The year is 2119. The world as we know it has been ravaged and reconfigured. The first catastrophe occurred in the middle of the 21st century when a Russian missile, aimed at New Mexico, fell well short of its target and exploded in the Atlantic. A series of 70-foot waves flooded Europe, West Africa, and North America. Further disasters have reduced the earth’s population to 4 billion. The global economy is broken, life expectancy has plummeted, and London, Paris, and New York are just some of the many “vanished cities.”

Recommended Stories

- On the altar of content neutrality

- Inside Scoop: Left’s radicalized allies, Kirk’s faith fueled movement, Dept. of War

- Giorgio Armani, 1934-2025

In Britain, now a “sleepy overlooked archipelago republic,” people are surviving — just. Thomas Metcalfe gets by as a politics and literature scholar at the University of the South Downs. This institution and others are perched up in hills and mountains, safely above sea level. He takes the overnight ferry to conduct research at the Bodleian library — no longer in Oxford, which was submerged, but on safer, higher ground in Snowdonia.

The subject of Thomas’s studies is Francis Blundy, who “ranked with Seamus Heaney as one of the greatest poets writing in English” in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Back in 2014, Blundy wrote a long poem dedicated to his wife for her birthday. At a private party to celebrate the occasion, he read aloud “A Corona for Vivien” to the assembled guests. After it was read, it was never heard again: Vivien possessed the only copy and didn’t want it published. Subsequent generations have been left to speculate about its content and message. They have also deliberated over where it is and why its recipient refused to share it with the world.

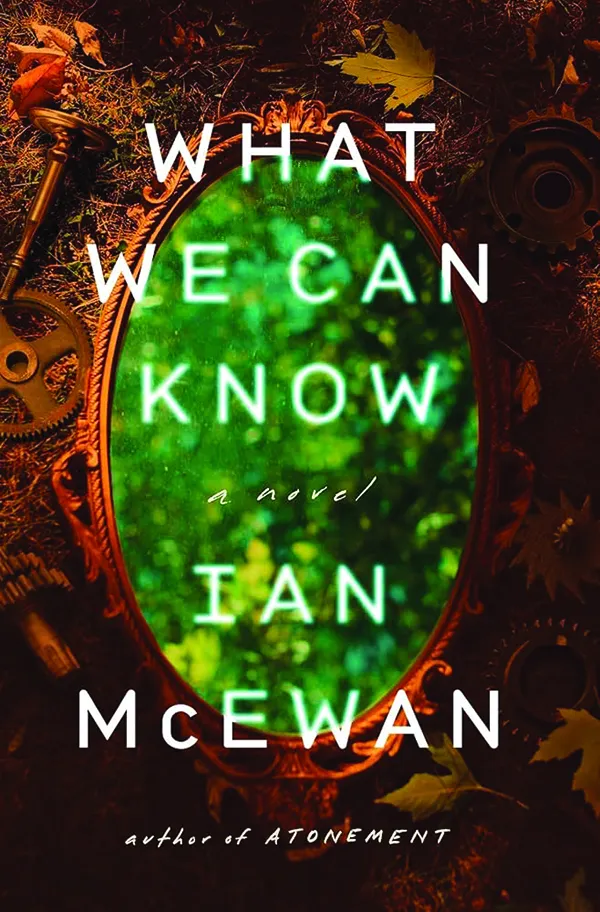

Ian McEwan’s latest novel follows Thomas as he goes in search of Blundy’s lost poem. Those who remember the last time McEwan wove narrative events around a poem will have every right to be cautious: In Saturday (2009), he strained credibility and sabotaged all carefully controlled tension when he brought in Victorian verse to influence his final act. Mercifully, What We Can Know is far more successful. It is also more ambitious: It unfolds in two timeframes, both a recognizable reality and a dystopian future. And it tackles topics as meaty as climate change, the enduring power of literature, and, as signified by the title, the breadth and the limits of knowledge.

