From the blue corner, weighing in at 179 years and counting, is The Associated Press, the venerable news-gathering organization that counts itself first among equals in the White House press room.

From the red corner, hailing from Mar-a-Lago and weighing in at four weeks into his second term is President Trump, keen on taking the media down and figuring he’s finally found his opening.

Amid all of the fights the new president has picked so far, his feud with AP is the spiciest: one part petty, one part subversive and one part pure power politics.

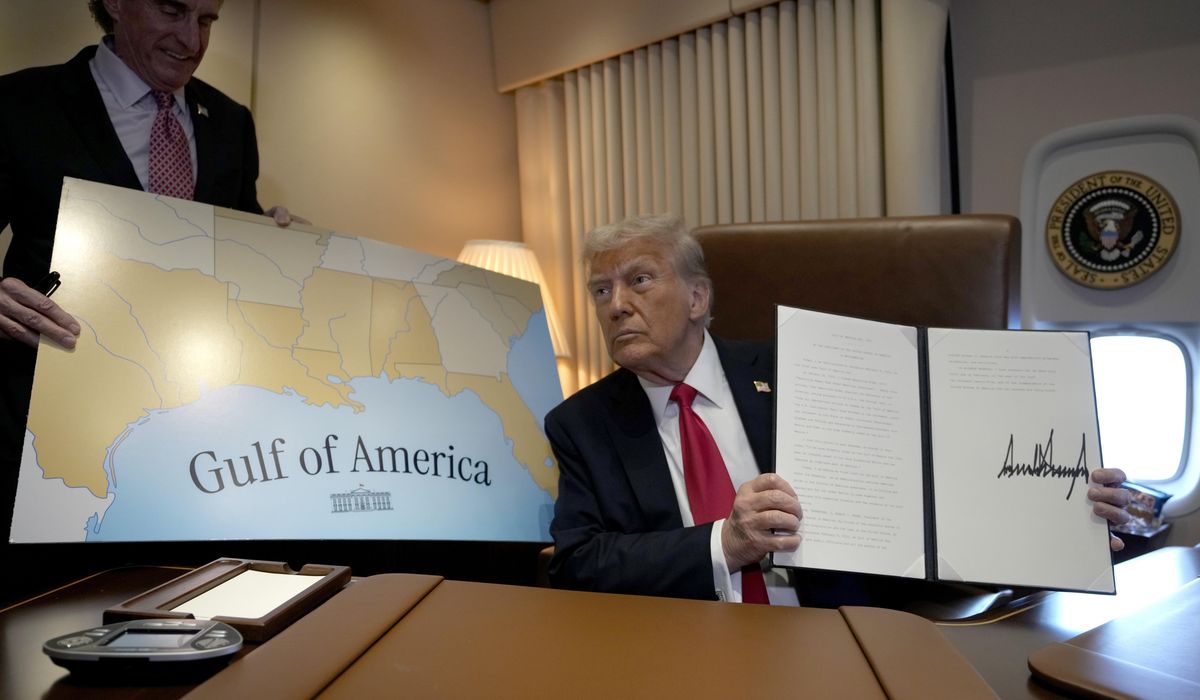

Mr. Trump says AP has forfeited its special solicitude from the White House by refusing to use the “Gulf of America” to refer to the body of water east of Texas, west of Florida and south of Louisiana. The AP is sticking with the “Gulf of Mexico,” saying it won’t be bullied into changing.

The result is that the White House has blocked AP reporters from a place in a select group of reporters that tracks presidential doings on Air Force One and in the Oval Office. Like the U.N. Security Council, most news outlets in that group rotate, though AP and a couple of others are considered permanent members.

The AP’s defenders say the blockade is an assault on the First Amendment because it’s a government actor punishing the news outlet for its ideological views.

The dispute threatens to break new ground in president-press relations, and could force the courts to weigh in and write law where it’s always remained somewhat vague.

Some legal scholars said they’re not certain which side would prevail.

“I think that for Air Force One and Oval Office appearances, the best I can say is that the First Amendment analysis is unsettled,” Eugene Volokh, a prominent First Amendment expert, wrote on his influential legal blog, The Volokh Conspiracy.

He said presidents have long enjoyed freedom to select whom to give an interview to, or whom to call on during a gathering of a group of reporters. No news outlet would win a lawsuit arguing a right to be called upon.

But courts have also held that public officials can’t exclude news outlets from events that are generally open to the press, at least when that exclusion is based on ideological or viewpoint differences.

Floyd Abrams, a famed First Amendment lawyer, told The Washington Times he thinks AP has the better argument here.

“The issue of when a press entity has a constitutional right to attend a White House event is sometimes difficult,” Mr. Abrams said. “But when it is clear, as it is in this situation, that AP is being barred from being present solely because it has made a journalistic decision with which the president disagrees. It has a strong First Amendment argument that it may not be excluded.”

Aaron Terr, director of public advocacy at the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, said the White House’s reason for denying access matters. He said cutting off access that AP previously enjoyed violates the First Amendment.

“The AP — a major news agency that produces and distributes reports to thousands of newspapers, radio stations, and TV broadcasters around the world — has had long-standing access to the White House. It is now losing that access because its exercise of editorial discretion doesn’t align with the administration’s preferred messaging,” he wrote.

Mr. Trump this week said he’s committed to the fight.

“We’re going to keep them out until such time as they agree that’s the Gulf of America,” Mr. Trump told reporters. “We’re very proud of this country and we want it to be the Gulf of America.”

The president spoke at a press conference at Mar-a-Lago, his Florida home. The AP said two of its reporters were denied access to the event and had to report their stories from a television feed.

Mr. Trump said his problems with AP go beyond the naming dispute, and he sees the fight as a matter of reciprocity.

“They’re not doing us no favors and I guess I’m not doing them any favors. That’s the way life works,” he said.

Mr. Trump pointed out that the official federal designation is now “Gulf of America.” He said AP “just refuses to go with what the law is.”

The AP’s influential style guide sets the word choices for much of America’s media. That makes it the 800-pound gorilla of the press corps — and obvious target for Mr. Trump, who in his second term has shown a willingness to strike at targets once thought beyond reach.

The AP says its reticence over renaming the gulf is due to the age of the name, dating back 400 years, and to the news wire’s own global reach. It said its names must be “easily recognizable to all audiences.”

But it did adopt another of Mr. Trump’s renaming decisions, which reverted North America’s tallest mountain from Denali — an Obama-era change — back to Mt. McKinley. The AP said that since the mountain “lies solely in the U.S.” and Mr. Trump has authority to change federal geographic names, they would follow him.

Mr. Trump isn’t the first to fight the press over access.

Presidential campaigns have booted reporters out of their airplane rotation — including The Washington Times and New York Post, which were ousted by the Obama campaign in 2008.

And in the White House, the Obama team tried to block Fox News from its space in the pool of reporters for an interview with a top official.

“We’ve demonstrated our willingness and ability to exclude Fox News from significant interviews,” an Obama spokesperson said at the time.

Mr. Trump, in his first go-around in 2018, also moved to revoke the press pass of Jim Acosta, then at CNN, after a testy press conference exchange.

A federal judge ordered the credential restored, citing “due process” concerns rather than First Amendment issues.

The AP has not lost any credentials, but has lost specialized access.

The Washington Times is part of the rotating group of reporters that covers the White House. The Times has signed a letter objecting to the White House’s treatment of the news services.

• Stephen Dinan can be reached at sdinan@washingtontimes.com.