At one point in his recent interview with Bari Weiss of The Free Press, Woody Allen insisted that his works were, at best, weakly autobiographical.

Recommended Stories

“The characters in my movies, yes, have certain traits and certain obsessions that I have. But in life, they’re within normal bounds, they’re in rational bounds,” Allen told Weiss. “The characters in the movies are hugely exaggerated because I’m trying to make them funny and preposterous, and put them in situations that are dramatic and farcical.” He dismissively says that viewers note that a character of his in a movie drives a car, and that he drives a car in life, so he is given the reputation of being an autobiographical filmmaker.

This argument, part and parcel of Allen’s general strategy to deflect attention from his considerable accomplishments, is not persuasive. He has drawn upon his 89 years on Earth consistently, obsessively, and profitably. He has more in common with his characters than the fact that he and they drive cars. He aired his annoyance at being associated with his “early funny” films in Stardust Memories. He offered a paean to his boyhood movie-going in The Purple Rose of Cairo and to his boyhood radio-listening in Radio Days. In too many films to list, he wrote and cast himself as the love interest to Diane Keaton and Mia Farrow, women who were, at times, his actual love interests. Some of his films only make sense when considered in the context of his autobiography, including Husbands and Wives, which alluded to fissures in the Allen-Farrow union that culminated in Allen’s affair with Farrow’s grown adopted daughter, Soon-Yi Previn, and Farrow’s subsequent charge that Allen abused their 7-year-old adopted daughter, Dylan (an accusation he has persistently and persuasively denied).

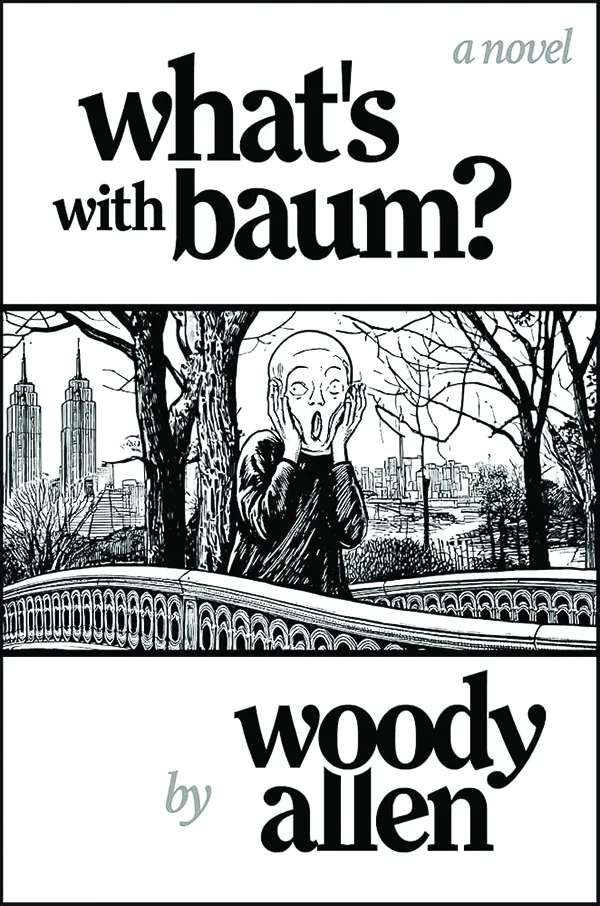

Yet, none of Allen’s 50-plus films are as unmistakably or angrily autobiographical as his new novel. What’s With Baum? has, at its center, Asher Baum, a nervous, morose Jewish writer who shares more than a few characteristics with his creator. “He was on a roll with his writing but sadly it was a roll downhill,” writes Allen, whose career has followed approximately the same trajectory in the MeToo era. “If he suffered from anything, it was hypochondriacal panic attacks where he saw the abyss in every mole, cough and hangnail,” writes Allen, who is well known for a similar attitude of alarmism when it comes to his physical well-being. And who could fail to see a reference to Allen’s relationship to Farrow when he writes of Baum’s fraught third marriage: “Fourteen years that began with dinner dates and flowers had through the drip, drip, drip of broken dreams and things said that could not be taken back formed a critical mass, ready to detonate.”

In fact, What’s With Baum? so thoroughly reconstitutes some of the people and incidents of Allen’s life that, in the spirit of Frank Costanza on Seinfeld, it might be called an airing of grievances. Take, for example, Baum’s third wife, Connie, who shares with Farrow a Beverly Hills background, a movie star mother, and a constantly alluded to love of the country, which Baum (like Allen) finds completely unappealing. “Who wants to live where you need a flashlight to take a walk after dinner?” writes Allen, adding that Baum found the stars visible from Connie’s country estate to be less than enchanting: “My god, the thought of those numbers, everything measured in light years. And the whole megillah with huge hunks of rock aimlessly amuck in pointless violence.” Robert Frost, he is not. He is said to love Grandma Moses, “despite her subject matter.”

