Arundhati Roy dedicated her debut novel, The God of Small Things, to two people who, it was safe to assume, were her nearest and dearest: “For Mary Roy who grew me up,” she wrote, “Who loved me enough to let me go.” The other dedicatee was more cryptically designated: “For LKC, who, like me, survived.”

Recommended Stories

- Papering over ‘The Office’

- Judge's Google antitrust ruling singes but doesn’t burn search giant

- Inside Scoop: Degraded American culture, flag burning, and Cracker Barrel lessons

In her new book and first memoir, the Indian writer sheds light on those dedications. LKC is Arundhati Roy’s brother, Lalith Kumar Christopher. The pair of them “survived” a tough upbringing at the hands of their sole provider, their frequently angry and abusive mother. Roy revealed her dedication to Mary Roy was a lie: “My brother jokes that it’s the only piece of real fiction in the book.” Mary Roy didn’t love her daughter nearly enough to the extent that when Arundhati Roy left home, she didn’t see or speak to her parent for years.

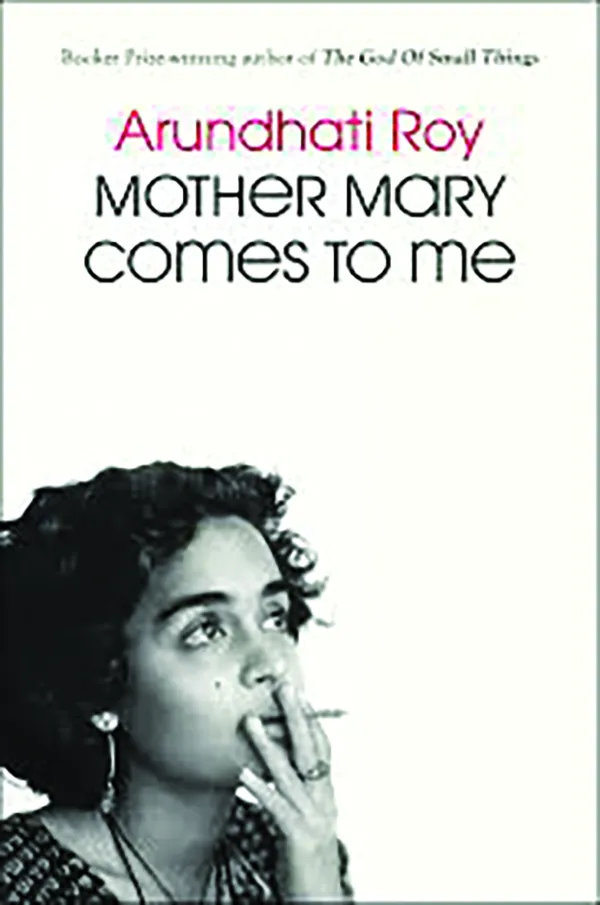

Mother Mary Comes to Me describes how Roy lived and dealt with her mother’s cruelty, and how she moved out from under her dark shadow to go it alone and forge a future as a writer. Written in the aftermath of Mary Roy’s death, Arundhati Roy set out to trace her own life and make sense of a woman she describes as “my shelter and my storm.”

Roy’s early years were marked by upheavals. When her parents separated, she embarked on a “fugitive life” with her mother and brother. Their search for stability brought them to Mary Roy’s family village in Kerala, India. The relatives they stayed with treated them as unwelcome guests, and when Mary Roy clashed with them, she took her frustrations out on her children. Then in 1967, she found a sense of purpose when she founded a coeducational school. She devoted all her energy to making it phenomenally successful — so much so that care and attention were in short supply at home. As Arundhati Roy writes, “My older sibling was a boy, and my younger sibling was a school. There was never any doubt about who our mother’s favorite child was.”

Roy turned her back on her mother’s violence and volatility when she went to Delhi to study architecture. There, she threw herself into student life and embraced her hard-won freedom. At 18, she wrote to Mary Roy with the bombshell announcement that she wouldn’t be coming home again. So insulting were her mother’s replies that Arundhati Roy stopped reading them.

