The late political philosopher Frank Meyer engaged in secret liaisons and experienced persecution from communists on his way to founding modern American conservatism, according to a biography based on thousands of newly discovered documents.

Author Dan Flynn says Meyer’s concept of fusionism, a hybrid of libertarian economics and traditional social values, grew to reshape Republican politics in the late 20th century.

“The idea of fusionism originally came to him as a communist,” said Mr. Flynn, a senior editor at the conservative American Spectator. “He wanted to link communism to more patriotic themes and the American founding.”

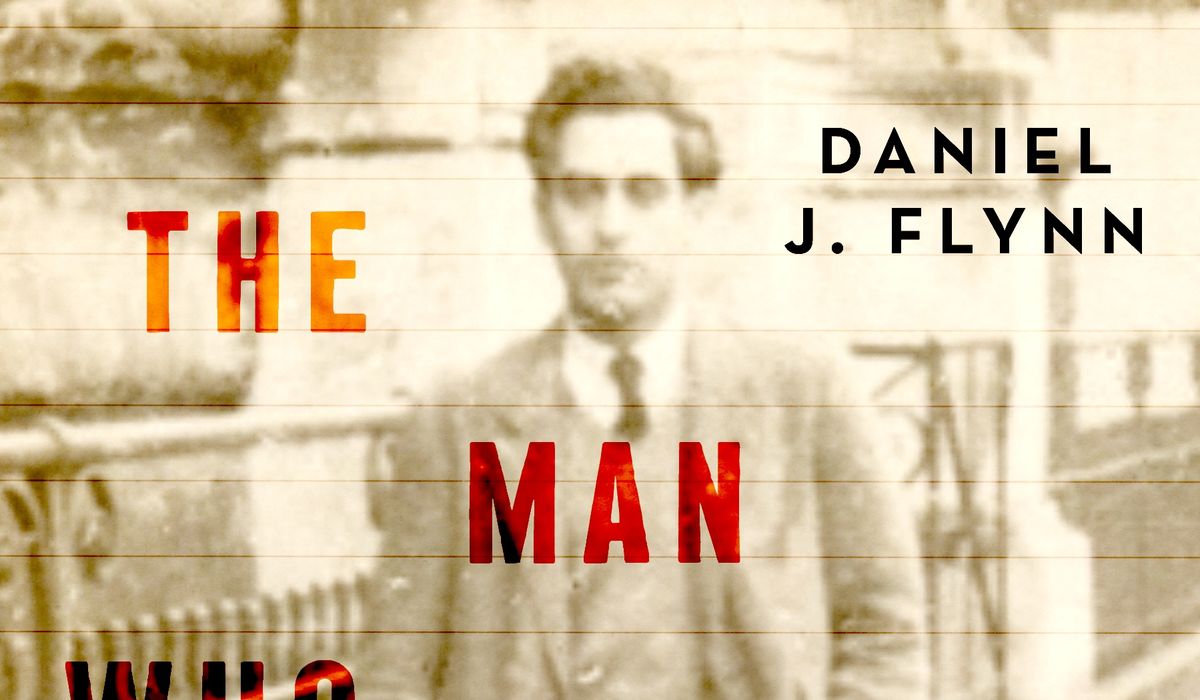

Published Tuesday, Mr. Flynn’s book “The Man Who Invented Conservatism” offers fresh revelations about Meyer, who was born to an affluent New Jersey Jewish family in 1909.

Meyer transitioned from youthful communist activist to spending the last years of his life, 1955 to 1972, as a founding editor of the conservative National Review magazine.

In August 2022, Mr. Flynn discovered roughly 250,000 of Meyer’s unpublished personal papers in an Altoona, Pennsylvania, warehouse. He spent the next 19 months transcribing them.

He also obtained declassified British intelligence detailing a communist campaign to erase Meyer from the party’s history books.

Those documents revealed that Meyer, who founded a communist student club while studying at Oxford University and sat on the board of the Communist Party of Great Britain in the 1930s, secretly dated the daughter of British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald.

Sheila MacDonald, a fellow Oxford student, tried to sway him toward her family’s Social Democratic views as he courted her.

“What should be aimed at is not so much ‘rights for everyone’ as a friendliness amongst everyone, and Communism is the unlikely method to bring that about,” Miss MacDonald wrote to him in a May 1933 letter cited in the book. “That is why I dislike class-war — it only accentuates the disease of hatred.”

In another letter, MacDonald invited Meyer to dinner at 10 Downing Street, the prime minister’s official residence, while her father was away.