Of course, Allen fictionalizes Connie by giving her small characteristics, such as “jet-black hair” and no siblings, that differentiate her from his former companion. (Farrow is famously blonde and one of eight children.) Yet these fine distinctions matter less than the large overlaps between life and art that Allen seems intent on making, none more so than Connie’s unfathomably vast and deep love for her grown son from an earlier marriage, the insufferable Thane — an invigoratingly hateable literary creation. Allen writes of Baum’s disgust with the Thane-Connie twosome like a man possessed. “Connie adored Thane and in his eyes she was perfection,” he writes. “He would do anything to please her, to win her love which he already had but nevertheless reveled in winning it over and over.” For his part, Baum has been repulsed by Thane’s supercilious precocity since first meeting him — appropriately enough, at the New Year’s Eve party where he also made the introduction of his mother. There, 9-year-old Thane, dressed in a Ralph Lauren blazer and slacks, accidentally on purpose spills his drink on Baum’s Saks sport coat. “It had become clear to him,” Allen writes, “that it was a package deal and if you wanted Connie, you bought Connie and Thane.”

Readers will be forgiven for wondering whether, in sketching the character of Thane, Allen had in mind his own biological son with Farrow, the hugely successful MeToo journalist Ronan Farrow. Allen seems to encourage this impression by giving Thane the profession of writer. To Baum’s everlasting dismay, Thane — “that little coddled egg, that Midwich Cuckoo” — has written a bestselling novel that is being whispered as a shoo-in for literary prizes. Hmmm.

Of course, Allen has always been very good about not exempting himself from parody, and in that spirit, he leaves Baum open for satirical scrutiny. For example, Baum’s incessant dissatisfaction with his wife and stepson is itself a source of humor. A whiner in the usual Allen manner, Baum cannot even bring himself to see eye to eye with Connie in the matter of transportation: “Baum rolled on in his Volvo, a car he found charmless but that Connie thought extremely safe and efficient on the country roads.” That Allen, in describing Baum’s state of mind, incorporates one more unnecessary jab at Connie’s love of the rural life, is proof that he recognizes his character’s limited perspective — good. Similarly, Baum’s objection to Connie’s concern about getting proper medical care for Thane when his appendix bursts overseas comes across as needlessly churlish: “You would have thought they were in the remotest jungles of the Amazon with only medicine men,” Allen writes of Connie’s panic, assuming Baum’s perspective but not, one senses, entirely uncritically. And Allen sees no good reason for Baum’s overall state of ceaseless dissatisfaction: “No, there was no reason for growing up with a fear of loneliness because he was never left alone, never traumatized, never dumped with maids, never abandoned, never lost on the subway.”

Yet, in the fullness of time, the novel works to confirm, not complicate, Baum’s estrangement from Connie and disgust for Thane, especially after Baum is tipped off to a career-destroying controversy regarding Thane’s gushed-over book. “What a turn of events!” Baum thinks to himself. “To unmask this phony genius as a hustler, a fake, a scammer.” Naturally, Thane’s reaction to the uncovering, to say nothing of Connie’s, further validates Baum’s low opinions of them.

All of this takes place against the backdrop of allegations that Baum behaved inappropriately with a young female interviewer, which Baum denies (or at least attempts to explain as a gentlemanly kiss followed by an ungraceful fall) even while it scandalizes the presumably woke underlings at his publisher. Of course, one cannot read these passages — “In today’s culture an accusal is as good as a conviction” — without thinking of the allegations lobbed at Allen (and his subsequent booting from polite society, including the original publisher of his 2020 memoir, Apropos of Nothing). When Allen writes that Baum “was certain everyone walking to the subways and buses or hailing taxis” knew about the charges against him, it is impossible to imagine that Allen is not writing from experience. That Baum exposes Thane amid his own downfall gives the novel a tone of schadenfreude: If Baum is going to go down, he wants to take his enemies with him. In his interview with Weiss, Allen speaks as though he has little concern about his reputation, but no one who is actually indifferent could write such a thinly disguised account of his own tribulations.

REVIEW OF ‘MOTHER MARY COMES TO ME’ BY ARUNDHATI ROY

As a work of literature, What’s With Baum? has the brisk, unfussy feel of an Allen film, especially one of the many that hovers at or under 90 minutes. There are no chapters, and the action is largely cinematic. It is easy to imagine the abundant supporting characters (Baum’s brother, Baum’s agent, Baum’s ex-wives) as starry cameos on screen. The writing is as strong and natural as Allen’s short stories, which once substantially enhanced the pages of The New Yorker. If I were to compare the novel to any single Allen movie, it would be Deconstructing Harry, whose lead character, a writer, gets into a boatload of trouble for repurposing things from his life for his fiction.

Don’t let anyone tell you that Woody Allen is not an autobiographical artist, including Woody Allen.

Peter Tonguette is a contributing writer to the Washington Examiner magazine.