ALTURAS, California — Marin and Modoc are both California counties that start with “M,” but that’s about where their similarities end.

Marin, on the Golden Gate Bridge’s northern side within sight of San Francisco‘s often fog-swept skyline, was President Donald Trump‘s worst electoral performance in 2024 in California’s 58 counties. Modoc, in California’s rural northeast corner, was Trump’s second-best vote share.

Recommended Stories

- Greene and Massie weigh naming Jeffrey Epstein clients on the House floor

- North Carolina state senator to challenge Don Davis in toss-up district

- Massie channels Ron Paul in intraparty battle with Trump

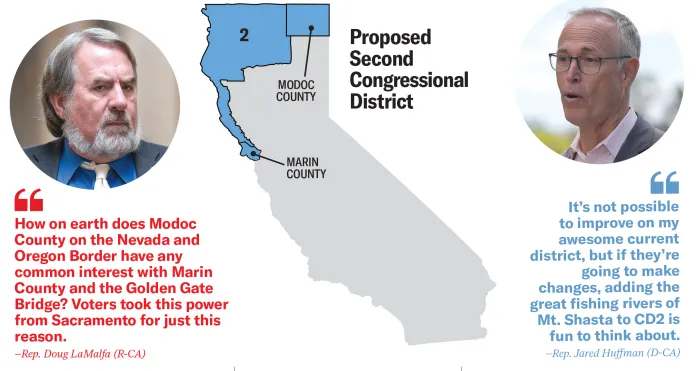

Yet, under a national House redistricting saga started in Texas by state Republicans under orders from the Trump White House, the politically disparate California counties could end up in the same, sprawling district, even though Marin’s seat, San Rafael, is 354 miles from its Modoc counterpart, Alturas.

If California voters approve the map in a Nov. 4 special election, representation of Alturas and the surrounding, deeply red parts of the state will likely shift away from Rep. Doug LaMalfa (R-CA), a low-key ally of House Republican leadership, and to the left, toward Rep. Jared Huffman (D-CA), a stalwart progressive.

Beyond distance, the counties are light-years away culturally and economically. This difference would be reflected in a shift of representation from LaMalfa, chairman of the House Agriculture Subcommittee on Forestry and Horticulture, to Huffman, the House Natural Resources Committee’s top Democratic member. If Democrats win the House majority in 2026, Huffman would be in line to chair the committee, with jurisdiction over issues related to U.S. public lands and natural resource policy. LaMalfa is also a member of the majority Republican side of the House Natural Resources Committee.

Marin is a favorite of high-net-worth Bay Area residents seeking more space than San Francisco usually provides, even though its toniest neighborhoods are home to multimillionaire tech executives, former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA), and other well-heeled families and individuals.

The county is filled with airy upscale restaurants and boutiques. It’s also home to Gov. Gavin Newsom (D-CA), a wealthy owner of wine shops and Napa Valley vineyards and the former mayor of San Francisco who now lives with his family in the county’s town of Kentfield. Newsom, driven by California Highway Patrol officers, effectively commutes to the state capital of Sacramento, 88 miles northeast.

Marin’s median family income of $120,030, according to Census data, is the highest of any California county. Politically, the county, with a population of nearly 257,000, is firmly planted on the Left. In 2024, the Democratic nominee, former Vice President Kamala Harris, won 81% of the Marin vote, with Trump winning 17%, making for Harris’s best county showing in California.

At the other end of the putative 2nd Congressional District, in heavily forested Modoc, the median family income is $46,536, the third lowest in the state. Modoc, with a population of just under 9,400 people, gave Trump 72% of its vote in 2024. This is compared to 25% for Harris in Modoc, where California’s northeast corner converges with the Oregon and Nevada state lines. Trump only did better in 33,000-person Lassen County, which is directly south along the Nevada state line, beating Harris there 76% to 22%.

The proposed new district is part of a potentially scrambled House map affecting the contours of California’s 52 seats, the nation’s largest, with Texas’s 38 a distant second. The attempted redraw is moving forward because California’s Democrat-dominated state legislature voted largely along party lines on Aug. 21 to put a constitutional amendment before voters that would ask them to temporarily replace the state’s congressional districts, drawn by an independent commission and based on 2020 Census data. This is all in response to an effort by Texas Republicans to gerrymander their map to expand the Republicans’ current 25-13 edge to 30-8 over Democrats.

The political knife fight reflects the touch-and-go nature of House Republicans’ current majority, which will be 220-215 when several seats are filled through special elections in the coming months. In the 2026 midterm election cycle, each House seat is worth fighting for to the maximum extent since majorities are built on the smallest of legislative margins.