Meyer earned his B.A. from Oxford in 1932 and his M.A. in 1934. He went on to study at the London School of Economics and became president of its student union.

There, his communist activism led him to be expelled and promptly deported from England in 1934.

Evolving beliefs

Back home, Meyer remained active in communist politics, recruiting Americans to fight on the Soviet side of the Spanish Civil War from 1936 to 1939.

He later received permission to enlist in the U.S. Army during World War II, but an injury during basic training kept him from seeing combat.

According to Mr. Flynn, guilt over sending men to their deaths in Spain and a close reading of the free-market Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek led Meyer to reassess his beliefs.

Meyer worked with Earl Browder, then the general secretary of the Communist Party of the United States, to foster cooperation between American and Soviet communists.

As the Soviet Union became a U.S. enemy with the war’s end in 1945, U.S. communists forced Browder out of leadership and Meyer left the party to become a Truman Democrat.

“Joining the Army in 1942 placed him alongside plumbers, laborers and other regular guys who weren’t ready to overthrow the American government,” Mr. Flynn said in an interview with The Washington Times. “Because he lived in a bubble of social isolation, wealth and privilege, he hadn’t realized these guys were essentially happy with their lives.”

Mr. Flynn noted that communists pressured Meyer’s wife, Elsie, to divorce him as “ideologically unsound,” but she refused.

Continuing his transformation, Meyer was one of five former communists who testified in the 1949 Smith Act trial in New York, helping send 11 party leaders to prison for conspiring to overthrow the U.S.

Mr. Flynn’s stash of documents revealed that Meyer’s former communist colleagues in Great Britain heard about the trial and rushed to remove his name from their founding documents.

“They rewrote their history to erase the Johnny Appleseed of British communism from it,” Mr. Flynn noted. “He started the movement at Oxford, mentored the early leaders and was the first young person on the board of the British Communist Party.”

According to the biography, Meyer espoused conservative views by 1950. He was one of several former communists who helped pundit William F. Buckley found National Review in 1955.

Meyer came to embrace conservative social views through a gradual conversion to Catholicism, which he had encountered through a tutor at Oxford.

In a 1960 interview, Meyer professed a Christian belief in the Triune God and natural law.

He spent the last 17 years of his life working from his rural home in Woodstock, New York, while carrying a gun in case any of his former communist comrades came seeking revenge.

He converted to Catholicism on his deathbed, spending the last six hours of his life as a Catholic.

Mr. Flynn said the assassinations, social unrest and “moral chaos” of 1968 had pushed Meyer toward a greater concern for social order.

“What he learned was that the Communist Party didn’t mesh with the American founding,” Mr. Flynn said. “Freedom did.”

‘Libertarian-ish’

According to “The Man Who Invented Conservatism,” Meyer’s eloquent public voice helped transform the right from a loose alliance of groups opposed to Franklin Roosevelt’s social spending policies into a political movement of common beliefs.

As a longtime columnist and book review editor, he recruited literary giants such as Theodore Sturgeon to write for National Review.

“He was libertarian-ish,” Mr. Flynn said. “He thought the federal government’s three functions were to enforce the law, defend the country and adjudicate disputes in court. Beyond the police, courts and army, he thought the government became unnatural by invading the private sector.”

Meyer outlined his idea of fusionism in the 1962 book “In Defense of Freedom,” which gradually came to define a new breed of conservative Republican politicians.

Mr. Flynn noted that GOP candidates Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan credited Meyer’s ideas with helping them win elections in the 1960s.

“It’s one of the few books that became essential reading for conservatives,” Mr. Flynn added. “It seemed like everyone who read it became a conservative magazine editor or started a conservative think tank.”

Ultimately, Mr. Flynn hopes his new biography will teach conservatives about their history and tradition.

“I don’t want to write about saints,” he said. “I want to write about sinners who have many friends and live colorful lives, and Frank Meyer had the most exciting life of anyone in the conservative movement.”

Mr. Flynn acknowledged that Meyer’s ideal of unity has “frayed some” under the ever-shifting populism of President Trump’s “Make America Great Again” policies.

He said conservatives could still learn from Meyer’s emphasis on principles over personality as they seek a way forward politically after Mr. Trump’s second term ends in 2029.

“I think Meyer would admire Donald Trump on foreign policy and possibly immigration,” Mr. Flynn said. “He would be more skittish about increasing the size of government, raising the debt and lowering interest rates.”

• Sean Salai can be reached at ssalai@washingtontimes.com.