploy electric shocks or waterboarding, as they did during authoritarian rule, which ended in 1987. However, the judicial system favors prosecutors over defendants.

“Confessions, often reached through marathon 10-plus-hour interrogation sessions at the Prosecutor’s Office, are the main piece of evidence employed in reaching a guilty verdict,” noted Hwang Ju-myung, a former Constitutional Court research judge, in a 2017 article. These practices resulted in a conviction rate of 99.3% between 2013-2017, he found.

With police, military police, prosecutors and special investigators casting a wide net, it is not only Mr. Yoon who faces judgment. Former members of his administration, as well as wife, aides and military officers are being investigated.

His wife, Kim Keon-hee, who stands accused of charges including stock price manipulation and corruption, has been questioned. On Thursday, a warrant was issued for her pretrial detention. A Seoul court is set to rule on the warrant next week.

Churches also have been impacted. The Yoido Full Gospel Church and the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification have been raided by investigators seeking evidence of collusion with figures in, or close to, the former administration.

A senior figure in the Family Federation was questioned by prosecutors Friday over alleged bribery of Ms. Kim.

The Family Federation, formerly the Unification Church, is the owner of The Washington Times.

Overseas visitors were stunned by the scale of the investigators’ raid on the Family Federation.

However, deployment of massed law-enforcement personnel is typical in Korea, be it to oversee demonstrations or support prosecutors. So is deployment of massed legal force against former presidents.

Justice, vengeance or ritual?

South Korea was established as a state in 1948. Since then, just one of its former presidents has escaped legal tribulations.

President Rhee Syngman was exiled. President Park Chung-hee was assassinated by an aide. Ex-Presidents Chun Do-hwan and Roh Tae-woo were respectively sentenced to death and life imprisonment. (Both sentences were later commuted.)

Ex-Presidents Kim Young-sam and Kim Dae-jung both saw family members jailed. Ex-President Roh Moo-hyun committed suicide amid probes into his family. Ex-President Lee Myung-bak was jailed, as was impeached ex-President Park Geun-hye — whose house and assets were also seized by authorities.

Only Mr. Yoon’s predecessor, President Moon Jae-in, escaped unscathed.

Some observers praise such accountability.

“In North Korea, the leader has absolute power, he is almighty, he is above the constitution and the laws,” said a North Korean defector who spoke anonymously, as his employer had not given him permission to speak to media. “But here in the free democratic world, the president is elected for a certain term to serve the country and after that, he becomes a normal citizen who should abide by laws. That is the difference.”

Others are deeply concerned. Mr. Yoon, if found guilty of insurrection, could face the ultimate penalty.

“Save freedom! Protect President Yoon!” American conservative Gordon Chang posted on social media. Responses to his tweet expressed fear about Mr. Yoon’s death and even called for divine assistance.

While Mr. Yoon’s fate is uncertain, execution looks highly unlikely. Capital punishment remains on the legal books, but there has been a full moratorium since 1998.

One Korea pundit cautioned that the current political-judicial spectacle is a domestically well-understood and oft-practiced ritual, that is less dire than it may appear to outsiders.

If found guilty, “The prosecution will probably ask for a death penalty but will not get it and Yoon will be out of jail in five years,” said Mike Breen, Seoul-based author of “The New Koreans.” “It’s political theater.”

Though some received sentences of longer than three decades, not one of Korea’s jailed ex-presidents served a full term. All were granted pardons after public emotions had cooled.

“The system does not take itself seriously,” Mr. Breen said. “It is pure theater — but nobody calls it out.”

Despite this in-built mercy mechanism, Mr. Breen, who has been in the country since the 1980s, excoriated the optics of the trend.

“You don’t force everyone to do the perp walks, it is unnecessary and designed to make people look guilty so the prosecutors can strengthen their cases,” he said.

That is a reference to in-court parades of the accused in prison garb and the related media fascination with the undignified appearances of those who were formerly high and mighty.

That fascination was on display during the attempted rendition of Mr. Yoon and was criticized by his legal team.

Mr. Breen also warned that the cycle likely would repeat itself after President Lee Jae-myung exits office and the political pendulum swings.

While Mr. Lee enjoys presidential immunity during his five-year term, he remains accused of charges ranging from lying during an election to illegally sending funds to North Korea.

• Andrew Salmon can be reached at asalmon@washingtontimes.com.