Thomas trawls the archives and loses himself in volumes of Vivien’s journals, emails, letters, and social media. His account paints portraits of the Blundys. Vivien has given up her career as an academic to manage the household and “serve” as her husband’s secretary. Francis is opinionated, snobbish, and selfish, and enjoys his “no-finger-lifted life.” Thomas tells of Vivien’s birthday party: Francis holding forth on the false alarm that was global warming, then reading his poem from a vellum scroll, believing he is commanding the room; his guests appearing to listen raptly but in actual fact tuning out, their thoughts of recent arguments and extramarital relationships like “drifting clouds over a full moon.”

Thomas spends more time immersed in what he refers to as “my long-ago world.” He grows obsessed with Vivien, much to the chagrin of his lover, Rose. Despite his sleuth work, Blundy’s poem, “a repository of dreams,” remains out of reach. Rose tells him to call off the search for his holy grail. But then Thomas gets a lead that takes him on a voyage to an island. His expedition culminates in an excavation which yields a wholly unexpected discovery.

At this stage in the proceedings, it becomes clear that there is a lot more to What We Can Know than first meets the eye. Indeed, what we think we know is only partially true. Without giving too much away, McEwan gets up to some of his old tricks again. As with previous books such as Atonement (2001) and Sweet Tooth (2012), where the wily author didn’t so much pull the rug out from under the reader as collapse the entire floor, this novel also requires us to watch our footing.

What can and should be stated is that the novel veers away from being a literary treasure hunt in a desolate future and gradually takes the form of a more traditional but no less engrossing tale set a century earlier. McEwan switches narrator and brings in Vivien to give her side of the story of her life with Blundy, but also before and after him. She cares for her first husband, Percy, as Alzheimer’s tightens its cruel grip. She flees drudgery and misery at home by conducting an illicit affair with Blundy, which, in time, blossoms into an out-in-the-open romance and a move from Oxford to a “pastoral paradise.”

Eventually, Vivien’s narrative darkens in tone. She divulges the “corrupting secret that bound Francis and me,” one she didn’t dare make mention of in her journals. As more blanks are filled in and the mystery surrounding the poem starts to unravel, we become captivated by an intense account of passion, murder, blackmail, and guilt.

In some respects, this novel is classic McEwan. There are a couple of standout set pieces that bear the hallmarks of the Booker Prize winner. One involves a young boy abandoned on a railroad platform and picked up by a sinister stranger. The other comprises a queasy buildup to a grisly death. With the latter, it is as if the author is out to reclaim the nickname he acquired at the beginning of his career, “Ian Macabre.”

Yet the book also sees McEwan covering new ground. While he has served up alternate realities and counterfactual pasts before, this is his first real foray into the future. That future is not a high-tech, brave new world but rather a post-apocalyptic waterworld. It is boldly, if bleakly, envisioned. Thomas describes how the twin cataclysms known as the Inundation and the Derangement caused civilization to crumble. He drinks acorn coffee, uses the Nigerian-maintained internet, seeks guidance from the NAI, or national AI service, and dreams of making an Atlantic crossing, but knows that after landing in America, he would need to pay for the protection of a local warlord. “The politics were complicated,” he explains.

REVIEW OF ‘THE PRICE OF VICTORY’ BY N.A.M. RODGER

As with all good speculative fiction, the book contains sharp satirical commentary on the way we live now. Thomas’s students don’t share his fascination with the early 21st century. One decries “the morons of long ago” and “the idiocy of those times, the warming they ignored and all that, their stupid wars, the animals they killed, how skin color meant so much.” McEwan deftly highlights the precariousness of the humanities in general and literature in particular by showing Thomas’s uphill struggles teaching younger audiences to appreciate books, born out of the turmoil of the last hundred years, which are full of “beautiful laments, gorgeous nostalgia, eloquent fury.”

It becomes a little wearying encountering a host of unfaithful, bed-hopping characters. Still, they feel alive and authentic, and the drama in which they appear is richly compelling. At one point, Thomas informs us that “my duty is to vitality, to convey the experience of lived and felt life.” He speaks on behalf of his creator, who fulfills his duty with the greatest of skill.

Malcolm Forbes has written for the Economist, the Wall Street Journal, and the Washington Post. He lives in Edinburgh.