In the pantheon of 19th-century freedom fighters, abolitionists like Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison share space with the martyred President Abraham Lincoln and the emancipated writer Harriet Tubman. But Charles Sumner, the Massachusetts senator who prodded Lincoln into signing the Emancipation Proclamation and introduced the Thirteenth Amendment and landmark civil rights legislation, has nearly been forgotten. At least, until now.

Recommended Stories

- Review of ‘The Price of Victory’ by N.A.M. Rodger

- Review of 'Tomorrow Is Yesterday: Life, Death, and the Pursuit of Peace in Israel/Palestine' by Hussein Agha and Robert Malley

- Inside Scoop: Unpopularity plagues Democrats, media fail Kirk, candidate quality matters

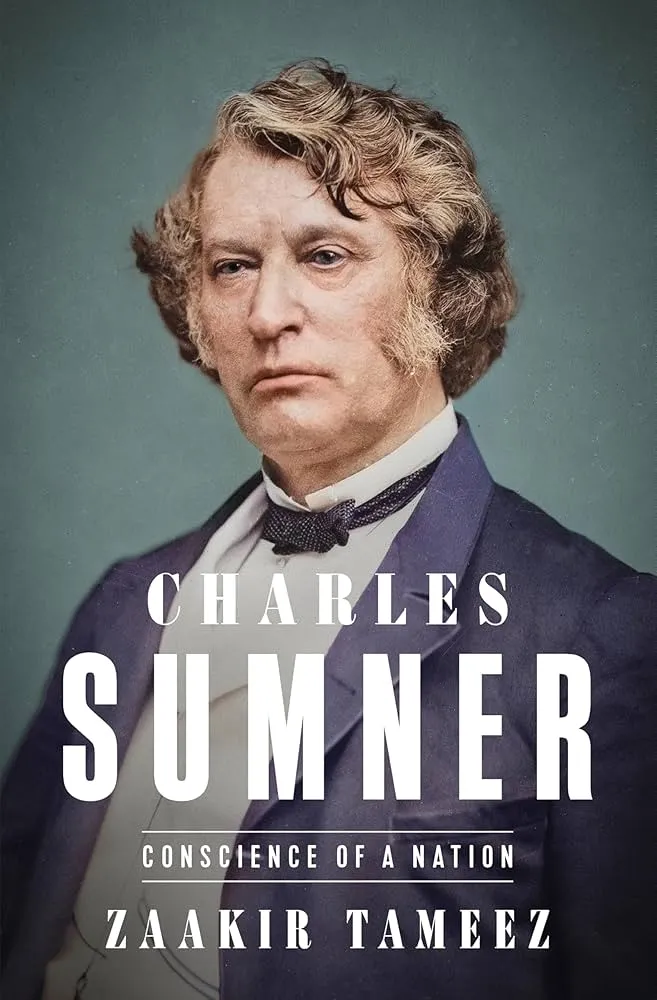

In Charles Sumner: Conscience of a Nation, the first full-length biography of Sumner in more than two generations, the writer Zaakir Tameez resuscitates his subject’s reputation as a largely derided moralistic hothead and restores him to his rightful place as “the most famous civil rights leader of the nineteenth century.” An absorbing and sensitive survey of an enigmatic character, Tameez’s book adeptly captures the many contradictions of the tumultuous life of a truly great, flawed leader.

Sumner was born on Beacon Hill in 1811 to Charles Pinckney Sumner and Relief Jacobs Sumner, both second-generation Bostonians. Pinckney embraced abolitionism early in life when he visited Haiti after a bloody late 18th-century uprising ended slavery on the island. A resident of a mixed neighborhood considered part of “Black Boston,” he may have been the first to refer to black Americans as “people of color.” And he once prophetically opined on slavery, in the early 1830s, that “our children’s heads will some day be broken on a cannon-ball on this question.”

