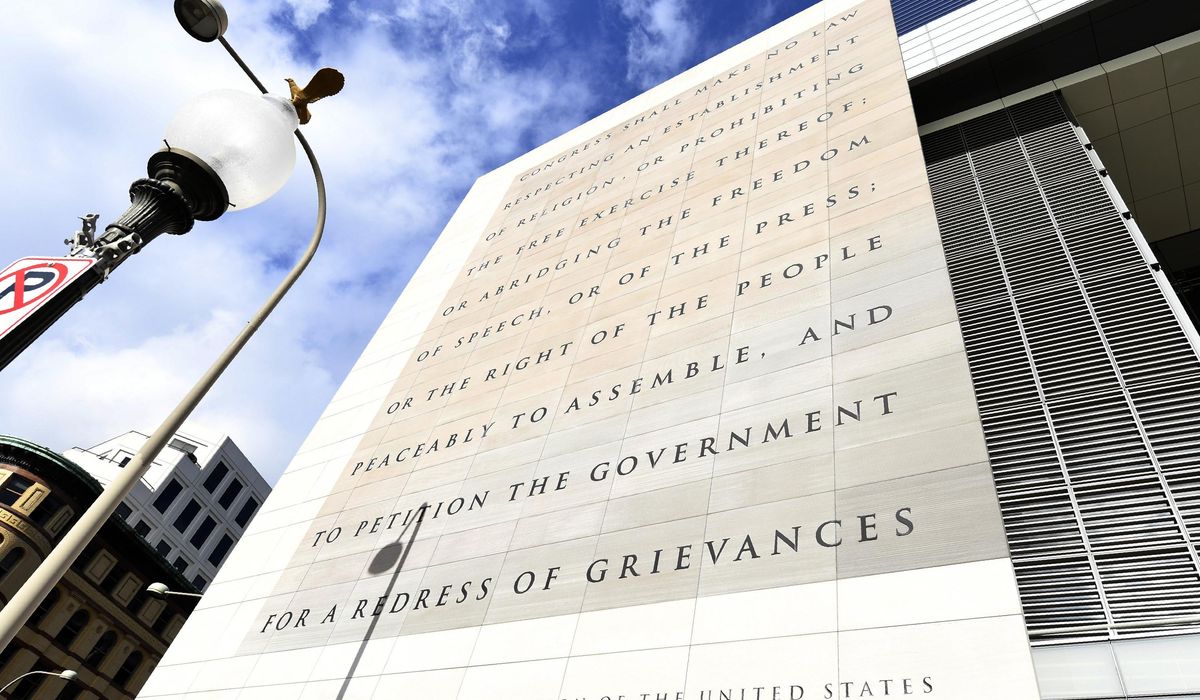

Just in time for Constitution Day, an annual survey finds that most Americans know little about their constitutional rights ahead of November’s elections.

In an online survey of 1,590 adults, the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg Public Policy Center found that just 39% knew that the First Amendment protects freedom of religion and only 29% recognized that it guarantees freedom of the press.

The findings build on decades of public surveys showing downward trends in civics knowledge and trust in U.S. institutions.

Several political scientists, legal scholars and historians interviewed by The Washington Times warned that growing apathy could destabilize the nation as voters head to the polls this fall.

“If people don’t appreciate their rights or the Constitution and institutions that protect them, the conditions seem ripe for democratic failure,” said Paul Brace, a political scientist at Rice University.

Annenberg found that adults who completed the fill-in-the-blanks survey in May similarly struggled to name the other three freedoms guaranteed in the First Amendment.

“As you may know, the First Amendment is part of the U.S. Constitution,” one question stated. “Can you name any of the specific rights that are guaranteed by the First Amendment of the Constitution, or not?”

While 74% could name freedom of speech, 27% identified the right to assemble and 11% knew about their right to petition the government.

On a current events topic with only two possible answers, just over half of adults knew that Democrats control the Senate (55%) and Republicans control the House of Representatives (56%).

“Civics knowledge matters,” said Kathleen Hall Jamieson, director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania and the survey. “Those who do not understand the rights protected by the Constitution can neither cherish nor invoke them; those who do not know which party controls the House and Senate may misattribute credit or blame for action or inaction.”

The survey also found that 65% of adults could list all three branches — the legislative, judicial and executive — of the government.

Even more of those surveyed endorsed several of President Biden’s proposed changes to the Supreme Court. Roughly 8 in 10 said they support enforcing a formal ethics code and forbidding justices from participating in cases in which they have “personal or financial interests.”

Josh Blackman, a constitutional law professor at South Texas College of Law in Houston, expressed concern over this gap between knowledge of the federal government and desires to let the executive branch remake the judiciary.

“It is very sad that so many Americans know so little about their government,” Mr. Blackman said. “Moreover, when people opine on particular issues, such as reform of the Court, they largely lack the knowledge to assess the pros and cons of such proposals.”

Traditionally, adults who took a high school civics class have done better on the Annenberg survey since it launched in 2014. Historians say that’s significant.

“History and civics need more time in the curriculum,” James Grossman, executive director of the American Historical Association, said of the findings. “History and civics teachers need professional development that will enable them to stay current in their fields.”

Some said the results highlight a crisis in U.S. high school and college civics education.

“I don’t think we should take the findings with a grain of salt,” said Bequita Pegram, a social justice historian at Prairie View A&M University, a historically Black institution in Texas. “This should be alarming and eye-opening.”

Elesha Coffman, a cultural historian at Baylor University, said the results show many voters “lack the basic knowledge required to understand major national news stories or gauge whether statements they encounter on social media are grounded in reality.”

“There’s talk today of a government shutdown, for example,” Ms. Coffman said. “You can have partisan finger-pointing without knowledge of what a government shutdown entails, but any reasoned, worthwhile opinion on the matter requires a grasp of the branches of government.”

Others downplayed the Annenberg report and questioned the value of its hyper-specific questions.

“Why does it matter if most people can’t name chapter and verse and list all the rights in the omnibus and arbitrarily numbered First Amendment?” said Richard Gamble, an American historian at Hillsdale College, a private Christian school in Michigan.

Recent reports suggest political ignorance has expanded beyond the general public.

In July, the American Council of Trustees and Alumni reported that 60% of college students it surveyed failed to identify the term lengths of members of Congress — two years for the House, six for the Senate — on a multiple-choice test. Only 37% could correctly identify John Roberts as the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.

Bradley Jackson, ACTA’s vice president of policy, said the Constitution Day survey adds “yet another data point” showing alarming declines in public awareness of civil liberties, civic institutions and U.S. history.

“These results reveal that many voters lack a thorough understanding of American government and are likely voting without reference to its future strength and viability,” Mr. Jackson said. “The people cannot preserve a constitutional order that they scarcely understand.”

Donald Critchlow, director of Arizona State University’s Center for American Institutions, said it’s impossible to ignore the fallout of this ignorance.

In January, his center released a yearlong study of 150 college introductory U.S. history courses that found “identity-focused terms” such as “White supremacy” dominated their syllabi. By comparison, America’s founding, the Civil War, World War II, and the role of religion in civil rights movements all received scant attention.

“We know that hate crimes against religious groups, Protestants, Catholics, and Jews have increased,” said Mr. Critchlow, a U.S. history professor. “If rights are not known by American citizens, they have no meaning. And rights are the foundation of our unique experiment in democracy.”

Observed on Sept. 17, Constitution Day commemorates the 1787 signing of the nation’s government charter and those who have become U.S. citizens.

• Sean Salai can be reached at ssalai@washingtontimes.com.