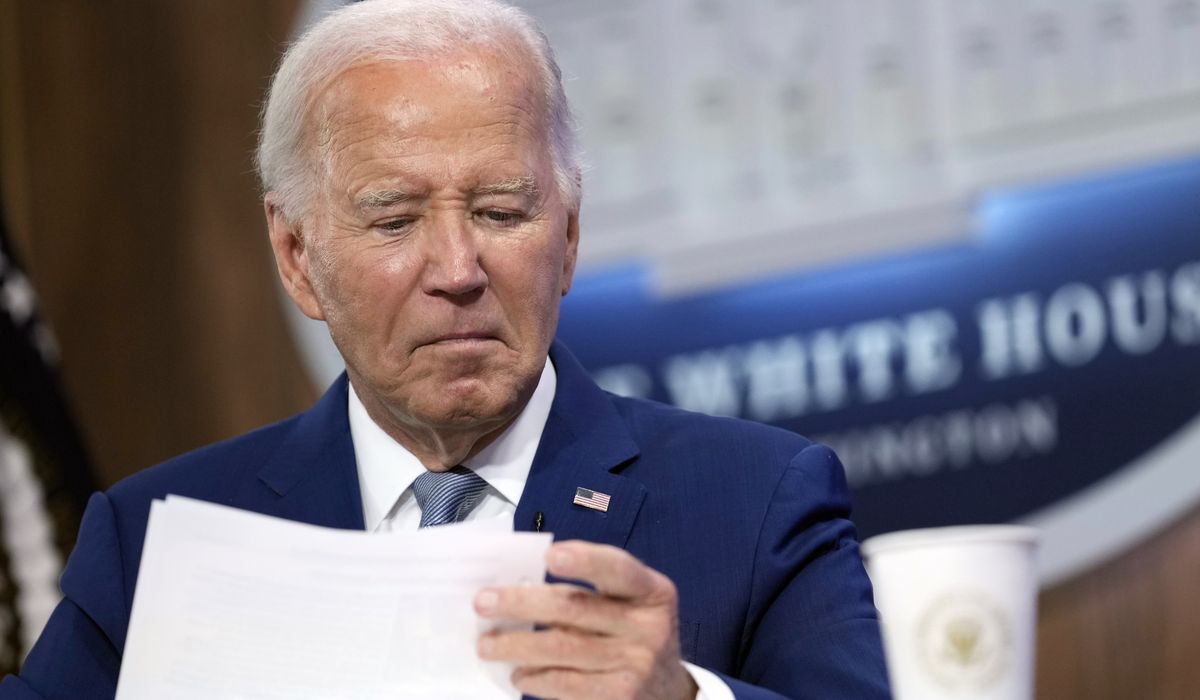

President Biden introduced a new “potential marriage penalty” into the tax system when he ordered the IRS to start doing more audits of higher-income Americans, according to the agency’s inspector general.

In convincing Congress to give him tens of billions of dollars for the tax agency to conduct audits, Mr. Biden promised that agents would focus on those making $400,000 or more.

But the way the Treasury Department wrote the guidance treats all “households” the same, meaning a family where both spouses each $220,000 faces a higher chance of an audit than a single man who earns $390,000.

The marriage penalty is one of a host of issues the IRS is working through as it plans to carry out Mr. Biden’s audit orders and spend the tens of billions of dollars that Congress allocated for the effort, the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration said.

And TIGTA said time is running short on making those decisions.

“The IRS believes it has more time to work with the Treasury Department to finalize the audit coverage rate. However, given the complexity of developing the methodology and that FY 2025 is only a few months away, we believe the IRS needs to expedite the finalization of its plan to comply with the Treasury Secretary’s Directive,” the inspector general said.

Mr. Biden promised that those with incomes under $400,000 won’t see an increase in their chances of being audited, while those above $400,000 will.

Figuring out what that means, though, isn’t simple.

For one thing, the IRS is trying to figure out how to measure who falls into which category.

The agency is wary of using taxpayers’ reported total positive income, or TPI. The agency figures some people right at the line will play shenanigans to end up below it.

“IRS officials stated that they are not following their standard approach to calculate audit coverage because they want to have the flexibility to audit taxpayers who might be incentivized to take advantage of higher audit rates of taxpayers with TPI at or above $400,000 by reporting incomes below that amount,” the inspector general said.

Another question is what the historical baseline will be for the comparison of future audit rates.

On that measure, the IRS has taken a decidedly pro-taxpayer approach and picked as the baseline the tax year 2018, when audits were “abnormally low,” the inspector general said. Just a third of a percent of those reporting income under $400,000 were audited, or nearly 40% fewer than the previous tax year.

The inspector general attributed that to years of budget cuts and the pandemic, which hindered operations in 2020 and beyond when the 2018 audits were taking place.

Then there’s the marriage issue.

The inspector general said there will be instances where combining a married couple’s income puts the household above $400,000, but individually both persons would both be below that level.

“The potential marriage penalty exists because the threshold for married couple households is not double the amount allowed for single filer households, i.e., for married couples filing jointly the TPI threshold does not increase to $800,000, thus increasing their chances of an examination,” the audit found.

IRS officials told the inspector general they were bound by the Treasury Department’s 2022 guidelines, which did not distinguish between married joint filers and single-filer households.

The agency also said the $400,000 threshold without marriage distinctions will make it easier for the agency to track its own progress.

But the IRS said it hasn’t made any final decisions.

Grover Norquist, president of Americans for Tax Reform, said Mr. Biden could settle the issue quickly, if he wanted.

“The president can make a phone call tomorrow and change this,” he said. “They work for [Treasury Secretary Janet] Yellen. Yellen works for the president.”

Mr. Norquist, who has battled Democratic presidents over tax changes for decades, said the administration is intentionally being vague about what it’s trying to do.

He said for Mr. Biden to realize the kind of revenue he expects from more aggressive audits, he would need to go after small-business owners, and fuzziness about the targets allows him to do it while minimizing the political price.

“Taxes don’t go away and they do trickle down to hit everybody because that’s where the money is,” he said.

The Inflation Reduction Act, a budget-climate law that Democrats powered through Congress in 2022, supercharged the IRS with $80 billion in new funding, to be spent over a decade.

Republicans have forced some of that money to be recaptured, leaving about $57 billion available for modernization, better taxpayer services and more audits.

The Treasury Department didn’t respond to inquiries for this story.

IRS officials didn’t address the marriage issue directly but said in response to questions from The Washington Times that they have made significant strides in following Mr. Biden’s directives to use the 2022 funding to go after high-income returns.

The IRS has already sweated $1 billion out of millionaires with overdue tax bills, and is eyeing more action against tax avoiders, large corporations and complex partnerships.

“At the same time, the IRS is taking steps to refine audit tools to avoid burdening those taxpayers who play by the rules and add more fairness to address audit disparities among lower-income taxpayers, including Earned Income Tax Credit recipients. As the IRS continues to work to formalize its methodology for audit rate reporting, our focus on high-end enforcement will continue,” the agency said in a statement.

During the 10s, those audit rates declined significantly.

In 2018, those making under $25,000 saw audit rates of four out of every thousand returns. Those making between $25,000 and $500,000 saw audit rates of one or two out of every thousand returns.

By contrast, in 2010, those making under $25,000 saw rates of 10 in every 1,000. And those making between $200,000 and $500,000 saw rates of 23 per 1,000 returns.

Those making $10 million or more were audited at a rate of 39 per 1,000 returns in 2018. In 2010, they were audited at a rate of 212 per 1,000 returns — a drop of 81%.

• Stephen Dinan can be reached at sdinan@washingtontimes.com.