But Charles Sumner, whose parents and grandparents were not wealthy and often even impoverished, did not grow up with a silver spoon in his mouth. A bright student, he won the equivalent of a full scholarship to the prestigious Boston Latin School and received his bachelor’s degree from Harvard. After a brief course of self-study, he returned to Cambridge to study law under the tutelage of the legendary Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story, one of Pinckney’s childhood friends. “I feel proud to think,” Story told him, “that I have, in some sort, a heritable right to your friendship.” Story and his colleagues invented the now-standard pedagogical practice of “cold-calling,” and Tameez reckons that “Sumner was among the first students to benefit from it.”

After completing his legal education in 1833, Sumner struggled to ignite his private legal practice. At Story’s invitation, he joined the Harvard Law faculty and shadowed the justice as he heard arguments in Washington. He also met Garrison, the outspoken abolitionist who published The Liberator. And on a visit to France, he encountered black and white students attending university classes side by side. “My intercourse with men in Europe convinces me,” he wrote, “of the necessity of … abolishing slavery.”

Back in Boston, he crossed paths with Longfellow, Dickens, John Quincy Adams, and even Tocqueville, who proclaimed that he “speaks like a prophet.” And while his law practice continued to flounder, he gained recognition as a learned, eloquent, and impassioned speaker in favor of important causes. Along with fellow Bostonians Charles Francis Adams and Richard Henry Dana, Sumner formed the “Conscience Whigs,” who began railing against slavery. He labeled the ability to amend our founding document to bar enslavement “an important element, giving to the Constitution a progressive character.”

By 1848, their movement had coalesced into a new party, the Free Soilers, which claimed 30% of the vote in the Northeast, and through Byzantine negotiations in the Massachusetts legislature, Sumner became a U.S. senator in 1851. His maiden oration comprised a blistering denunciation of the Fugitive Slave Law in which he invoked Augustine’s injunction that “an unjust law does not appear to be a law.” He channeled his moral outrage into stemming the expansion of slavery, which meant fiercely resisting the Kansas-Nebraska Act introduced in 1854 by Sen. Stephen Douglas, an Illinois Democrat and the tribune of “popular sovereignty.” “Believing in God, as I profoundly do,” Sumner thundered on the Senate floor, “I cannot doubt that the opening of an immense region to so great an enormity as slavery is calculated to draw down upon our country His righteous judgments.”

While the act passed, it also triggered the formation of the Republican Party, which aimed principally to prevent slavery from spreading westward. In 1856, the fledgling party nominated John Fremont for the presidency, but the Know-Nothing candidate Millard Fillmore split the anti-slavery vote, ushering James Buchanan into the White House. The next year, the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision unleashed a torrent of support for the anti-slavery movement, which both Sumner and a rising country lawyer named Abraham Lincoln channeled into electoral success. The former delivered a rousing oration in the Senate entitled “The Barbarism of Slavery,” in which he framed the vexing debate as a “solemn battle between Right and Wrong; between Good and Evil,” while the latter won a sweeping electoral victory in 1860 that included all the Northern states and 40% of the popular vote in a four-way race.

As the country spiraled toward civil war, Sumner remained steadfast in his uncompromising dedication to abolitionism. “Much as I desire the extinction of Slavery, I do not wish to see it go down in blood,” he said. “And yet the existing hallucination of the slave-masters is such that I doubt if this calamity can be avoided. They seem to rush upon their destiny.” He fell out with his friends Charles Francis Adams and William Seward, then Lincoln’s secretary of state, over their efforts to negotiate a peaceful resolution to the budding secession crisis short of ending slavery. As the newly appointed Senate Foreign Relations chairman, Sumner played a seminal role in tightening the Union’s fraying ties to England and France during the war, which he deemed “a continuation of the other,” referring to the War of Independence. He also extended official American recognition to Haiti and Liberia, the first independent black countries in the world.