The California ballot measure, set for an up-or-down vote in a Nov. 4 special election, will have Golden State voters decide whether to adopt a new map for the remainder of the decade. If the new congressional map is adopted, up to five Republican-held seats could flip to Democrats, giving “Team Blue” a 48-4 advantage.

Topographically diverse district

If California voters approve the new congressional map, the proposed 2nd Congressional District, which covers parts of LaMalfa’s current House district, would change considerably. In LaMalfa’s current northeast California district, Trump beat Harris 61% to 36%. However, in the proposed new 2nd Congressional District, with three heavily Republican counties cut out, among other changes, Harris would have won 54% to 42%.

The district would be among the nation’s most altitude-shifting. It would run from sea level at the coastline, stretching from Marin to the Oregon state line, and take in 14,179-foot Mount Shasta, with its snowy peak towering over the far northern California landscape and visible for more than 100 miles in each direction. The district’s disparate parts would be connected largely by two-lane highways cutting through steep slopes of places such as the Modoc National Forest, where nervous drivers must beware of a lack of guardrails.

The redrawn district would take in natural areas popular with visitors from the West and elsewhere. In Shasta County, near the geographic top of California, McArthur-Burney State Park is known for its picturesque waterfalls, with rainbows rising through the mist when the sun shines just right.

Huffman recently whimsically hinted at his enthusiasm about representing new territory.

“It’s not possible to improve on my awesome current district, but if they’re going to make changes, adding the great fishing rivers of Mt. Shasta to CD2 is fun to think about,” Huffman posted on X on July 23 in response to an imagined California congressional map redraw by Vance Ulrich, an expert in the state’s political demography.

The proposed 2nd District contours in the official, Nov. 4 special election map aren’t all the same. However, the Ulrich plan largely predicted it right, envisioning a district that would absorb all of California’s northern state line with Oregon, stretching to Nevada.

In the potentially new 2nd District, politically opposite Marin and Modoc counties would be lumped together for the first time since the Gilded Age.

“California’s most recent Congressional district to include both Modoc and Marin was the 1891-drawn District 1,” Alex Vassar, communications manager for the California State Library, wrote in an Aug. 15 X post.

Back then, California had enough population (a bit over 1.2 million people) to support six House seats. So, a single district across California’s entire upper tier and northern coastline made some sense.

Under the new map for the 2026 elections and beyond, Huffman would represent in the House parts of California’s “Great Red North,” a bloc of 13 counties that have heavily backed Trump in the past three presidential elections. However, the bloc’s electoral clout is limited, as it makes up more than a fifth of the state’s land mass but only 3% of its population.

The area is a vast, rural, mountainous tract of forests with a political ethos that resembles Texas more than Los Angeles, San Francisco, the state capital of Sacramento, and other liberal Democratic environs.

The population is shrinking, and the region has struggled economically. This was clear in Alturas in late July. The local Rite Aid was getting ready to shut down, with barren shelves and 75% off all items, while commerce elsewhere in the town of less than 3,000 people wasn’t exactly bustling.

In addition to a healthy contingent of federal firefighters, federal workers from the departments of agriculture, the interior, and others have a strong presence in the town, which has a lone blinking stop-and-go traffic light and no parking meters. The locals are partial to cowboy hats and other attire that would blend into the sartorial landscape in (relatively) nearby rural Nevada and Oregon.

Democratic politicians aren’t exactly warmly embraced in these parts. In late July, along Route 139 in Modoc, a “Farmers For Trump” sign stood prominently on a gate of Huffman Ranch (presumably with no relation to the area’s potentially next Democratic congressional representative).

“Heritage Dexter Beef and Milk Cows, Nubian Boar Goats, homegrown fruit and vegetables by God’s grace,” is the Huffman Ranch motto, according to its Facebook page. Several members of the longtime family-owned business, in impromptu conversations, disparaged California’s governor as “Gruesome Newsom.”

They said California’s strict regulations on the environment, gun control, and hunting impinge on a rural lifestyle, which urban politicians do not understand. Additionally, they said the state’s stringent air quality and climate change regulations may be appropriate for technology workers and Hollywood entertainment types, but they are onerous for people living in rural areas.

Ideological change in congressional representation?

LaMalfa has blasted the proposed new district in and around the area he has long represented. The fourth-generation rice farmer’s political career began in 2002 with an election to the state Assembly. In 2010, he won a state Senate seat and then went to Congress two years later.

“If you want to know what’s wrong with these maps – just take a look at them,” LaMalfa wrote in an Aug. 15 X post. “How on earth does Modoc County on the Nevada and Oregon Border have any common interest with Marin County and the Golden Gate Bridge? Voters took this power from Sacramento for just this reason.”