From here, Roy recounts several stepping-stone stages in her life. After graduating, she gets a job at the National Institute of Urban Affairs, where she ekes out a meager salary and comes to terms with the fact that her colleague’s husband, Pradip, is in love with her. She reunites with her father, Micky — “a Nothing Man” according to Mary Roy — whom she last saw when she was 3, and who is now a frail, lame alcoholic rogue determined to wheedle money for booze through desperate schemes and spurious sob stories. She works as a scriptwriter alongside filmmaker Pradip, and the pair experience highs and lows seeing their projects come to fruition: One film is canned mid-shoot because the production company collapses; another film takes a while to get off the ground because bureaucrats who have to approve the script complain when a chunk of dialogue or a whole scene “does not show India in a proper light.” Arundhati Roy’s working relationship with Pradip blossoms into a romantic one, and the pair eventually gets married.

Following a box-office flop and the realization that she was tired of collaborating and wanted complete control of her artistic output, Roy turned her hand to a different kind of writing. The result was The God of Small Things, her sumptuous and exuberant first novel about tragic lives and illicit love. Roy’s account of her “dream ride” to publication is every aspiring writer’s fantasy. Publishers and agents read the manuscript, then bombard her with calls and contracts. The most eager London agent flies out to Delhi to meet her, and gushes, “When I read the book, I felt as though somebody had shot some heroin up my arm.” Money rolls in, plaudits pile up, and the novel bags the 1997 Booker Prize.

But the novel also ruffles feathers: religious groups, political parties, and the “moral police” take umbrage (a criminal lawyer Roy engages with declares it “obscene”). Although not blinded by the glare of publicity, Roy gradually comes to feel she is trapped in a “gilded cage” of privilege. She is afflicted by guilt at becoming a wealthy, bestselling writer in a country of poor and illiterate people, and she grows uneasy at being the more successful partner in her marriage. “My newfound fame crashed into our little love tent and jerked us around like puppets,” she confesses.

Roy’s memoir does different things extraordinarily well. It chronicles the author’s trajectory from childhood to the present day, showing her at key junctures as, in her words, “Fatherless Motherless Homeless Jobless Reckless.” It spotlights the elements of her life that informed her novels. It sets her story against a backdrop of Indian turmoil, such as wars, massacres, and assassinations, and the broad range of societal and political issues that she has confronted in her impassioned nonfiction. Throughout the book, we see Roy in various incarnations: as a daughter enduring her mother’s wrath, a student battling with her teachers, a fiercely independent, often nonconformist young woman pursuing her own agenda, and “a seditious, traitor-writer” railing against injustice.

FREDDIE DEBOER’S NOVEL APPROACH TO MENTAL ILLNESS

Best of all, though, is the mesmerizing portrait Roy offers of her mother. Mary Roy emerges as a formidable force. If it is heartening to hear of the “campaign of radical kindness” she waged in the public sphere — transforming countless lives with both her school and her tireless pursuit of equal inheritance rights for Christian women in Kerala — then it is sobering to learn how tyrannical she could be in private. Arundhati Roy recalls beatings and equally brutal verbal onslaughts: “You’re a millstone around my neck,” her mother would tell her, “I should have dumped you in an orphanage the day you were born.” Her wild temper, exacerbated by chronic asthma, triggers irrational behavior: when the family dog mates with a street dog, Mary Roy has it shot (“a kind of honor killing,” notes Arundhati Roy); when her son marries an employee at her school, she sacks the woman, boycotts their wedding, and refuses to see their baby daughter. In contrast, she attends Arundhati Roy’s wedding but spends the day criticizing her.

Roy sums up her mother neatly: “Mrs. Roy taught me how to think, then raged against my thoughts. She taught me to be free and raged against my freedom. She taught me to write and resented the author I became.” Roy would have been forgiven for harboring mixed feelings about her mother’s passing; instead, she admitted to being “heart-smashed.” She worked through her grief to produce a memoir that is refreshingly candid and illuminating. Writing it may have been painful; reading it is rewarding.

Malcolm Forbes has written for the Economist, the Wall Street Journal, and the Washington Post. He lives in Edinburgh.