Sumner also forged a complex but ultimately rewarding wartime friendship with Lincoln, who referred to his fiery colleague as “just my idea of a bishop.” For his part, Sumner regarded Lincoln as “a deeply convinced and faithful anti-slavery man,” even if the president delayed his Emancipation Proclamation until several years into the war. As Sumner introduced into the Senate what would become the Thirteenth Amendment and popularized the expression “equality before the law,” Lincoln won a landslide reelection. But while the two squabbled over Reconstruction legislation that Sumner filibustered as insufficiently aggressive, they reconciled at Lincoln’s second inaugural and a month later in Richmond, where the Confederacy had just surrendered. Days afterward, John Wilkes Booth performed his act of perfidy, and a weeping Sumner attended Lincoln’s deathbed.

Things worsened when Andrew Johnson assumed the presidency, as Sumner clashed with the White House and his Republican colleagues alike. “What is Liberty without Equality? What is Equality without Liberty?” Sumner thundered on the Senate floor, as the chamber debated the Fourteenth Amendment in 1866. “One is the complement of the other. The two are necessary to round and complete the circle of American citizenship.” Through implementing Reconstruction, Sumner strove valiantly and successfully to realize the Constitution’s promise, nothing less than a second founding of the country. Along the way, he facilitated the purchase and naming of Alaska.

After falling out with President Ulysses S. Grant over matters political and personal, Sumner contemplated leaving the Senate, but not before pressing important civil rights legislation designed to integrate vast sectors of American society. Regarding schools, achieving “the promise of the Declaration of Independence” necessarily entailed access to “the same teachers, in the same school-room, without any discrimination founded on color.” Yet his strength and his stature had faded. Stripped of his committee chairmanship, censured by the Massachusetts legislature, Sumner returned home in 1874, suffered a heart attack, and died.

Even a great man has flaws. Sumner’s insouciance bore painful consequences — literally. After a scorching 1856 speech titled “The Crime Against Kansas,” in which he likened Douglas to Lucifer, other prominent congressional Democrats to traitors and misfits, and President Franklin Pierce to a Roman dictator, congressman Preston Brooks of South Carolina savagely beat him with a cane on the floor of the Senate. A badly bloodied Sumner lost consciousness after absorbing as many as thirty blows, and the beating would affect him physically and emotionally for the rest of his life. (After Brooks died of asphyxiation a year later, at age 37, a surprisingly gracious Sumner refused to crow about the demise of his assailant. “What have I to do with him?” Sumner mused. “It was slavery, not he, that struck the blow.”)

In addition, his anger at Grant led him to support the avowedly racist Horace Greeley in the 1872 election. He alienated Frederick Douglass, who’d previously extolled him for exposing “the meanness, brutality, blood-guiltiness, hell-black iniquity, and barbarism of American Slavery.” As Tameez aptly puts it, “Sumner’s uncompromising stance was arguably admirable. But it was also self-defeating.” Or as a one-time ally put it, “He stands on a bridge, and has set fire to both ends.”

REVIEW OF ‘MIDNIGHT ON THE POTOMAC’ BY SCOTT ELLSWORTH

Tameez also reasons that Sumner “likely was a gay man who didn’t understand his sexuality,” a claim borne out by several illustrative instances, including what the author calls “romantic friendships” with Longfellow and Samuel Gridley Howe. His late-in-life marriage to the much younger Alice Hooper ended swiftly and unhappily, rendering him a bachelor for life.

Some of Tameez’s prose and arguments suffer from presentism, as when he claims that a young Sumner “continued to reflect on the privileges of being a white man,” or engaged in “radical social reform work,” or was insufficiently receptive to Native Americans and Alaskans. But his otherwise excellent biography of Sumner seems destined to become the definitive one. It’s the least that this uptight, righteous, curmudgeonly, uncompromising, honest, eloquent tribune of liberty deserves.

Michael M. Rosen is an attorney and writer in Israel, a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, and author of Like Silicon From Clay: What Ancient Jewish Wisdom Can Teach Us About AI.