LaMalfa, 65, maintains an active Facebook presence. His everyday language touting his constituent meetings around the district, and lack of legislative jargon, suggest he writes posts himself rather than relying on his congressional press staff. LaMalfa doesn’t have many cable television hits, but he did win a measure of national fame in March 2024. After former President Joe Biden delivered what would be his final State of the Union speech, the pair had an impromptu but extended chat on the House floor about policy around U.S. Forest Service permits for harvesting timber.

More recently, LaMalfa made headlines for hosting a town hall in Chico that quickly devolved into a 90-minute shouting session. A crowd of more than 650 people at the local Elks Lodge slammed him for his vote on Trump’s sweeping agenda law, dubbed by the president and congressional Republicans the “one big, beautiful bill.” They said it would hurt vulnerable Californians and “devastate” rural hospitals.

LaMalfa tried to defend his record and that of congressional Republicans, but was repeatedly met with a chorus of boos.

If Huffman, first elected to the House in 2012, were to assume some of the new conservative territory, it would be a shift in constituency of sorts for the former University of California, Santa Barbara volleyball player (a three-time NCAA All-American) turned lawyer. Huffman, 61, has been an advocate of strong climate change and environmental protection policies since his state Assembly tenure from 2006 to 2012, and was a member of the Marin Municipal Water District for a dozen years before that.

Huffman’s public profile also contrasts with the overt religiosity of many House colleagues in both parties, which they often flaunt or exaggerate publicly for political purposes. In 2017, Huffman gave a nuanced, principled explanation of his self-description as a humanist, or non-theist.

“I suppose you could say I don’t believe in God. The only reason I hesitate is — unlike some humanists, I’m not completely closing the door to spiritual possibilities,” Huffman said in a Washington Post interview. “We all know people who have had experiences they believe are divine … and I’m open to something like that happening.”

Huffman helped found the congressional Free Thought Caucus, which aims to include “public policy formed on the basis of reason, science and moral values,” and promote “secular character of our government by adhering to the strict constitutional principle of the separation of church and state.”

Perpetual political trench warfare

Besides LaMalfa, endangered GOP incumbents include Rep. Kevin Kiley (R-CA). His current district, spanning the northeastern Sacramento suburbs and Lake Tahoe, runs hundreds of miles south to Death Valley. In 2024, voters in the district backed Trump over Harris 50.3% to 46.5%. Under the proposed redraw, Kiley’s district would lose conservative-leaning areas along the Nevada state line and pick up some of Sacramento, a Democratic stronghold, moving from Trump +4 to Harris +10.

In the agricultural Central Valley, the current seat held by Rep. David Valadao (R-CA) would be shorn of some GOP-leaning precincts. The district, currently encompassing the Southern Central Valley and eastern Bakersfield area, is slated to be pushed north, in a Democratic attempt at shifting it from Trump +6 to Trump +1. However, Valadao has a strong local following, and this new seat would be the most politically tenuous among those Democrats are aiming to flip.

A surer thing is Democratic efforts, if voters back their redistricting plan, to erase the inland Southern California seat held by Rep. Ken Calvert (R-CA) in various forms since he was first elected in 1992. Calvert’s current district, spanning the southern Riverside suburbs to Palm Springs, was Trump +6 in 2024. Parts of it would be carved up and grafted onto surrounding Democratic-leaning districts, and a significant portion would be added to a new Latino-majority seat in central Los Angeles County, basically leaving Calvert with a viable district from which to seek reelection.

Another Democratic target is Rep. Darrell Issa (R-CA), whose current district, covering Southern Riverside County and inland San Diego County, supported Trump over Harris in 2024 by about 56% to 41%. The proposed new map would parcel out many of its reddest precincts to San Diego-area districts represented by Reps. Sara Jacobs (D-CA) and Scott Peters (D-CA). The plan would also push Issa, a longtime House Democratic nemesis, north into liberal Palm Springs, with the effect of flipping the seat from Trump +15 to Harris +3.

The proposed map would also shore up several potentially vulnerable Democratic incumbents, including Reps. Adam Gray (D-CA), Josh Harder (D-CA), Dave Min (D-CA), Derek Tran (D-CA), and George Whitesides (D-CA), which would save the party millions of dollars in costly reelection fights.

SUPREME COURT LIKELY SEALED ABREGO GARCIA’S DEPORTATION FATE, EXPERTS SAY

Not that redistricting fights would end there. The Trump White House is leaning on Republican-led states to squeeze out incumbent Democratic House members through new maps, including Indiana and Missouri.

Democrats have limited options to fight back ahead of the 2026 midterm elections since several other blue states currently use some sort of independent commission to draw congressional lines. This fight will likely spill into the 2028 election cycle and beyond — in other words, perpetual political trench warfare.