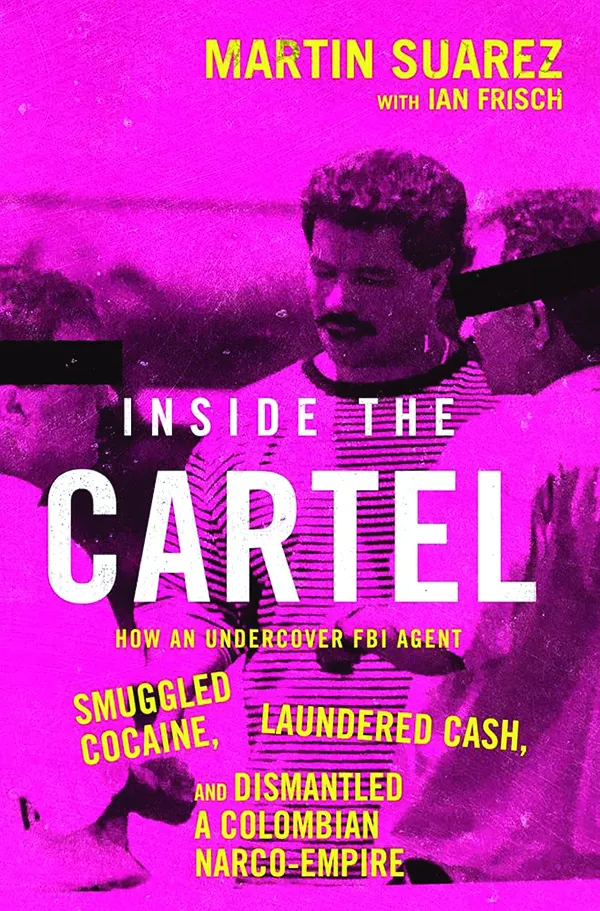

Martin Suarez opens his dramatic account of his life as an undercover FBI special agent assigned to infiltrate Colombian drug cartels from 1988 to 1994, Inside the Cartel: How An Undercover FBI Agent Smuggled Cocaine, Laundered Cash and Dismantled a Colombian Narco Empire, with the August 1994 attempt on his life. “The assassin pointed his gun at the back of my head,” Suarez writes in a gripping passage recounting how, after a morning run through his neighborhood by the Caribbean Sea near San Juan, Puerto Rico, he returned home, opened his front gate, and sat on a chair on his patio. He closed his eyes, and the hitman, called a sicario, came out of the bushes. Suarez did not see him, but he heard the sicario hiss, “Tsst, tsst, tsst.”

Recommended Stories

As Suarez notes in the book, he was the first FBI agent in history to spearhead a long-term, deep-undercover operation targeting Colombia’s most ruthless drug cartels. Rising to power in the 1980s, Pablo Escobar and his Colombian Medellín Cartel became notorious for drug trafficking, corruption, brutal murder, and ruining the lives of habitual drug users. The FBI wanted to infiltrate the cartels to learn their methodologies and internal structures, as well as thwart the flow of drugs from the source.

“That’s where I came in,” Suarez writes. “After the FBI created an airtight alter ego — what we call a ‘legend’ — I was no longer Martin Suarez. I became ‘Manny,’ a guy who had no qualms helping Colombian cartels transport hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of cocaine into the United States, all of which would eventually be seized.”

Suarez began smuggling cocaine into Florida for Colombia’s drug cartels with help from “Diego,” an FBI informant. Diego was a former pilot for Jose Gacha, who led the Medellín Cartel with the Ochoa brothers and Escobar. Diego introduced Suarez to cartel bosses as a major drug trafficker. Suarez had radios and satellite phones, which he used to communicate with the Medellín Cartel. The FBI installed hidden cameras and microphones into the equipment that recorded all of his conversations with the cartel representatives.

While undercover, Suarez dealt with a variety of criminal types, including three beautiful women who brought him boxes filled with cash from Tigre Valencia.

“Everyone called him El Viejo, ‘the Old Man.’ He was one of Colombia’s largest manufacturers and exporters of cocaine, and one of Escobar’s right-hand men. He held complete control over the rural jungles in southern Colombia near the Peruvian border, where he established massive cocaine-processing laboratories and secured an alliance with the Marxist-Leninist guerrilla group the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC),” Suarez writes.

By 1991, Suarez had smuggled millions of dollars’ worth of cocaine. He notes that he and his FBI support team gathered more intelligence, seized more drugs, and started the process of indicting more criminal targets than had ever been done before.

In 1992, the IRS received a tip from a bank in San Juan. The bank reported that a suspicious man was trading large amounts of cash for cashier’s checks, known as “smurfing” in narcotics circles. As Suarez explains, smurfing was a practice that began in response to the Bank Secrecy Act of 1970, which required financial institutions to file reports for currency transactions above $10,000. The “smurfs” always obtained cashier’s checks for under that amount, which normally kept their true intentions concealed. The IRS asked the FBI to investigate, and the agents discovered a secret money-laundering ring.

The FBI then created Suarez’s money-laundering “legend,” the backstory that would support his entry into money laundering for the cartel. Suarez posed as a highly successful smuggler with nearly 20 years of experience who now wanted to move into a less physically demanding line of work.

El Toro Negro, the name of the man Suarez dealt with over the phone, was the mastermind of this international criminal ring. He lived in Maicao, the money-laundering capital of Colombia. The city is situated on the edge of the Gulf of Venezuela on the country’s northern coast, strategically located near many offshore banking jurisdictions that had become havens for drug cartels: Aruba, Curaçao, the British Virgin Islands, and Panama.

Another of Suarez’s money-laundering clients was the North Coast Cartel, led by Alberto Orlandez-Gamboa, also known as El Caracol, a reference to a famous Colombian beach with the same name. Although the name technically means “the shell,” his nickname was translated into “the Snail.”

“I had been so used to the world of smuggling — flashing cash and making a scene at the fanciest restaurants — that I quickly realized that money launderers were a different breed. It’s a complicated business, one that requires a financier’s knowledge of the banking system, a spy’s handling of covert meetings, and a criminal’s ruthless disregard for the law. Most of these dudes were highly educated. In fact, the Cali Cartel’s money launderer, Franklin Jurado, studied economics at Harvard. They didn’t need to flash their money. They just needed to not get arrested,” Suarez writes.

In August 1994, the FBI called the undercover investigation complete. The U.S. Attorney for the District of Puerto Rico filed the indictment in federal court. Fifty-two members of the cartel and their associates were charged with crimes, ranging from money laundering to drug trafficking. Nearly all of the defendants pleaded guilty, including several who became cooperating witnesses.

TRUMP SAYS US IN ‘ARMED CONFLICT’ WITH DRUG CARTELS IN MEMO TO CONGRESS

After surviving several dangerous situations undercover with bravery and resourcefulness, including fighting off a sicario attempting to murder him, Saurez retired from the FBI in 2011.

Inside the Cartel is a well-written and suspenseful book that illuminates the dark and dangerous world of narcotic traffickers and reads like a thriller.

Paul Davis is a writer who covers crime, espionage, and terrorism.