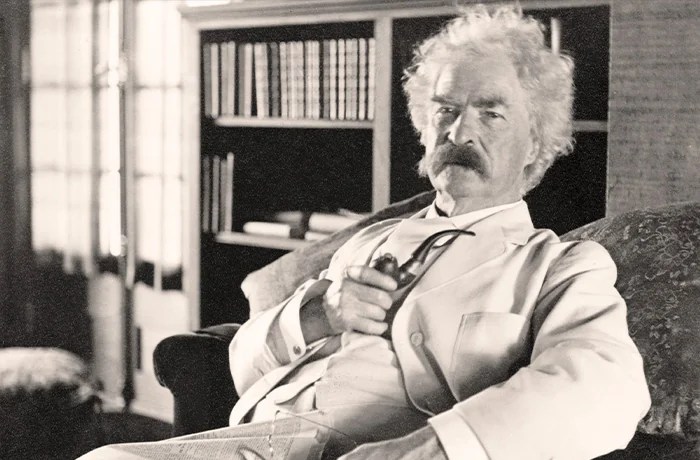

Samuel Langhorne Clemens, better known as Mark Twain, was one of America’s finest writers, essayists, and humorists. His literary masterpieces, including The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, are timeless classics. They’ve engaged legions of readers and sparked the imagination of countless young minds.

Recommended Stories

- John Cena’s empty throne

- Unwinding the Gauguin myth

- Fuzzy Math: Several House districts could be redrawn before 2026 elections

William Faulkner’s description of Twain as “the father of American literature … the first truly American writer, and all of us since are his heirs” is the type of high praise that few writers will ever achieve. Alas, the same joyous words cannot be easily employed when the conversation shifts from Twain the writer to Twain the man.

Ron Chernow’s exceptional biography, Mark Twain, devours the life’s work of the perfect American writer and lays bare the unfortunate reality of an imperfect American life. The renowned author of award-winning books on George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and J.P. Morgan’s financial empire has never tackled a subject quite like this. Clearly a massive undertaking by Chernow, the result is an exquisitely written, deeply researched volume about an intriguing, complex, contradictory, intelligent, and often exaggerated literary stylist.

“To portray Mark Twain in his entirety,” Chernow noted, “one must capture both the light and the shadow of a beloved humorist who could switch temper in a flash, changing from exhilarating joy to deep resentment.” Indeed, he was a “fascinating, maddening puzzle to anyone trying to figure him out: charming, funny, and irresistible one moment, paranoid and deeply vindictive the next.” In the author’s view, “perhaps we should not be surprised that America’s funniest man harbored ineffable sadness and displayed a host of contradictions.”

Born on Nov. 30, 1835, in Florida, Missouri, he was the sixth of seven children born to John Marshall Clemens, a lawyer, and Jane (née Lampton), a natural-born storyteller and inspiration for Tom Sawyer’s Aunt Polly. They would move to Hannibal, Missouri, located along the Mississippi River, when Twain was 4.

His father unexpectedly died in 1847. An understandably emotional moment for young Twain, it led to a dramatic change in the course of his life and American literature. He left school and went to work as a “printer’s devil,” or apprentice printer, at the Hannibal Gazette and Missouri Courier. It was during this time that he “betrayed his first spark of literary interest when he supposedly scooped up a scrap of paper lying in the street,” which was from a biography of Joan of Arc. So began a lifelong love affair with reading and accidental entry into writing for the Hannibal Journal, owned by his brother Orion.

Mark Twain explores a multidecade journey of a man who would become one of the most famous Americans, a saga containing highs, lows, and occasional bumps in the road. Prepare to learn everything you always wanted to know about Twain but were afraid to ask.

His relationship with his family was endearing. Twain’s wife, Olivia, or “Livy,” was the love of his life. They maintained a “marriage of mutual adoration” that never wavered. He had a deep love for his three daughters, Clara, Jean, and especially Suzy, the eldest, who he found to be “full of gumption and poetry, fire and intelligence.” In spite of this loving family environment, Twain did something peculiar after Livy died in 1904. He became infatuated with young, teenage girls he called “angelfish.” Chernow suggested these were “latent tendencies … not exactly concealed.” Indeed, most people “regarded this not as the sinister hobby of a lecherous old pedophile, but as the charming eccentricity of a sentimental old widower.” Whatever the case, it leaves a bad taste in your mouth.

Twain’s personality blew hot and cold throughout his life. He’s portrayed as a delightful character in certain passages, displaying an undeniable wit, charm, and self-deprecating nature. At the same time, he was fiercely opinionated, pessimistic, temperamental, and not nearly as humorous in person as he was in the written word. Twain, in Chernow’s view, was a “type of author hard to imagine today: a man born without an inner censor.” He had a “whimsical, if sometimes cruel, eye,” “curmudgeonly streak,” and was “unconstrained by modern issues of fairness or political correctness.”

What about politics? It certainly ran in his family: Orion became a Republican politician and the first and only secretary of the Nevada Territory. Twain started off relatively apolitical, although he had some leftish positions, such as supporting labor and being anti-war. “Too free a spirit to toe any party line,” Chernow wrote in one chapter, “he poured abuse on the corrupt machines running both parties.” Nevertheless, Twain leaned Republican for most of his life, albeit on the liberal and radical side of the party, which isn’t to say that he agreed with everything the GOP supported. His political thinking transformed at one stage due to “shifting views” about President Andrew Johnson, “whose coddling of southern white planters ran counter to the Radical Republicans’ desire to empower Blacks in the South.”

This was something that Twain, a civil rights supporter, would not stand for. His father’s family had been “fully enmeshed in slavery,” and he had “his brain stuffed with early stereotypes.” These early and ugly beliefs were quickly washed out of his system thanks to his “boyish affection for Black people” and young black playmates. His childhood church’s “unswerving endorsement of slavery” served to weaken his faith. Twain had many black friends and allies. This included George Griffin, a butler born into slavery, and John Lewis, a free black man who was the influence for Jim in Huckleberry Finn, and who became a trusted ally after he “rescued the runaway carriage at Quarry Farm.” An iconic 1903 photo of Twain and Lewis sitting together at the farm remains a powerful and poignant image in the post-Civil War period.

Twain was understood as a master of political satire, but his writing also had a distinctly serious side. It was visible in his work for the Buffalo Express, which he co-owned. He critiqued the lynching of a black man unjustly accused of raping a white woman in Memphis and blasted the abhorrent mistreatment of Chinese immigrants in cities such as San Francisco. He also had “evident warmth towards Jews” and wrote passionately about the injustices of the Dreyfus affair. In spite of some borderline stereotypical writing about Jewish vendors in Life on the Mississippi and occasionally associating Jews with “business cleverness,” Chernow wrote that “Twain always meant well toward the Jews and was quick to take a stand in their defence.”

REVIEWED: ‘TWELVE POST-WAR TALES’ BY GRAHAM SWIFT

Even Twain’s great works of fiction and nonfiction had their own unique stories to tell. The Innocents Abroad, a humor-laced travel book published in 1869, was a massive financial success. Ironically, Chernow suggested it “proved a misfortune for Twain that his first complete book was the best-selling book of his lifetime, for it set a benchmark he could never match.” There’s also the “paradoxical fate of Huck Finn,” in which Twain’s “most searing indictment of racism has itself been accused of racism.” The brilliant 35 aphorisms that made up Pudd’nhead Wilson’s Calendar, Chernow suggests, “took the tradition of uplifting maxims minted by Benjamin Franklin and gave them a hilariously cynical twist.” And the unforgettable Tom Sawyer, with a “quietly subversive spirit” like The Prince and the Pauper, shows that “ordinary people have a native visor and intelligence often lacking in their supposed betters.”

Chernow’s titanic study of Twain is a literary triumph. No stone has been left unturned. At the same time, this engrossing book will likely leave some readers betwixt and between what they want to accept about this master of prose – and what they must admit about the flawed steamboat pilot who once travelled the watery path of Ol’ Man River.

Michael Taube, a columnist for the National Post, Troy Media, and Loonie Politics, was a speechwriter for former Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper.